It is two o’clock Monday morning and there is still calculus homework to do and an Advanced Placement U.S. History chapter to read. The SAT is on Saturday, and finals are the week after.

This type of situation is what students deem as stressful, an insight into many people’s myopic perception of stress and its effects. We place a stigma on stress, and while this caliber of stress is evidently detrimental to health, certain types of stress can actually be beneficial.

In a psychological context, stress is defined by endocrinologist Hans Selye as three “essentially dissimilar” concepts: a stimulus, a response to a stimulus or the physical effects of the response. And under the vague umbrella of stress, the response to an uncontrollable stressor, exists two branches: eustress and distress, in other words, good stress and bad stress.

When students typically think of stress, they think of distress: frustration, high tension, depression and anxiety. Many students face considerable distress in their academic lives from having to manage school and extracurriculars while still somehow finding time for a social life—a tour de force by any standard.

And in response to this overwhelming stressor students call academia, the physiological and psychological systems react negatively to the stressors in an attempt to cope with the stress.

When people are distressed, they become forgetful, feel nervous and experience dozens of other psychological and physical effects. While these effects seem transitory, stress does have adverse long-term effects. The irony is that ongoing stress high schoolers experience because of their grades hinders many processes.

The “fight-or-flight” response developed by Walter Cannon in the 1930s is perhaps the most widely known theory describing the autonomic nervous system’s response to stress: faster heart beat, higher blood pressure and higher glucose level.

Encountering and dealing with stressors has temporary effects, but repeated exposure causes bodies to adapt and continue acting as if there were a stressor present. Long-term stress adversely affects both the psychological and physiological systems, changing mood, behavior, emotion as well as bodily systems. And to compensate for the distress, many people resort to detrimental coping mechanisms such as drug abuse, social isolation, procrastination, overeating or undereating, to name a few.

With the possible negative effects to physical and mental health, why do certain people believe some stress should be celebrated?

Though counterintuitive, not all forms of stress are bad. The distinction between distress and eustress depends on a person’s perception of a threat or a challenge.

According to psychologists Jim Blascovich and Joseph Tomaka, the distinction between a threat and a challenge lies in the relationship between demands and resources: when there are more resources than demands, we sense a challenge, but when there are more demands than resources, we sense a threat.

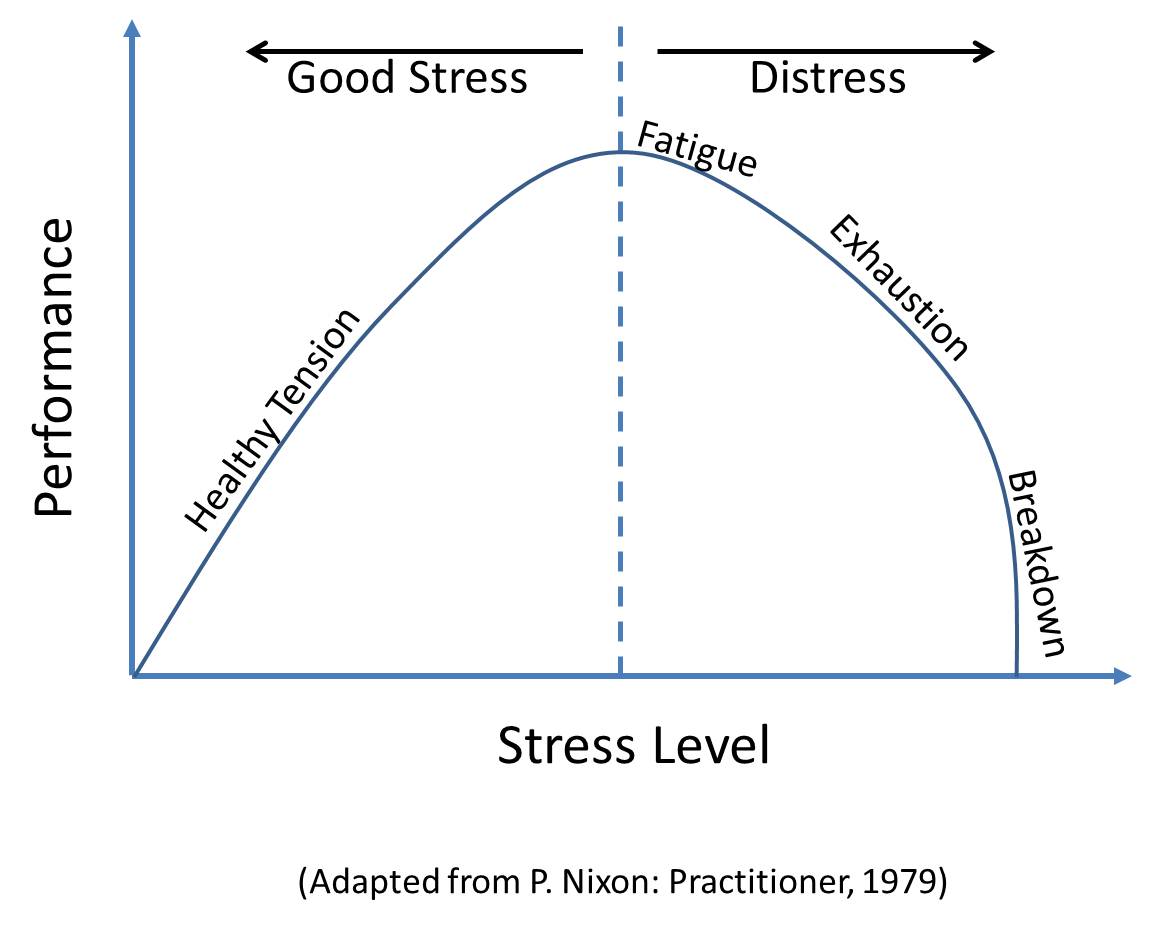

Distress, the response to a perceived threat and what students encounter most often during the academic school year is unhealthy in the long run, but eustress, the response to a challenge, is a different branch of stress. Eustress can act as an impetus, a stimulant sharpening our senses and motivating us to face a challenge or achieve a goal. In addition, eustress helps students, and other people in general, focus their energy on the challenge at hand and ultimately improve their performance. It is, as many say, a form of “healthy” stress.

Students experience eustress in many different contexts, such as when playing sports or participating in competitions in order to lend power to one’s physical self.

The former helps the mind fight irritability and depression.

Enough sleep, good grades or a social life: pick any two. To many students, this aphorism is the truth. Each student picks a different pair, and many choose enough sleep—well probably not what they should be getting—and good grades. A social life can wait. But according to co-founder of the concept of social neuroscience John Cacioppo, our social lives play a major role in the stress we have or do not have. Unhealthy or healthy relationships and even dominance and submission determines our levels of social stress, the most common form in students.

The relationship between academic relationship and stress is grey: constant stress over grades hinders our academic performance, an inverse relationship, while acute stress to face a challenge can be beneficial, a direct relationship.

Though it is possible for stress to inversely affect our GPA, this is not to say students should completely relax and just neglect their responsibilities and commitments, but rather to say students should stay reasonable and not completely overwhelm themselves.

“Stress is bad.” Well, it is not that simple. Each student has a different level of self-confidence, and each student chooses a different coping mechanism. Under the same circumstances, different people react differently. Being “stressed” is not all bad, as many think, nor is it all good. But a piece of advice: break the cycle of procrastination, get work done early and you will relieve yourself of huge amounts of distress.