American baseball needs to be refreshed

Japan’s baseball has what America’s doesn’t—an intensity that appeals to the younger generation

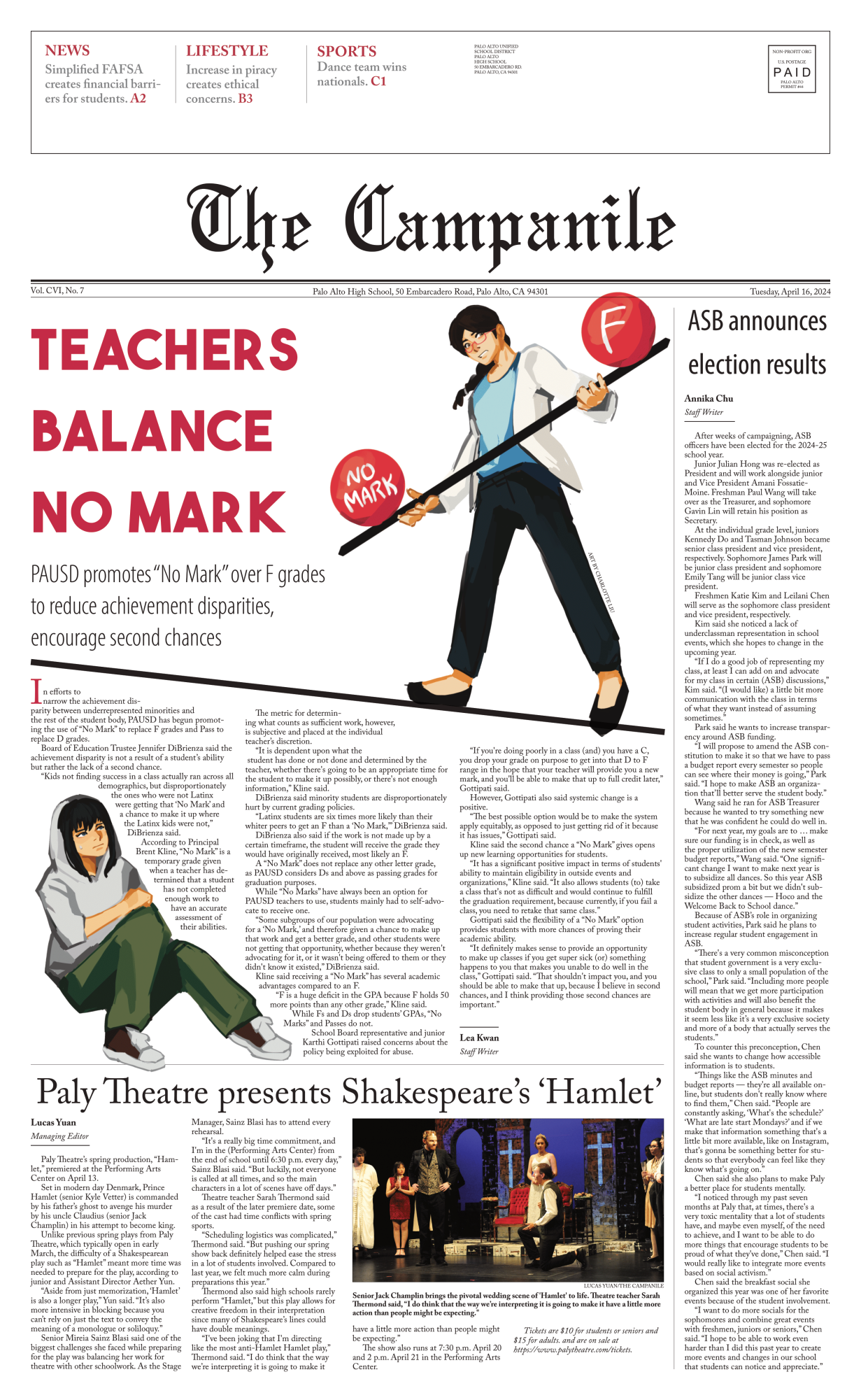

Courtesy of nytimes.com

Matt Murton, an outfielder for the Hanshin Tigers, makes his 211th hit of the 2010 season, breaks the Japanese single-hit record.

Baseball is in crisis. Now, this is not meant to be some sort of fear-mongering, paranoiac, McCarthyistic rant on the decline of American values. It’s just the truth. It might not be obvious in a Bay Area that has enjoyed an enormous amount of success in the last five years, but people just do not care anymore. Minor league membership is down by around 17 percent and the majority of spectators consist of middle-aged white males — not a dynamic, vibrant audience by any stretch of the imagination (no offense). So what do we do? Is baseball not the national sport of liberty? Is it not all Fourth of July barbecues? When freedom rings, does it not just ring from the mighty mountains of New York, but from Yankee Stadium in the Bronx? Does it not just ring from the curvaceous slopes of California, but from AT&T Park in San Francisco and Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles? If it does, then why don’t people care anymore? And more importantly: how do we make people care again? Well, a solution is necessary, and it might come from a rather unlikely source: Japan.

It’s hard to know where to begin when discussing what baseball means to Japan, but how about this: Japanese baseball is more American than the Major League Baseball (MLB). In Japan, games can only last a maximum twelve innings. Does that not just scream America? The nation that invented the 24 second shot clock to hurry things up basketball? But it’s Japan that has a time limit in its baseball games, whereas in the U.S., baseball games go on until they finish, which can go on for hours. By limiting the time a game takes, long tedious at-bats where a player will readjust their gloves ten times are avoided. Although there has been some experimentation with timing in the Arizona Fall League, it is still a long way off from being implemented in the MLB.

There is a question of the intensity, and in Japan, it seems there is nothing quite like baseball. Each game is packed to the rafters and the cheering rings around the stadium in an ever-increasing hurricane of noise until it reaches an earth shattering crescendo, at which point it stays at this fever pitch until the end of the game. There is no respite, there is no relief, just an almost primitive, basic carnal passion.

The fans’ enthusiasm is even more impressive when you take into consideration the mentality of the general public with regards to the MLB. Many Japanese baseball players view the MLB as the holy grail, a nirvana towards which they should work for, and there is a general consensus that the MLB is ultimately the best baseball league in the world.

Despite acknowledging the superiority of the American game and dreaming of making it all the way to the majors, fans still regularly go to see their local teams as opposed to just staying at home and watching the MLB. For example, the Yomiuri Giants drew upwards of 3 million in attendance last year. The Giants’ San Francisco namesake, in their world series-winning season drew about 350,000 more people in attendance than Yomiuri. However, San Francisco also played 22 more games than the Tokyo team. The Yomiuri Giants had a 42,000 average attendance, meaning that if they had played those extra 22 more games, the Yomiuri Giants would have outstripped the Bay Area ‘world-beaters’ by about 550,000 in attendance figures.

This contrasts sharply with the American view of baseball, where baseball represents a relaxed aspect of the American psyche. Let me explain.

Society can basically be divided into two frames of mind: anger and peace. Where one side is hyper-aggressive, angry and frustrated while the other is a relaxed, prospering and content society happy with life. Now, these moods need to find some outlet through which they can be expressed, and typically in the U.S. this can come in the form of sports. For example, football could be considered an outlet for all the pent up rage and frustration we accumulate throughout our week. Baseball provides the exact opposite: A golden sun dipping down under the crisp, sea-lined horizon as the Giants play whoever, with your loved ones around you and hot dog in hand, baseball is the perfect expression of contentment and happiness.

In Japan, baseball represents something else, where all of the frustration and anger going into football in the U.S. goes into baseball instead. In practice, players will work themselves to the point of complete physical exhaustion, something that could be interpreted as a release for any pent up fury. Every time a player crushes a ball off for a home run, or the opposing player makes some grotesque error, fans delight.

So now, let’s get back to the question at hand: what can the U.S., or more specifically, the MLB, learn from Japan to get its baseball back on track? Well, for starters, you have to be relevant, and fifty-something year-old audiences aren’t going to make you relevant. Baseball needs to start by rebranding itself not as a relaxed picnic, but an intense experience. Why? Well, if you recall, baseball was an expression of our relaxed, calm, nowhere-to-go-and-nothing-to-do-attitude. The problem? That’s something out of the fifties. The MLB is still considering itself the sport for a time of prosperity, for people who had all the time in the world and very few worries, a bit like the eighties and nineties that saw baseball’s reemergence (partly due to steroids). This new generation of sexually repressed, frustrated and impatient tech-kids has no interest in that lifestyle, it has no time for relaxing and just watching a baseball game.

The MLB can only regain popularity by mimicking Japan’s intense atmosphere, where baseball can take on the role of the cathartic sport. There is, of course, the alternate view that if baseball can just hold out for a return to a relatively functional society where people relax, it will return to its halcyon days… It could, but then again, I’m writing this in front of a screen at 2 a.m. on a Saturday night, a screen that pretty much holds everything I need to know. Including friends in their respective rooms, with their respective screens, friends with whom I can communicate at any time of day without meeting up. So remind me again: why do I need to go to a baseball game?

Your donation will support the student journalists of Palo Alto High School's newspaper