For as long as sports have been around, athletes have sought every competitive advantage available, both legitimate and fraudulent. Today, professional athletes are given a list of prohibited substances, which is overseen by the World Anti-Doping Association (WADA).

While it is widely known that performance-enhancing drugs are prohibited due to the unfair advantages they create in competition, there have been numerous loopholes around this restriction. An athlete’s ticket to using a banned substance without a penalty: the Therapeutic Use Exemption.

The 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympics thrust the topic of Therapeutic Use Exemptions into the global spotlight. A TUE is an agreement between an athlete and the WADA that allows the athlete to use a prohibited substance solely for the purpose of treating a legitimate medical condition. TUEs can be granted for anything ranging from Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) to asthma. The debate around TUEs has largely been about whether or not they are being abused by athletes.

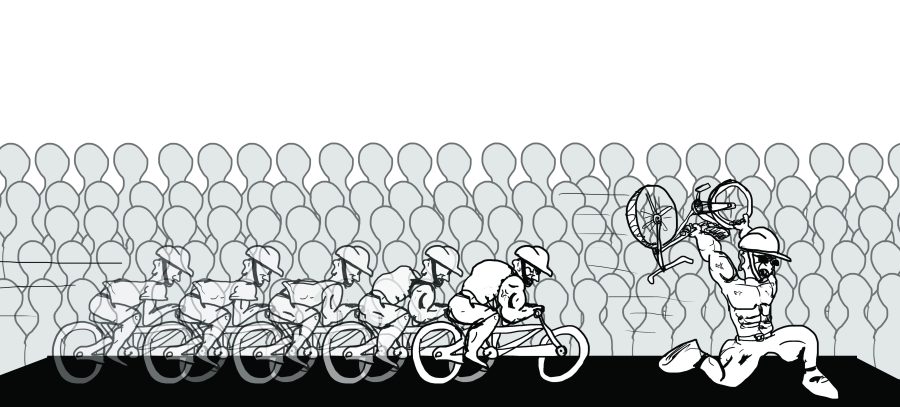

Knowing that top athletes use drugs that help them perform better has always left many with a visceral feeling. It continues to be ubiquitous in athletics despite the existing regulations. According to several scientific publications, what often compels an athlete to consume performance-enhancing drugs is the infinitesimally low chances of getting caught. If the athlete evades getting caught, they often reap incredible benefits, such as large sums of money through breaking records, gaining sponsors and getting better contracts.

According to Michael Shermer’s article “The Doping Dilemma,” approximately 50 to 80 percent of baseball and track athletes consume performance-enhancing drugs. Now, with a legal method to attain performance enhancing-drugs, an athlete is given even more incentive to cheat and abuse a broken system. The widely-discussed issue has highlighted that, provided high enough stakes, any immoral athlete may abuse the flawed TUE system.

An athlete’s use of TUEs is considered confidential, being part of their private medical records. However, following the 2016 Rio Olympics, a group of Russian hackers, dubbed “Fancy Bears,” began leaking an abundance of medical records.

The records, which were leaked in retaliation for the International Olympics Committee banning the Russian track and field team for alleged cheating, detailed the many Olympians who had obtained TUEs accompanied by the substances that they had been consuming and the specific dosages.

The list included renowned athletes, such as Spanish tennis player Rafael Nadal and American soccer player Alex Morgan. Fancy Bears wrote on its website that a TUE is an athlete’s license to dope.

Nonetheless, the plethora of leaked records show no illegal infractions.

“The use of TUEs is not a doping offense,” said Nicole Sapstead, UK Anti-Doping Chief Executive, in an interview with BBC news. “And all these athletes have legitimately applied for, and have been granted, medical support within the anti-doping rules.”

While there is no hard evidence indicating wrongdoings, the system is open to abuse by the unprincipled competitor. This begs a much larger question: how often are TUEs being abused, if at all?

“Some of the medical conditions used to justify a TUE can be difficult to validate; and as I discovered, an unscrupulous rider and doctor could exaggerate or simply make up symptoms that would merit a prescription and exemption.”

David Millar

Former Professional Cyclist

The majority of TUEs listed among the leaked records were stimulants generally prescribed to people with ADHD. However, stimulants also increase awareness and endurance. Another commonly prescribed drug was glucocorticosteroids, which allows athletes to perform with greater endurance.

While the distribution of TUEs supposedly has strict criteria, several have noted flaws in the system based on past experience.

On Oct. 14, David Millar, once famous as a professional road racing cyclist, wrote an opinion piece in The New York Times called “How to get away with doping.” The article detailed his career as a professional who used PEDs frequently throughout his career. Millar revealed that, not only is there a facile method to attaining a TUE, but also that obtaining them is encouraged within the professional cycling culture.

“Some of the medical conditions used to justify a TUE can be difficult to validate; and as I discovered, an unscrupulous rider and doctor could exaggerate or simply make up symptoms that would merit a prescription and exemption,” Millar wrote.

Millar’s article also warned about the dangers of consuming performance-enhancing drugs.

“In one sense, it would be like hitting a self-destruct button: the moment the drug entered my body, I would become catabolic,” he wrote. “The cortisone would start to strip me down, and I began to use my own body as fuel.”

Despite countless restless nights induced by the effects of the drugs, Millar admitted to having a surplus of energy during his drug-fueled athletic career. Through the use of TUEs, Miller said he would be able to push onto bigger gears for a longer period of time.

“On one occasion, I received a TUE for a fake tendon issue,” Millar wrote. “A doctor simply wrote a prescription for an ankle injury that required an intra-articular injection.”

Another factor playing a role in the TUE issue is the substantial number of banned substances on WADA’s list. The list includes over 300 banned substances, many of which have little research about their effects.

With the list growing rapidly, it is difficult to study the performance enhancing drug qualities of each substance, which leaves the WADA shadowboxing with many of the drugs.

“We’ve seen so many cracks in the anti-doping system that there’s bound to be some cracks in the TUE system,” said Richard Ings, former CEO of the Australian Anti-Doping Authority, in an interview with USA Today. “But this shouldn’t be about throwing out the entire system. There needs to be a process of allowing athletes to get medical treatment.”

With any flawed system, there must be a call for reform and, as always, the difficult part is prescribing a worthwhile solution to the diagnosed issue. The task ahead should be a reformed system which minimizes the possibility for abuse, yet still allows players to treat their conditions.

“The use of TUEs is not a doping offense. And all these athletes have legitimately applied for, and have been granted, medical support within the anti-doping rules.”

Nicole Sapstead

Anti-Doping Executive

What Millar and many other people have suggested as a solution is making WADA implement and enforce a restriction on taking any drugs during competitions. Allowing athletes to have the slightest trace of a performance enhancing drug during a competition gives them a substantial advantage, which in turn should result in a ban, regardless of the TUE. Additionally, people such as Millar are also advocating that TUEs should be reserved only for recovery or during training periods.

“For an athlete’s own well-being, it is better to face the fact of sickness or injury and withdraw from competition,” Millar stated in his article. “And for the sport’s well-being, it is better to avoid a system open to abuse and exploitation.”

The Fancy Bears leak revealed a flawed system that is open to abuse by thousands of athletes across the globe. It shows that, if the stakes are high enough, athletes would be willing to take advantage of a broken system even if it is unethical, so long as it is legal.***