Your donation will support the student journalists of Palo Alto High School's newspaper

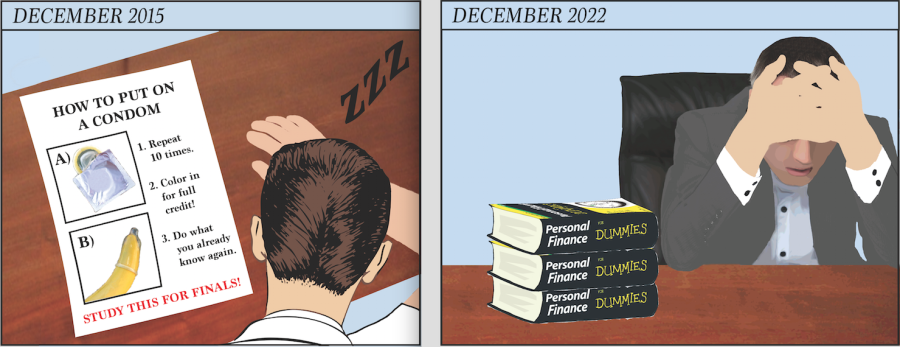

Repeating skills that students have already learned in Living Skills is not beneficial to graduates.

Personal finance should be integrated into course curriculum

October 30, 2015

Palo Alto High School does not have a single course that provides its students with personal finance education, despite the interest that students have in this area. A recent study by Sallie Mae, a consumer banking company, found that 84 percent of high schoolers have an interest to learn more about personal finance.

To graduate from high school in California, students must take required classes in core subjects and language or visual arts. However, financial literacy is never taken into account and students are heading off to college with little formal education on balancing checkbooks, keeping a good credit score or taking out student loans.

As a result of apathy on the part of the state, there are many free online resources for both educators and students online. Tim Ranzetta founded NextGen Personal Finance (NGPF), which provides interactive financial resources, after volunteering to teach a course in personal finance at Eastside College Preparatory School.

“A lot of products are changing,” Ranzetta said. “I wanted to engage students, and teach them to be lifelong learners. Too much of personal finance curriculum that I saw was based off of definitions. Ultimately it is the decisions that matter, that’s all personal finance is, making strong decisions.

The state of California recently received an “F” from Champlain College’s Center for Financial Literacy for failing to require districts to provide students with the tools for financial success. California recommends a ninth-grade elective course in personal finance be offered, but local districts are not required to offer such a course. As a result, it is often underlooked, even if educators recognize it is an important subject.

“I think financial literacy is essential,” Santa Clara County superintendent Jon R. Gundry said. “Local school districts should make the decision whether it is a graduation requirement, but it should be included in everyone’s academic program.”

Yet, Palo Alto High School is among the schools that do not provide such courses, instead providing students with a class called Living Skills, which is mandatory for graduation. According to the course catalog, Living Skills’ main purpose is to inform students on making personal health decisions, forming interpersonal relationships, managing life crises and cultivating “democratic values and behavior appropriate for a responsible community member.”

While these are important skills to have, students are not satisfied with the level of education they receive from the class, often finding that Living Skills spends too much time repeating information that students already know and not enough time covering equally important topics such as filing taxes.

“Living skills is supposed to make you ready for adulthood, but it doesn’t teach you how to get apply for a credit card, or how much living will cost in the future,” senior Ren Makino said.

Although integrating personal finance into Living Skills is one option, the school district could also opt to create a pilot standalone finance class. By creating a pilot, the school can gauge student response and test out the curriculum before distributing it to the existing courses.

School is about giving students tools to succeed in the future, and the motivation to learn about personal finance exists. Even at home, many parents shy away from such discussions. Money is among the lowest priorities in conversations between parents and their children — below talks about the importance of good manners and the benefits of good eating habits, according to a survey by Harris Interactive released in August.

“The missing piece is not only from an student education standpoint, but also from the need for parent education,” said Ranzetta. “Students learn most of their lessons from their households, so it is also important to educate parents, so that generational learning can take place.”

Integrating personal finance coursework into the existing curriculum is not without challenges. Teachers will have to receive additional training, which will be an added expense, and in the end, educators may still not feel comfortable teaching the new material.

Carroll County in Maryland chose to implement a standalone financial literacy course, independent of state education requirements. The total cost for training teachers and buying resources for the students, in all eight of its high schools, totaled just $37,700. However, incorrectly teaching financial literacy can have major impacts on student wellbeing.

In a study by the University of Wisconsin — Madison, 64 percent of Wisconsin educators said they felt underqualified to teach the state’s financial literacy curriculum and very few felt comfortable teaching a class on subjects such as risk management.

“Too often teachers don’t feel they have enough professional development time, because this is an area that is constantly changing,” Ranzetta said. “Experts disagree on many areas, so it is important to be comfortable with ambiguity. I don’t want to teach kids what the right answer is, I want to teach them how to find the right answer.”

Ultimately, the burden of integrating financial literacy lies with the administration, even if the true damage is done on the students themselves.