[divider]Rock and roll concerts fill students’ weekends[/divider]

“Apowerful phrase in itself,” wrote an unidentified staff writer in a 1980 edition of The Campanile in reference to the sheer movement that was rock and roll. “The ultimate symbol of any existing generation gap. An event frowned upon by society’s elders, yet cherished by its youth. An entertainment medium that draws the most dedicated crowds in the bright light world.”

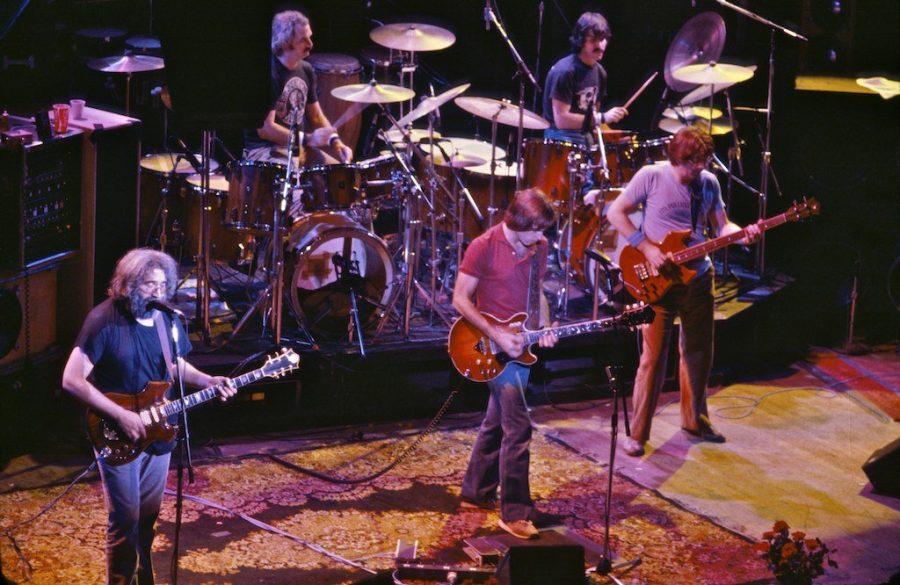

It’s no secret that rock dominated the ‘70s and ‘80s music scene, luring students to local venues to catch worshipped artists on tour. Students marveled at the opportunity to see The Who live in Oakland, Calif., and felt particularly passionate about following the Grateful Dead, the Palo Alto based band, to San Francisco for their New Year’s festival show.

“Everyone is there for one reason — to see one of the longest lived cult groups still in existence,” wrote staff writer Dan Spector in 1984 in reference to the Grateful Dead concerts. “There has to be something unique about a band which consistently sells out huge concert halls and open-air festivals and has a set of fans as dedicated as the ‘Dead heads.’”

While some concerts at the time were more erratic and could pose a dangerous atmosphere, the Grateful Dead offered a scene where listeners were peacefully swept up in the music.

“They set an easy, melodic base in an already relaxed atmosphere,” Spector wrote. “None of the pushing and shoving evident at other concerts is seen, just dancing.”

A more unusual destination at the time was the Laser Rock Show, which played on Friday and Saturday nights at the De Anza College planetarium.

“The laser rock performances offer loud music, psychedelic lighting and a bizarre change of pace,” wrote staff writer David Swope in 1984.

The shows toyed with the genre of Psychedelic Rock, combining Pink Floyd’s classic melodies into a soothing, exotic musical dream. Stereotypes about this time period lead present day students to imagine the ‘70s and ‘80s as time dominated by hippies, individuals who reject conventional values and gravitate towards illegal, hallucinogenic drugs. The reasoning for this belief is represented well in a 1984 article titled “Hypno-tapes help find one’s inner being.”

Swope writes that the “widely advertised, ever-popular hypno albums allegedly reach inside the subconscious — that real power center of one’s being!” He mentions that it was common for students to acquire the tapes, produced by famous hypnotist Barrie Konicov, and “listen to a genuine hypnotist tell a person how to breathe, while imagining himself being twisted, enlarged, purified, taken apart and reassembled to unlock his spiritual door.”

[divider]Weed obscurity and drug trafficking[/divider]

Marijuana was a mystery in the ‘70s and ‘80s. While the general consensus was that it was bad, the public had little to no idea of the ramifications of smoking weed and the toll it takes on the body.

Staff writer Pete Freund published an article in 1976 titled “Marijuana is bad, bad, bad,” hoping to reveal the harsh reality of the drug to his cannabis-crazed peers. He disclosed that the “active ingredient in marijuana — tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) — interferes with the function of cells and is uniquely accumulated in the body,” and that “the use of grass beyond three years may cause irreversible brain changes.”

At the time, according to Freund, “doctors [did not] know enough about marijuana to allow the public sale of it.”

There was little Freund or even distinguished scientists could do to stop the marijuana madness with minimal influence over the public, and the cannabis situation at Paly had amplified to involve the administration — but not in terms of prevention.

Following two months of thorough investigation, four staff members were arrested on Jan. 18, 1984 for drug trafficking — global illicit trade involving substances which are subject to drug prohibition laws — within school campus.

The discovery unnerved the parents, especially when it was revealed that in addition to marijuana and sinsemilla, marijuana with higher THC content, the convicted staff were also responsible for the distribution of cocaine and hallucinogenic mushrooms to high school students.

A student who bought illegal substances relayed that one convicted staff member had not been careful in executing the deal.

The Palo Alto Police Investigative Division and the Allied Agency Narcotics Enforcement Team concluded that “any person 18 years or older who prepares for sale, sells or gives away a controlled substance to any minor upon the grounds or within any school is subject to a felony charge, warranting a five to seven year sentence in state prison,” according to a 1984 account written by Peter Jacobson and Paul Stein.

[divider]Student government voted to be removed[/divider]

Imagine our school without the Associated Student Body (ASB); there would be no voice on behalf of the students to push for a better school climate. In February 1970, the majority of Paly students voted to abolish the student government.

According to a 1970 issue of The Campanile, written by Marchal Sanders, out of 1,458 students, 399 voted to keep student government, 486 voted to terminate it and 573 did not participate in voting.

In the 1970 article, former Student Body President Joe Simitian led the front against Paly’s student government, promising “no more hassle” in his campaign.

“Student government keeps many students from participating,” Simitian says. “The structure of the government as it was established at the time was not representative of student desires.”

There was a general consensus that one of the main purposes of student government was to filter through student complaints, according to the article. However, students believed it would be more efficient for administration to manage this criticism.

Although the overall attitude towards student government tends to be dismissive, the abolishment led to several mixed reactions.

“Any type of student government is better than none at all.”

Unidentified student

[divider]‘Wave’ Fashion, Music Popularized[/divider]

As the chapter of “Johnny Rotten, safety pins and torn T-shirts” faded, the New Wave of black suit jackets, flat leather oxfords and wraparound sunglasses consumed the latest fashion fad in 1980, according to an article in a 1980 issue of The Campanile by an unidentified staff writer.

According to the writer, there was an extreme difference between Punk and New Wave in terms of music, fashion and other forms of expression. While Punk involved aggressive music and offensive clothing, the writer said New Wave has a more “fun and futuristic” style.

“New Wave is becoming very high-tech,” the writer said. “Computers, as pins or as instruments, play a large part in New Wave fashion and rock.”

The use of electronics, lasers and rockets had an influence on the fashion of the ‘80s. For men, most outfits incorporated a black suit jacket from the ‘50s or ‘60s paired with a plain, white shirt and a narrow, striped tie. In a more casual situation, men would sport bowling shirts or plaid shirts with ankle hugging jeans.

Arguably the most important part of the look, accessories completed these outfits. Whether they were “buttons of a New Wave group, or actual cutouts of the group,” pins took one’s fashion to the next level, according to the 1980 article.

“The most important thing to realize about New Wave is that it’s limitless. The above descriptions are merely the average look. The possibilities are endless.”

Anonymous writer

This sense of unbounded creativity allowed for a more personal feel to one’s New Wave look.

Although hats did not make an appearance in New Wave fashion, longer hair with curls on top was fairly popular. While individuals would dye their hair a neon green or a bold pink during the Punk era, “the only hair dying that [went] on among New Wave fans [was] either jet black or white,” according to the article.

Haircuts during this new fad were typically longer, especially in the back, as Punk cuts favored short hairstyles from absolutely no hair to colorful mohawks.

According to the article, it is necessary to distinguish Punk and New Wave, as there are drastic differences that set the cultures of each apart.

The writer wrote, “New Wave is fun. It permits us to laugh at ourselves and at the world around us, behind us and ahead of us.”

[divider]Administration implemented a campus smoking area[/divider]

Around 40 years ago, teenagers could saunter into a convenience store to purchase packs of cigarettes well before the age of 18; smoking had not yet become a tabooed habit among high school students.

While administration had no hope of preventing the students from smoking on campus altogether, they sought out ways to decrease the buildup of smokers in the bathroom. The answer was found in the form of a designated smoking area located on campus.

In a 1976 editorial about the new addition to the school, student journalist Margaret Connor wrote that it had proven to be a good answer for many, including non-smokers, who could adapt their routes to avoid the area.

The advantage for administration was that it “[met] the teachers’ needs by not making them have to patrol a restroom and turn ‘policeman’ for the day,” according to Connor.

The adolescent need to rebel is inevitable, and students soon began to abuse their privileges by smoking and distributing marijuana in the smoking area, initiating parent backlash towards the school’s decision.

In February of 1980, student journalist and editor-in-chief of The Campanile Paul Chamberlain published an article detailing the escalating situation, writing that “over 200 Paly parents questioned the District’s policy regarding a designated smoking-area last Thursday as they filled the school auditorium for the second in a series of drug abuse programs.”

In the event to follow, parents attacked the policy vigorously and demanded its repeal, while Principal James Van banded with the counselors in defense of the instated smoking area.

“‘[The elimination of the smoking-area] would only serve to drive smoking back into the bathrooms and the bushes. Only a small part of usage takes place at school; if any impact is to be made on students, a cooperative effort on the part, of school and parents is needed.’”

Principal James Van

The principal fought back, conducting a strong argument; he claimed that if parents accepted the elimination of such areas as panacea, students would simply be prompted to move their smoking habits out of direct view.

“As a result, people will pretend chat a drug problem does not exist,” Van said. “Consequently, there will be no improvement in the situation.”

Following Van’s speech, some parents were swayed and shifted to his side; however, others remained unconvinced. After a lengthy battle, administration and parents came to a consensus that a mandatory drug information program must be implemented for students, enabling them to make better decisions regarding the use of drugs.

Chamberlain wrote, “although still being formulated, the program would include films and small group discussions, and Paly counselors have already begun meeting with parents to plan family workshops.”