Due to the sensitive nature of the topic, The Campanile changed the names of student sources.

[divider]Misconceptions[/divider]

When the final bell rings, signalling the end of a long school day, many students flock to the bike cages and parking lots to get off campus as quickly as possible. However, Paly student Anna chooses to stay at school long after the bell rings to avoid seeing her classmates near the center where she stays and risk having her living situation revealed. Campus also provides an escape from the chaos awaiting her at her apartment.

“That’s so Palo Alto” is a phrase often casually thrown around to refer to the assumption that everyone in this community is wealthy. The four words typically are not used with malicious intent; many students who let the phrase escape their lips are unaware of the insensitive undertones of it.

They do not realize their perception of who Palo Altans are excludes many individuals in the community who don’t fit the common stereotype of wealth and privilege. In reality, Paly students’ financial situations and living conditions span the spectrum and include those who fall under the legal definition of homeless.

“Homeless” is a term often associated with life on the streets: people finding shelter under overhangs and park benches, or with cardboard signs asking for spare change. However, the term “homeless” encompasses a larger range of living conditions beyond just the streets.

The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act of 1987 defines homeless children as “individuals who lack a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence.” According to the act, this includes students who “share housing due to economic hardship or loss of housing,” live in “motels, hotels, trailer parks, or campgrounds due to lack of alternative accommodations,” live in “emergency or transitional shelters,” have a primary nighttime residence that is not a place intended to be slept in (for example, benches in a park), or live in “cars, parks, public spaces, abandoned buildings, substandard housing, bus or train stations.”

Insensitive comments implying everyone in Palo Alto is wealthy can perpetuate a culture of ignorance and gravely affect the students who do not fall under those categories of privilege. These remarks stem from a lack of knowledge about underrepresented individuals.

According to PAUSD homeless education liaisons, it is crucial that our community members open their ears to the stories of those who have been marginalized.

[divider]Student Experience[/divider]

When Anna was in elementary school, her father lost his job and her family was forced to move out of their house in a town neighboring Palo Alto.

They moved into an apartment at the Life Moves Opportunity Services Center, located just north of Town & Country Village, where she has lived for the past nine years. The center provides hospitality and rehabilitative support for people who are homeless or at-risk.

“My apartment is split into two — one side for the family side, so basically, if a parent has kids, you’re on the family side, and there’s one for the homeless side, if you don’t have kids, then you’re in this small studio apartment and that’s it,” Anna said.

According to Anna, living at the Opportunity Center has presented her with many challenges, including being surrounded by residents who battle addictions. These residents often stir up drama at the Opportunity Center.

“There are people who are on drugs where I live, and obviously they can’t handle themselves and stuff like that, and they just want to take their stuff out on others,” Anna said.

The residents’ various mental states sometimes cause them to behave inappropriately, according to Anna. She has been verbally harassed multiple times while trying to walk up the stairs.

Disturbances in the Opportunity Center also result in residents and workers calling the police almost every day. Anna has been late to school as a result of police questioning her.

“Sometimes there will be police outside the OC and they stop people and question them and stuff like that because where the police go most is my apartment,” Anna said.

Though there hasn’t been an incident like this yet this year, according to Anna, she was stopped at least five times last year, which once caused her to have to go to school nearly two hours late. According to Anna, it can be extremely frustrating to have a simple routine of going to school be interrupted by a police interrogation over a situation that has nothing to do with her.

In conditions like these, having an understanding teacher makes a world of a difference.

“I try every year to find that one teacher that I really, really like and tell them [about my living situation] so I at least have one person on my side from the school who knows what I’m going through.”

Anna

Anna said she can go to these teachers with personal problems. Her trusted teachers have also helped her communicate with other teachers about her situation and figure out the best way to navigate obstacles that stand in the way of her getting assignments in on time.

“They give me my space and work around my problems and stuff like that and do the best they can to help,” Anna said.

Without having a teacher who knows about her situation, Anna said communicating about situations like coming to class late would be much more difficult for them to understand.

In addition to disrupting her education, Anna’s childhood innocence was cut short after moving to the Opportunity Center, where she was introduced to the issues of addiction and substance abuse.

“I was never exposed to that when I was younger. I was living with my brothers and both of my parents in a good community and stuff, and when moved to the OC, and I see all these people out there smoking and doing [drugs] and stuff like that, it was like, ‘Whoa, what did I just step into?’ It’s very hard growing up in that community.”

Anna

However, being exposed to this community and surrounded by people struggling with addictions has encouraged Anna to stay away from the substances as opposed to luring her into trying them.

“[I think about people from the OC and] I think about the people in my family too, because I have people in my family who are also on drugs,” Anna said. “I see them and I see my friends too, and I’m just like ‘I can’t end up like that,’ so I try to stay away from [drugs].”

When Anna’s father lost his job and her family transitioned into homelessness, Anna’s mother faced several struggles. In this time, she turned to drugs.

Her involvement with drugs caused her to begin to lose touch with her family. According to Anna, she wasn’t “capable of being a mother” during this time.

About two years after the move, Anna’s parents split up; Anna and her father stayed at the Opportunity Center and Anna’s brothers and mother began to travel from shelter to shelter, sometimes living on the streets. The two boys were in high school and attended Paly during this transition time.

Now, Anna’s brothers are in their mid-20s and are out of homelessness.

Witnessing the hardships caused by drug addictions and homelessness first-hand has made Anna more determined to do well in school and be successful in the future.

“It brings me motivation every single day, because my goal is to leave the OC and go somewhere else,” Anna said. “Being stuck there for my whole entire life just seems like a nightmare, so I just can’t do that.”

[divider]Disconnect[/divider]

Though the variety of financial statuses in the Palo Alto community is apparent to some, the RVs, food shelters and other hints at disparities in wealth are not enough to dispel the common misconception that everyone in Palo Alto is well-off.

Students are not the only ones who can be oblivious to this reality; teachers have also contributed to the stereotype.

When Anna was in seventh grade, she said she was assigned a partner project that required her to go to a destination that was farther than walking distance. At the time, Anna’s father did not own a car and she didn’t have the means of transportation needed to get to the location.

After approaching her teacher about the issue, she was accused of lying — the teacher refused to believe a student living in Palo Alto did not own a car.

“He was basically like, ‘Stop lying to me. I know your dad has a car, money for gas and all that stuff … and I know you can find a person who can take you. You have to help your partner for this project.’”

Anna

Anna continued to try to explain her financial situation to the teacher, but after a certain point, he just stopped listening, Anna said.

At the time, Anna didn’t think much of the incident. Though she was unsettled by the accusation, she was used to people making comments assuming everyone in Palo Alto is wealthy. She didn’t believe the situation with the teacher was significant enough to report to administration, she said. However, looking back on it, Anna has a different view of the incident.

“People just put people in one category and that is just not true,” Anna said. “There are so many people who aren’t in the same category as others, and I started to realize that now, as soon as I got to high school. That’s what changed my perspective on situations like that.”

Anna said if she were given the opportunity to talk to that teacher now, she would not let the incident slide.

“I would say, ‘Yeah, this is Palo Alto, but not everybody in Palo Alto has a car or has a house and this and that, so be more mindful of that instead of just assume that everyone is rich and has this and stuff,’” Anna said. “‘Keep your mind open.’”

Anna’s middle school years were littered with inconsiderate comments assuming everyone in Palo Alto is wealthy, usually made by her peers. According to Anna, in middle school, she became desensitized to comments and would just play along with them to be “cool.” When she entered high school, she began to see there are others in similar situations as her own.

However, despite realizing she is not alone in these matters, the disconnect between people’s perceptions of Palo Alto and the reality of some families’ financial situations has remained a prevalent issue. To this day, Anna has never felt comfortable enough to tell her friends that the apartment she lives in is part of the Opportunity Center.

When the subject of where she lives comes around, she always makes excuses for not being able to hang out at her home. If asked where she can be picked up, Anna asks to meet the person at a friend’s house or at Paly, since she lives so close to school.

“I’ll always make up stories and tell my friends that they can’t come over to my house and stuff like that, because I was just so embarrassed to bring them over. I don’t want them to see people doing drugs outside and it’s just a bad look.”

Anna

Anna said she hides her financial situation because she thinks her friends who live in houses in Palo Alto and have never experienced homelessness or financial struggles would not understand her situation.

“I wish I could talk to them about it to let them know why I don’t want to bring them over and stuff like that,” Anna said. “I feel like if I just talk to them about it they will just make fun of me that I live in an apartment [at the Opportunity Center].”

Though Anna does hope to one day be able to talk to them about the Opportunity Center, she doesn’t feel like it’s the right time.

“I’ll probably tell them when I’m fully comfortable that the OC is my home and that is where I come from,” Anna said.

Zendejas emphasizes that these numbers are deceptively small; they only include families that have identified themselves to the district and formally registered as homeless under McKinney-Vento. In reality, there are likely many more families have the same living conditions, but choose to keep that information in their private life.

[divider]Resources Around the Bay[/divider]

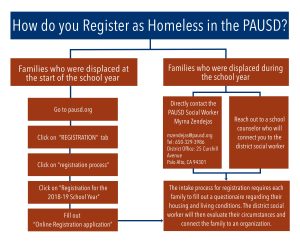

The first step to accessing resources in the District for students who qualify as homeless is determining whether or not that student’s family falls under the McKinney-Vento definition of homelessness. In order to get more information about their eligibility, families can go to the District office — located at 25 Churchill Ave., right behind Paly — to talk to a social worker about their situation and see what programs apply to them, according to PAUSD social worker and McKinney-Vento liaison Myrna Zendejas.

Once the student’s living situation is categorized, the district will take action to find what resources are best suited for that family’s needs. The McKinney-Vento Act plays a large role in this step.

“So the McKinney-Vento Act was established to support students who are living in transition so they don’t have a stable home,” Zendejas said. “It was developed to ensure that students in those conditions would have access to their education right away… Sometimes when families become homeless, they lose documents, and so it can make it harder for the kids to enroll in school. And what the Act does [is say], ‘Get the kids into the classroom and we’ll work on the paper as soon as we can, but don’t wait for the paperwork to come.’ It kind of gives the students the priority to be in school and gather information later.”

According to Zendejas, being able to attend school can provide a lot of support for a student with unstable housing situations.

“School is one of the stable things. They’ll come to school, they have routines, they’ll have lunch, they’ll have friends. We want to make sure that kids … feel safe [and] feel supported as their parents are working on other situations.”

Myrna Zendejas

In addition to ensuring students get into the classroom immediately, PAUSD works to connect with families who have registered as homeless with various resources. This assistance isn’t just offered to Palo Alto residents; PAUSD has students from cities all around the Bay Area and offers them with the same support. Though the District cannot directly provide any sort of financial relief, PAUSD is connected to many organizations around Palo Alto.

“We have partnerships in the community,” Zendejas said. “The Opportunity Center is one of our big partners — we always connect with them… We refer families there for services and they reach out to us when they have families coming in.”

For many, the Opportunity Center is a long-term residence. However, it also serves as a temporary home for families who are in transition, according to Zendejas. The Opportunity Center provides these families with the assistance they need to be able to get permanent housing.

According to Zendejas, the center offers a variety of family services to both center residents and non-residents. These services range from medical support and hygiene care to homework help and daycare.

“There’s a homework center I used to go to. [They] have volunteers from other schools like Paly [and] Stanford [who] help the kids with their homework.”

Anna

The after-school tutoring program also provides students with free school supplies.

In addition to assisting students in their academic journeys, the Opportunity Center helps families with more basic human needs, such as clothing. People can take clothes from the donation closet and use the communal washing machines to clean their laundry.

According to Anna, the most useful accommodation has been the food pantry.

“My family has the hardest time keeping food in the house and when we run out I can always go to the food pantry they offer us and grab whatever I need,” Anna said.

[divider]Then and Now[/divider]

It can be easy for those in unstable living conditions to let years of moving from place to place take a toll. However, many individuals don’t allow themselves to be worn down by hardships — instead, they become motivated to get out of their current situations and move on to achieve their goals.

One example of someone who bounced back from difficult years spent homeless is the father of Paly student Nicole. In his mid-20s, he went around London squatting, (a term to describe illegally sleeping in uninhabited buildings). During the time he was homeless, he worked a low-income job as a printer. Many years of hard work added up and eventually, he was able to become financial stable enough to start a family in a home of his own.

“When I look at him, he’s not really someone who I would think of as someone who was homeless at some point. So it sort of makes you realize that even people who don’t look homeless could have been or be. There’s sort of a stereotype of homeless people.”

Nicole

Anna’s brother also has an inspiring story of coming out of homelessness. After living in the streets and going from shelter to shelter in high school along with his mother and older brother, he attended community college for two years. He then went into the workforce and was able to build himself up until he became entirely self-supporting. Today, he also supports his mother, who lives under his roof.

“I do look up to one of [my brothers],” Anna said. “Him just working really hard and finding a job and making money, and now that he has a house on his own, it’s just like, ‘Wow, maybe I can do that.’”

[divider]Call to Action[/divider]

Before being interviewed for this article, Anna knew little about homelessness in PAUSD; she was not aware of McKinney-Vento or that her living situation qualifies as “homeless.” After learning more about the resources around the Bay Area and the McKinney-Vento definition of student homelessness, Anna said she plans on looking into it more.

It is reasonable to assume that many students, like Anna, are unaware of what their housing conditions mean. Without properly publicizing this information, it is difficult for students to utilize the various resources available. Therefore, this information should become more accessible to families in PAUSD, according to Zendejas.

Students who think they may qualify as homeless or want to seek help from the district for any sort of living situation can start by talking to a school counselor or going directly to the district office to ask for more information about McKinney-Vento and resources in the area.

In Anna’s case, reaching out to teachers benefitted her academic experience tremendously. Raising awareness within the faculty would help encourage teachers create a more welcoming environment for students to come to teachers for support, according to James Hamilton, the guidance counselor for the Class of 2019.

“I feel like [teachers encouraging students to approach them with issues] would be effective because that would give so many kids in my situation [the chance] to open up and instead of going through all of this hard work themselves and not have help from their teachers or peers [to be there for them],” Anna said.

According to Hamilton, hosting faculty workshops in order to educate teachers about the various living conditions of underrepresented students can be beneficial to both staff and students.

When Hamilton worked as a counselor in the Sanders Unified School District #18, the administration made a strong effort to ensure all teachers were informed about the circumstances some of their students were dealing with. They presented a slideshow containing pictures of some of the housing the students resided in.

“It was a very sobering moment for our faculty. As a teacher, you can get frustrated with kids … To see these houses that the people were living in, that were made out of scrap wood or clay, I think it was really hard and a real wake up call for a lot of teachers who were like, ‘Damn, I didn’t realize.’”

James Hamilton

Though the living conditions of Paly students may be different than those of Sanders, it is equally important teachers understand the struggles their students face outside of the classroom, according to Hamilton.

Anna said her experience living among other homeless individuals, some of whom struggle with substance abuse, has made her more empathetic to people in these situations.

“They’re people just like us, just not with a home,” Anna said. “I [have become] more understanding because it’s not [their] fault that [they’re] homeless, so there’s no reason for me to treat [them] like a different person.”