The Price of Progress

As a longtime resident and former mayor of East Palo Alto, Ruben Abrica remembers when he could have bought a home in his city for just over $200,000. That was in 2009. Today, he drives through the same neighborhood, where the same house is listed for $1 million.

“Someone who’s got more money than you (is) going to replace you,” Abrica said. “This is gentrification displacement.”

East Palo Alto Mayor Antonio Lopez said to understand East Palo Alto’s gentrification, it’s first important to understand the term.

“Gentrification is the process whereby things get more expensive because folks from higher income communities come into a place that’s lower income and thereby increase the cost of living for everyone who lives there,” Lopez said.

Following World War II, many minority families began to consider Palo Alto as a region to settle.

In the past, East Palo Alto had a large African-American population, because the city’s affordability attracted African Americans after World War II, AP US History teacher Katya Villalobos said.

And former Palo Alto Mayor Patrick Burt said World War II was a catalyst for increasing diversity in East Palo Alto.

“Defense industries brought a great migration of African Americans from the South to the Bay Area, in Richmond, within San Francisco itself and in East Palo Alto,” Burt said.

However, this diversity did not last. According to the U.S. Census, the population of African Americans in East Palo Alto dropped from over 60 percent in 1980 to 15 percent in 2020.

Palo Alto and East Palo Alto have always been two separate cities, but in an attempt to bridge the gap, the 1986 Voluntary Transfer Program, more commonly known as the Tinsley program after former parent Margaret Tinsley, brings up to 135 students each year from East Palo Alto and East Menlo Park to other school districts, including PAUSD.

“The Tinsley program was the result of a desegregation lawsuit that was filed by some families in the Ravenswood School District in East Palo Alto,” Abrica said. “Ravenswood School District covers East Palo Alto and East Menlo Park.”

The lawsuit said racial differences between Palo Alto and East Palo Alto create a segregated school system. And a settlement order in San Mateo County Court in response to a petition filed by Margaret Tinsley and other parents of the Ravenswood School District sided with the plaintiffs.

“The student population of respondent Ravenswood City School District elementary schools is predominantly minority, while the student populations in the elementary schools of the other respondent school districts are predominantly white,” the petition states. “Because of the interdistrict racial imbalance in student enrollment, minority students are realistically isolated, and so a segregated school system exists.”

East Palo Alto still struggles with issues that have been around since its inception, including the annexation of some of East Palo Alto’s land for the construction of Highway 101. In order to understand East Palo Alto’s place in the Bay Area, Abrica said it is important to understand the historical differences between Palo Alto and East Palo Alto.

“The first thing to know is that Palo Alto is in Santa Clara County, and East Palo Alto is in San Mateo County, which means that they never really have been connected in the sense that the county boundaries make it very difficult to join together,” Abrica said One of the main reasons for this division was Highway 101, built in 1926. Lopez said the freeway was expanded into East Palo Alto in the 1960s, before East Palo Alto became a city in 1983.

“There were quite a few accidents in the bottleneck part of 101, where East Palo Alto is,” Lopez said. “So it was the wisdom of the state of California, in conjunction with other cities, to basically put the freeway directly in the heart of East Palo Alto’s downtown.”

The freeway divided East Palo Alto, weakening its appeal to home buyers and harming its tax base in the time before East Palo Alto was even a city. However, Lopez said the harmful effects don’t stop there.

“There’s a big sound wall, and you think of the quality of someone who’s trying to sleep in an apartment, in the Woodland Apartment, and they just hear the rush of cars constantly all day, all night,” Lopez said. “It’s going to interrupt your sleep, not to mention the exhaust, right?”

The freeway also presents challenges with connectivity within the city. Lopez said East Palo Alto residents have to cross Highway 101 almost daily.

“The folks who live on the west side have to literally go across the bridge every single day to access basic services, food pantries, permits and City Hall,” Lopez said.

Though the freeway improved connectivity throughout California, Lopez said the expansion of Highway 101 deeply hurt East Palo Alto as a city.

“The result of that in the ‘50s and ‘60s was you had businesses displaced from East Palo Alto, so the economic engine of the community was basically cut out from under its feet,” Lopez said. “It was for the sake of the wider region’s ability to have transit and to have connections between the major cities of the Bay Area, but they left us cut in half.”

Villalobos said Palo Alto’s housing was rife with redlining — preventing certain groups of people from living in certain areas — which was mainly meant to keep African Americans out of traditionally white neighborhoods.

“Redlining was reinforced by many of the banks, where they specifically were not lending money to African American families to get homes in different parts of the cities because they believed that it would lower property values,” Villalobos said.

Palo Alto residents even took redlining one step further with “blockbusting,” a practice where whites would move out once an African American family moved into the area.

But Villalobos said as more tech workers came into Silicon Valley in the 2010s, a lot of them chose to reside in East Palo Alto because of lower housing prices.

“When Facebook and all those other tech companies moved in that area, where were these people going to go,” Villalobos said. “They started to see East Palo Alto as well: It’s not as expensive as Palo Alto, and it’s closer to my job than San Jose.”

And home prices in East Palo Alto have skyrocketed. In 2010, a year an economic recession, the median home price was about $250,000 in East Palo Alto, according to realtor Juliana Lee. Since then, the median home price in East Palo Alto has surpassed $1,000,000.

In comparison, the median home price was about $1.5 million in Palo Alto in 2010. Today, the median home price is closer to $4 million. The average household income in East Palo Alto is $136,345 with a poverty rate of 12.19%, while in Palo Alto the average household income is $301,266 with a poverty rate of 4.6%.

Abrica said many early home buyers in East Palo Alto decided leave at housing prices went up because they could make a lot of money by selling.

As a result, Abrica said the process can benefit people that own their houses.

“Because the value of the properties has gone up, and that’s one of the phenomena of gentrification, then the people who bought their homes for less money now can cash in for a lot of money,” Abrica said.

With more early buyers selling their homes, Abrica said more people from outside the city are coming to East Palo Alto.

Another factor increasing gentrification is East Palo Alto is a change in community perception.

In 1992, East Palo Alto was known as the Murder Capital of the US. The homicide rate was 175 murders for every 100,000 people, while the nationwide rate was 9.3 murders for every 100,000 people — almost 20 times less.

Lopez said East Palo Alto’s infamous violence pushed down property prices.

“People move into an area for the quality of the schools and for the sense of safety,” Lopez said. “Our location has always been an asset. What countered it was this perception from folks about … the stigma around the community and how it’s been represented throughout its life.”

However, East Palo Alto’s crime rates are turning around. In 2023, the city had zero homicides. Lopez said now that crime is falling, gentrification may begin to accelerate in East Palo Alto, pushing even more people out.

“Last year we had zero homicides,” Lopez said. “So for me, that’s great—that we are a safer community. The flip side of that is that you have this enormous appreciation of property values.”

Although many people think gentrification has only affected East Palo Alto, Abrica said Palo Alto actually suffers more now from gentrification because of its lack of rent control laws.

“The renters in Palo Alto are being gentrified every single day, more than our renters,” Abrica said. “Why? Because in East Palo Alto, and I know that because I’ve been personally involved the minute I moved there, we have had rent stabilization and just cause eviction laws.”

Senior Justun Kim and junior Khrisar Magana, both Paly students who live in East Palo Alto, along with junior Adan Perez, who previously lived there, have all been part of the Tinsley program.

Kim said attending Palo Alto Unified School District offers many advantages over Ravenswood, such as access to high-quality resources like public libraries and advanced academic programs.

“East Palo Alto has so many less facilities compared to Palo Alto, and students there don’t have as many opportunities,” Kim said.

Despite living in East Palo Alto, Kim said he is grateful to be attending Paly through the Tinsley program.

“I got really lucky being able to join the PAUSD, and I feel like I fit in really nicely,” Kim said.

However, not all students have the same experience. Magana said the separation between Tinsley and non-Tinsley students is noticeable.

“We have the same opportunities, but I feel like we tend to group ourselves up a bit … there’s still that separation,” Magana said.

Though the Tinsley program was meant to help students from East Palo Alto, Abrica said it had flaws from the outset.

“The idea was that some kids from Palo Alto, from Menlo Park and from Belmont would also go to the schools in the Ravenswood school district,” Abrica said. “But nobody ever did.”

He also said when the program first started, there was a greater difference between the quality of the school districts, which, in turn, led to the rise in popularity of the Tinsley program. However, as time passes, Lopez said this mentality can be dangerous.

“I think part of the appeal of the Tinsley program is the perception that the school district is so woefully inferior to PAUSD, but the problem with that mentality is it’s sort of a self-fulfilling prophecy,” Lopez said.

In addition, Lopez said state funding for schools is a problem for Ravenswood schools. When fewer students attend high school in Ravenswood, the school does not get as much money.

“We used to have 4000 students. Now we have about 2000. A lot of that has to do with the Tinsley program,” Lopez said. “This (causes) a disparity in resources because as a result of opting your student out, the school loses funding.”

Additionally, Lopez said the Tinsley program hurts the spirit of the city because students are scattered for their education.

“Remember, East Palo Alto, at one point, did not have a high school for 20 plus years,” Lopez said. “Think about the impact that makes when you have your student body scattered in all corners of the county and of the peninsula – the lack of unity, the lack of cohesion, the lack of having a common experience – and how that then troubles the ability to organize civically, to lead, to govern, because everybody has their own story about school.”

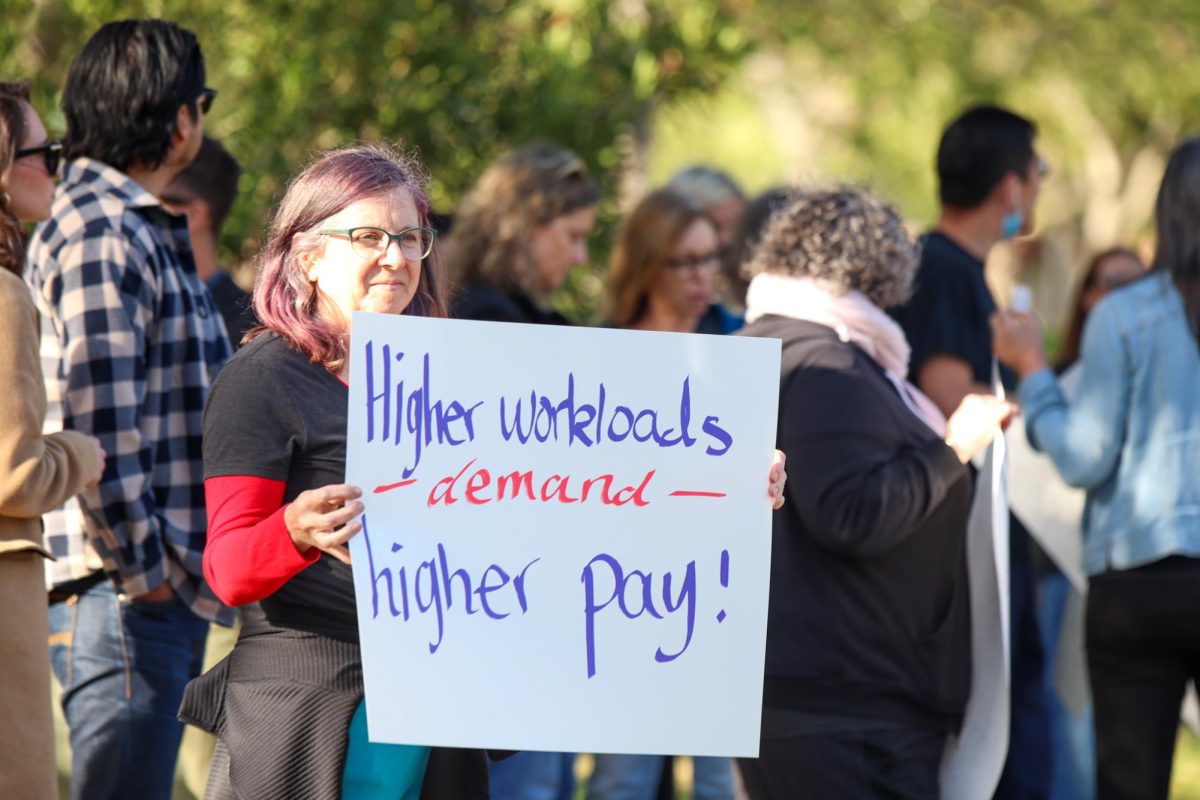

Despite East Palo Alto’s historical problems and weaker tax base due to tech companies, redlining, racism and a freeway, the city passed the 2024-2028 Affordable Housing Strategy in February, an effort to build more low-income housing to accommodate the needs of renters in East Palo Alto.

“If we’re the only ones building for this segment of the population, that’s going to hurt us,” Lopez said. “I want to emphasize, it’s not an East Palo Alto issue; it’s a regional issue. In the past 10 years, for every unit of housing that we’ve created, we’ve created nine jobs. So we have a one-to-nine housing job ratio. If other cities do not all work together to build commensurate housing on all income levels, we’re going to continue to see housing prices rise.”

In the end, Lopez said all cities need to share the blame for rising prices and unaffordable housing.

“The true root of the problem is all of our collective responsibility to make this place affordable,” Lopez said. “We, as cities, frankly, have failed.”

Additionally, Lopez said the cities involved need to revisit the Tinsley program and how it can be changed to fit today’s needs.

The Tinsley program served its purpose 40 years ago,” he said. “There needs to be revisiting and having an important conversation. What is the efficacy, what is the purpose and what is the benefit of this program in 2024? Is it an asset, or is it a liability? Is it actually moving our community forward, or is it hurting our autonomy and our ability to govern and create a sense of unity?”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Palo Alto High School's newspaper