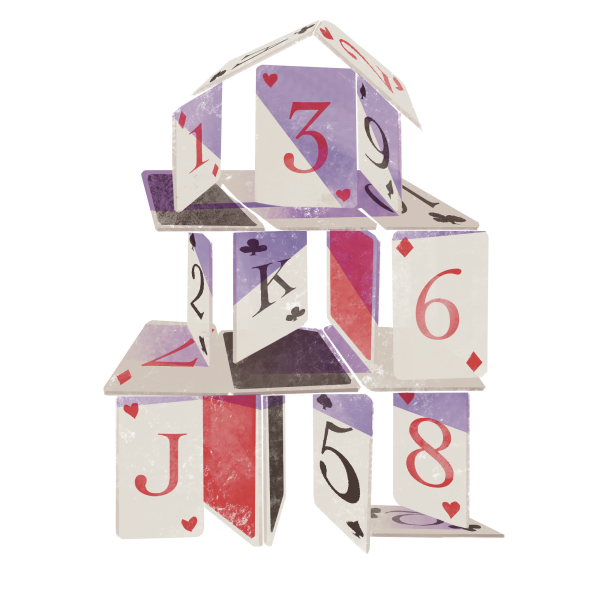

The difference between reality and the media’s make believe for teens

In the pilot episode of Britain’s acclaimed TV series “Skins”, heralded for its frank and human depiction of teenagers, members of the ensemble cast get drunk, pass out on pills, smoke marijuana and try to get an anorexic girl to have sex with the only virgin in the group. Despite this drastic behavior, later on in the season, two friends clash over one’s homosexuality, clarinet recitals are practiced for and parents are a constant letdown, all starkly contrasting the outlandish activities above and grounding the series into a haunting, depressing reality.

Is this an accurate portrayal of teenage life?

“Skins” is only the tip of the iceberg of risque Western teen entertainment. From Harmony Korine’s NC-17 rated movie “Kids” (1995), portraying underage adolescents having random unprotected sex during the AIDS scare in New York City, to the homage to our hometown “Palo Alto” (2013), there is a slim chance for teenagers to be portrayed as anything other than the derisive, stoned, lost, angsty wild cards we all know, love and are — right? We all enjoy the perks of carefree drug use, sexual activity and parents who let their kids freely smoke cigarettes at the dining table.

Except not.

There are plenty of high schoolers in Palo Alto who choose to spend their time at band practice and the well-worn wood of their desks rather than indulging in contraband and lack of common sense. Cigarette smoking is only performed by the Center for Disease Control’s 14 percent of teenagers in the United States in 2012. There is also no question that there are teenagers out there that engage in this sort of Friday night fun. But is the real thing to the extent that we see on many outlets of teen media? There’s no barrier to what is broadcast onto screens, but should controversy for the sake of ratings extend to depictions of teenagers?

One sampling of teen media to look at to help answer these questions is the film “Palo Alto,” a chronicle of the hyped-on-drugs-and-angst teenagers that make up James Franco’s 2010 book, also titled “Palo Alto.” The movie and book cover the varied misfortunes afflicting the teens of Franco’s high school era Palo Alto — a world of slowly evolving vices, quietly moving scenes and, in the novel, an indulgence in just about everything illegal. The movie features teenage bad behavior in all of its glory: Emily (Zoe Levin) gives out sexual favors, April (Emma Roberts) covets her soccer coach Mr. B (James Franco) and the lost boy Teddy (Jack Kilmer) commits a “hit and run” after binge drinking at a party. “Palo Alto” is a little different from the world of “Skins” and other foreign real life teenage dystopias — the kids that binge on alcohol and drive around in intoxicated stupors do so in our town, at places that we recognize such as Jordan Middle School, Palo Alto High School, Mitchell Park and other Palo Alto landmarks. The wandering, uncertain lives of these high schoolers is meant to reflect James Franco’s feelings about his time in the realm of adolescence.

“When I was in high school, I had friends and I had some good experiences, but I was also very confused,” Franco said in a series of interviews he conducted with the cast and crew of Palo Alto for V Magazine. “And I was kind of lonely a lot. There were some really sad things in all of that, and so at the time I think I probably wasn’t that happy, but going back and writing about it, even though I was writing about some hard experiences, it was actually really enjoyable.”

So Franco speaks from his heart. But still, both “Skins” and “Palo Alto” open up a debate about the quality of the media for teens out there. Is portraying teenagers engaging in illegal and dangerous activity an accurate portrayal of the trials and tribulations youth must go through with the angst of adolescence, or is it an over-exaggerated statement that may convince teenagers of standards of misbehaving that do not exist? James Franco’s work is from his own experiences, according to him, and he is allowed to write and create his own interpretation of high school life. Many of his characters go through heart-wrenching incidents and meet unbeatable obstacles.

While most teenage media, including “Palo Alto” and “Skins,” is considered artistic expression and not real life documentation, there are several studies out there that suggest media is affecting the way teens operate with themselves and their peers. The University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill conducted a five year project from 2001 to 2005 which, according to their website, “examined the effects of a range of media on adolescents’ sexual health.” In total, ten different studies were published from the project by professors and researchers. While the findings were mainly focused on seventh and eighth graders, they offered a legitimate look at the effects of the media on teenage minds, especially concerning their sexuality. One study, entitled “The mass media are an important context for adolescents’ sexual behavior,” shows that teenagers’ sexual tendencies are swayed by what is portrayed in the media. One statistic offered in the paper said that out of the top 20 Nielsen-rated teen television shows, 83 percent contained some degree of sexual content. Compared with that, only 12 percent of said televised sexual content discussed sexual risk-taking and subsequent responsibility. The study also showed that “media variables added two percent to the prediction of intentions to have sexual intercourse in the near future.”

These studies show how the world of teen media creates a strange mirror for its target demographic: it is like looking into your reflection and seeing a corrupted version of yourself. And alas, there is more evidence to show that even beyond the scope of teen media, teenagers greatly misperceive the illicit activities of their peers.

A study published by researchers from UNC Chapel Hill, Stanford University, Tilburg University in the Netherlands and other institutions in Dec. 2014 suggests that adolescents overestimate the amount of sex, drugs and alcohol their peers engage in. As written in Stanford News, the experiment utilized 235 sophomores at a suburban high school for studying five social sub groups: the “popular” kids, “jocks,” “burnouts”, “brainiacs” and lastly, students who were not part of a single group. The team of researchers had each group report on their own activities regarding sexual activity, alcohol consumption and cigarette usage, among other related engagements. The results yielded some very surprising results. Each group estimated numbers that were way above the actual figures — for example, jocks reported that they almost never smoked, but other groups thought that the jocks smoked at least one cigarette a day. Jocks also garnered higher numbers regarding interactions with sex and alcohol. On the other end of the spectrum, brainiacs studied much less than their peers thought. In fact, the self-reported statistics (the information that each group disclosed for themselves) did not differ from group to group. The distinction came with groups reporting on other groups.

Dr. Geoffrey Cohen, a researcher and professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Education, elaborated on why these discrepancies exist.

“[Exaggerating risky behavior] just has more social currency,” Cohen said. “It’s easy… [People will absorb what is] available and salient.”

Cohen also mentions the availability heuristic, a psychological reaction that causes decisions to be made based on immediate recollections of past examples. Because these examples arise, people are inclined to believe that they reflect what may happen often or in the future. However, Cohen does emphasis that the exact cause of these misunderstandings is unclear.

“Where does the bias come from?” Cohen said. “We need more research on that.”

The concept of the availability heuristic suggests that teenagers may be recalling past examples of what they have seen on television or in the movies when trying to make decisions in real life. Perhaps teenagers are filling that uncertainty with what is influencing the environment around them.

Overall, as is obvious in this digital age, media is the collective wisdom of the times — it wields more power and influence than any other thing in our society. We cannot hope to connect with everyone in our peer groups. As Dr. Cohen adds, the fast paced lives of teenagers and tendency to not disclose information may cause misunderstandings even between good friends.

“It makes it really hard to know the truth about what is true in people’s hearts and minds,” said Dr. Cohen.

Media fills the gap in lieu of truth. If one is not aware of what his or her peers are thinking, then the media becomes the easiest thing to grasp. When faced with ambivalences, teenagers can latch onto true or untrue information. And while artists and writers like Franco have every right to publish their material, the effects of their creations may not be so positive.

The truth is, real teenage life should not be measured against the false representations of movies, television and other media. Do not be fooled by what the media tells you about what is acceptable and what is not. Live your adolescent life by your standards and make choices that you deem fit. As Franco would have wanted, create an interpretation of the world that is true to your own experiences, not anybody else’s.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Palo Alto High School's newspaper