In the midst of an increasingly contentious presidential election season, the political landscape of the United States seems to be reaching new heights of polarization. Political polarization is a term that describes the shift of the average person’s political beliefs towards the extremes. Many who employ the term also use it to refer to the increasingly fervent dedication with which citizens subscribe to their political ideologies.

As political polarization exacerbates to a degree unprecedented in American history, understanding this phenomenon has become essential to understanding U.S. political discourse. According to Pew Research Center, the overall share of Americans who express consistently conservative or consistently liberal opinions has doubled over the past two decades from 10 to 21 percent.

The implications of this statistic are significant. More and more, the political opinions of Americans are determined by their party affiliation. While many of our grandparents selected the political party which most closely aligned with their political opinions, we are beginning to select political opinions which most closely align with our political parties.

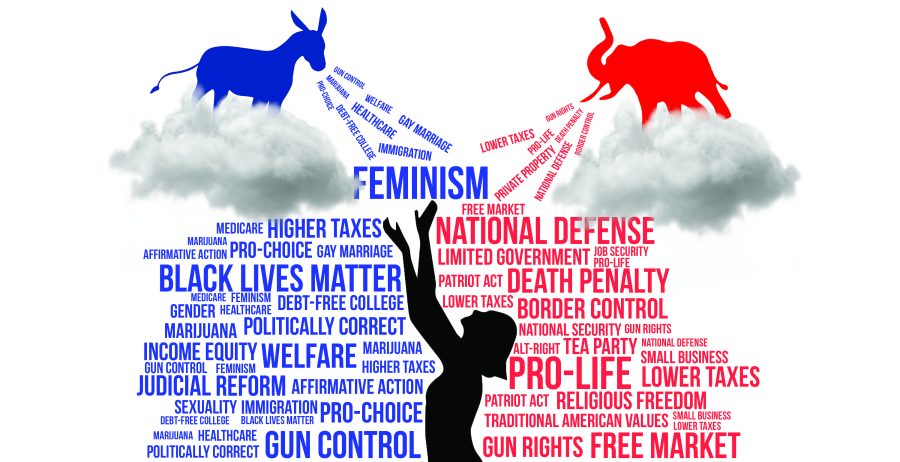

Consider, for example, your views on addressing climate change. Now, think about your views on gun control. Almost everyone reading this who supports the former will support the latter, and vice versa. This fact is troublesome, for the sensibility of restricting access to guns is in no way determined by the absence or existence of man-made climate change.

So why is it that those who want less taxes almost invariably want abortion taxes as well? Either the morality of abortion is in some way determined by the amount of money we forfeit to our government each year, or there is irrationality afoot. Knowing Americans, the latter is probably a safer assumption.

The sort of irrationality at work can be succinctly characterized as the human predisposition toward conformity. While our ancestors formed tribes to survive, we have formed tribes to express ourselves politically. The problem is that while tribalism may have been useful for surviving the struggles of nature, its usefulness does not translate into politics.

But why are American politics becoming so polarized in the first place? Surely, there must be sociopolitical reasons for the intense spike in political tribalism the United States has experienced in the last decade. Glenn Loury, Professor of Social Sciences and Economics at Brown University, says the main reason is identity politics — a political appeal made to people based on a component of their identity, such as race, religion or gender.

“There are times when the call of the tribe just might be a siren’s call when an excessive focus on ‘identity’ could lead one badly astray,” said Loury to a crowd of thousands of Brown students at the University’s 245th Opening Convocation in 2008. “What is more, I firmly believe that now is just such a time.”

When setting out to evaluate the dangers of identity politics, it is important to distinguish the differences between identity-based political appeals and identity-based political decisions. Certainly, there are instances in which it makes sense that a particular demographic would vote one way or another — low-income voters might vote for better social programs, or Jewish voters might support candidates who prioritize Israel. These are cases in which the effects of an issue are felt disproportionately by the people of one identity or another, and in these cases it makes perfect sense for people to vote based on identity.

The problem arises when media outlets, political movements and politicians begin to circumvent the use of policy-based appeals through identity-based appeals, which are intrinsically divisive.

Take, for example, the four largest American political movements of the current decade: Third Wave Feminism, Black Lives Matter (BLM), the Tea Party Movement and the Alt-Right Movement. While these movements span the entirety of the political spectrum, there is one thing they all have in common; they appeal to an identity and present a platform that is, in each case, predicated upon the idea that those who disagree with their goals are morally deplorable.

That is not to say that any of these movements are not addressing legitimate concerns, rather that their methods of mobilization are divisive and in some cases dogmatic. Whether it is a feminist yelling obscenities at her political adversaries, or a Tea Party member preaching about President Obama’s involvement in 9/11, these movements have been known to foster obsessed ideologues.

The causes of such bigotry are twofold. First, political movements centered around identity are inherently conducive to tribalism. When people of a shared identity unite and start focusing on what makes them different from others, it quickly creates and fosters an “us against them” mentality.

The second reason, which has contributed to identity-based political movements dating as far back as the Inquisition, explains the existence of people inside the identity-based political movements who do not match the target demographic. Many male feminists, black Tea Parties and white BLM supporters have been drawn to their respective movements by the allure of the heretic hunt.

The moment an individual accepts the sanctimonious premise of one of these movements, supporting its political goals becomes an essential moral imperative. To do otherwise is to live in apathy toward this issue, which you have just identified as morally crucial. It is no wonder then, that those who involve themselves in these movements often exhibit contempt towards those outside their movement.

And once you are convinced, expressing your contempt feels good. Few things are more satisfying for a feminist than calling out a perceived misogynist, or for an Alt-Right advocate to identify “political correctness.” This creates incentive for people to fabricate and exaggerate the racism, sexism or wrongness of others.

Think of how you feel at Spirit Week rallies. You stand in the bleachers, alongside hundreds of people with whom you share a facet of identity, and yell at those who are different from you. During Spirit Week, the entire school agrees to put on a facade of differentness along grade lines for the sake of the intra-grade togetherness it can produce. And it is exhilarating, yet mostly harmless, and at the end of the week we drop the facade and remember that none of us are superior to others because of the year we happened to be born.

Imagine that we had Spirit Week based on race rather than age. Imagine that it lasted not a week, but a lifetime. Imagine that every student was completely convinced that those in the other race groups were dead set on destroying them. What you have is a model for the sort of society identity politics is conducive to. While the aspects of exhilaration are retained, this sort of event is no longer harmless. People will be hurt not only by others contempt towards them, but also by their own contempt towards others.

The bottom line is that we must remember some truths. First, objective truth has nothing to do with your personal identity. Climate change is either man-made or it is not, and the answer to this question gives no regard to the color of your skin or the contents of your underwear. Second, just because someone looks like you does not mean you should think like them. This fact follows the first, but its iteration is warranted by its importance. Finally, we are best off making decisions as individuals, critically thinking about each issue we wish to develop a stance on rather than selecting opinions from the available platforms that match facets of our identities. If we remember these things, the marketplace of ideas will benefit, and our society will be thrust forward in a way that reaffirms the greatest aspects of democracy.