When sophomore Dani Colman hears someone say that cheer is not a real sport, she flashes back to all the hard practices she has endured and the blood, sweat and tears that she’s poured into it.

“I think a lot of the time people don’t realize how much work goes into competitive cheerleading,” Colman said. “People make fun of it for being ‘easy’ and ‘not a sport’ when in reality it’s really physically demanding and takes a lot out of you. A lot of times, people tell me that anyone could be a cheerleader. It’s a lot harder than that, and people don’t realize what it takes.”

When most people think of cheerleading, they think of standing on the sidelines of a basketball or football game, waving pom-poms and demanding the crowd to shout a certain letter. The type of cheer they are envisioning is high school, college or professional cheer.

However, there is a whole other realm of cheer: all-star cheer. Also known as competitive cheer, this sport has evolved into a combination of acrobatics, gymnastics and dance.

The difference between all-star and high school cheer is that all-star cheerleaders don’t cheer at games. Rather, they train to perfect a two and a half minute routine that is performed for the whole season at competitions.

Despite its name, there is no cheering aspect in all-star cheerleading. Most routines have seven components.

The first component, which is often performed in the beginning of a routine, is standing tumbling, in which a skill is done from a standing position with no forward momentum. This includes standing back handsprings, where one jumps backwards onto their hands in a handstand, then pushes off the floor to an upright standing position.

These can be connected into backwards flips such as back tucks, back layouts or full twisting layouts, where one flips and spins at the same time. The difficulty of the flip depends on the athlete’s level, which ranges from one to six, with level six being the highest.

Another component is running tumbling, where a pass, or series of skills, is initiated by forward momentum. These passes usually start out with running roundoffs, which are cartwheels landed with two feet to gain enough power for a rebound. These can be connected with backwards flips, as well.

Colman, a cheerleader at NorCal Elite All-stars, a competitive cheer gym in the Bay Area, finds stunts to be the most rewarding part of a routine.

“My favorite part of the routine is stunting, because it’s usually the hardest part and it’s really the biggest aspect of cheerleading,” Colman said. “Especially when you hit all your stunts and both you and the crowd have so much energy and everyone is cheering for you.”

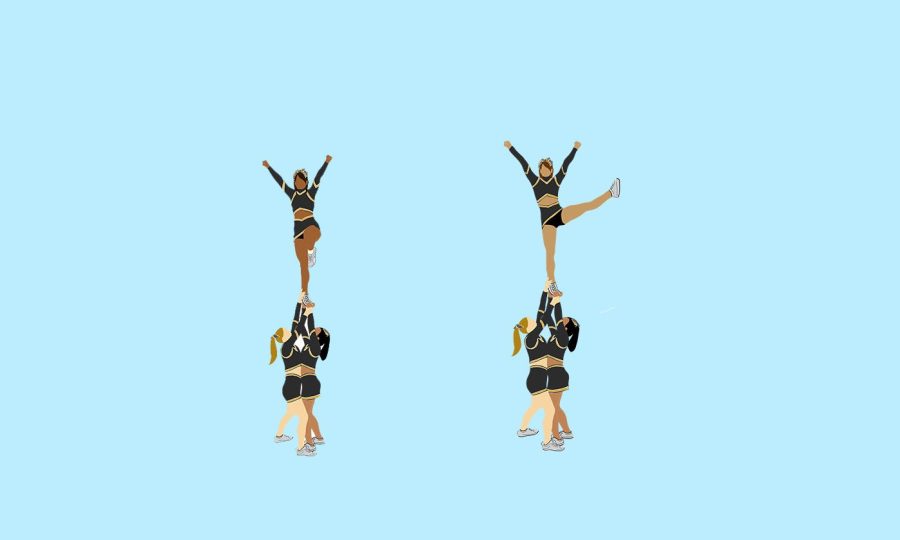

One of the most important components are elite stunts, which are stunt sequences in which two to three athletes hold up another person called a flyer, who spins or pulls different body positions. These are crucial to the success of the performance because stunt falls are one of the biggest deductions at competitions.

“You take all the energy you have left in your body and dance your heart out.”

Sophomore Ella Spanhook

Routines also often incorporate jumps, which can be a series of toe touches, hurdlers or pike jumps. These jumps require strong legs, as the athlete must get enough height to split their legs midair.

Another aspect is baskets, where a flyer is thrown into the air and caught. In higher levels, the flyer twists or flips in the air before being coming back down.

The most recognizable aspect is the pyramid section, where flyers connect and assist one another in flips or other stunts. In level six, athletes can perform three-level pyramids, where the bases hold a flyer who holds another flyer.

The seventh and final component is a dance which typically occurs at the end of the routine.

“You are in a room with 200 people who have the exact same goal as you, but only some of you will make it.”

Sophomore Dani Colman

Paly sophomore and cheerleader Ella Spanhook, who also cheers at NorCal Elite All-Stars, enjoys the dance aspect of the routine.

“My favorite part of the routine is the dance, which is typically at the very end, when you’ve hit your whole routine and you take all the energy you have left in your body and dance your heart out,” Spanhook said.

Because all-star cheer is a year-round sport, cheerleaders are almost always training in some way, even outside of competition season.

Tryouts are held in May, which lead to team placements based off of the cheerleaders’ tumbling and stunting skills. Once teams are made, the athletes train throughout summer to work on the different elements, like standing tumbling, running tumbling and stunting.

Colman finds tryouts to be a nerve wracking experience each season.

“Tryouts are a really stressful experience,” Colman said. “Especially with more well-known and competitive gyms, you are in a room with 200 people who have the exact same goal as you, but only some of you will make it.”

Around August and October, the routine gets put together by using choreography from coaches or professional choreographers to transition between the seven components.

“Choreography is very exiting because you are getting to see your routine that you will compete for a whole season,” Spanhook said. “But at the same time it’s very exhausting because you are asked to do stunts you might not have ever performed before and you have to learn them very quickly. There is also a lot of standing around for up to ten hours.”

From November to April of the following year, the competition season starts, and teams attend local or national competitions. During the end of April or the beginning of May, select top teams attend Worlds or Summit, which are generally the two biggest and most intense competitions out of the entire season. More than 11,000 cheerleaders from all over the world compete at The Cheerleading Worlds each year.

The Summit is essentially the same as Worlds but is held for a wider range of levels. Levels one through five able are to attend. About 12,000 teams from all over the nation will compete at Summit in 2019. Many teams’ ultimate goals are to win Worlds or Summit at the end of the season.

Worlds and Summit are both held in the ESPN Sports Center at Disney in Orlando, Fla. and NCA (National Cheerleaders Association) is held in Dallas. “For most cheerleaders, it’s an honor to even get a chance to go to any of these competitions,” Spanhook said. She has never attended Summit but has plans on going this season.

At competitions, whether they are local or national, teams perform their routine in front of an audience and a panel of judges, who take into account the routine’s difficulty, execution, technique and more to produce a score between zero and 100. The team with the highest score in their division wins.

“Cheer competitions are very intense and nerve-wracking but also very fun and exciting at the same time,” Spanhook said. “There are local competitions against small gyms in the area and national competitions where you are against (more well-known) big gyms. In 2016, NCA Nationals had over 25,000 athletes competing.”

Divisions vary based on level, size and whether or not they are co-ed. Size varies from extra small to large, which refers to the number of athletes that team has.

The main difference between all-girls teams and co-ed teams is that co-ed teams are expected to have partner stunts, which are stunts in which a single athlete holds up the flyer. However, despite not having to meet this requirement, all-girls teams often have strong girls that are able to partner stunt.

Will Cooper, a senior at Los Gatos High School and cheerleader at NorCal Elite All-Stars, has been cheering for two years and is on a level three team where he is required to partner stunt.

“While cheerleaders do wear makeup and do their hair for competition, our main focus is hitting our routine.”

Sophomore Ella Spanhook

“As a male cheerleader I feel like I have to try to be as good or better than the girls because it is a female dominated sport,” Cooper said. “I try harder to stand out in a sea of sass.”

Cooper thinks people often underestimate the difficulty of cheer.

“I haven’t faced any discrimination per se but when starting the sport my dad didn’t recognize it as a real sport,” Cooper said. “Cheer is often overshadowed and looked at as just girls chanting, but in reality it is a contact sport. Cheerleaders have to be in top shape because of the amount of stuff fit into the routine. And not only do you have to be in shape and able to do everything asked of you, but you also have to perform and make everything look effortless.”

“As a male cheerleader I feel like I have to try to be as good or better than the girls because it is a female dominated sport.”

Will Cooper

With so many different elements to a single routine, cheerleaders generally have to have a wide skill set, as they need to strong, flexible and able to tumble. Colman said there are misconceptions about the difficulty of cheer.

“I think people don’t really understand how physically challenging it is because the cheerleading they’re used to seeing is all on the sidelines,” Colman said.

Cheerleaders also need a high stamina, as the two minutes and 30 seconds on the mat are packed with skill after skill with little to no time for a break.

“A fullout is when you do your entire routine from start to finish without stopping — every jump, every stunt, every tumbling pass,” Colman said. “It happens so quickly — you barely get a chance to breathe. When you’re in a fullout, you can’t stop. Even if you feel like you’re going to pass out, you have to keep pushing. It’s our job as cheerleaders to make it look easy.”

Along with a high stamina, these athletes need a strong mentality to get through the routine.

“In the routine, it often feels like you can’t keep going,” Colman said. “You just have to keep telling yourself that you can do it and helping each other out. Because it’s such a team sport, there is no stopping. During Nationals, a girl on my team broke her hand on stage in the middle of the routine, but she still stunted and tumbled. You can break a bone or pull a muscle on stage and you’re still expected to keep going.”

According to Spanhook, another misconception about cheer is that the sport is focused more on looking attractive rather than the actual physical aspect.

“Whenever people hear that we are cheerleaders, they tend to assume it’s all about waving pom poms and looking pretty, but in reality, it’s an extremely difficult and underestimated sport,” Spanhook said. “While cheerleaders do wear makeup and do their hair for competitions, our main focus is hitting our routine.”

While all-star cheer is often mistaken for high school cheer, the two have many differences. High school cheerleaders train to perfect a different routine each week that they perform at halftime of various games. In addition, school cheer is often focused more heavily on stunting or dancing and less so on the other aspects that all-star cheer is revolved around.

Many cheerleaders such as Colman say competitive cheer can be a huge commitment and require enormous amounts of dedication. Most teams practice two or more times a week throughout the year, and during competition season, competitions take up the whole weekend. “On competition weekends, I do my homework on the plane there, cheer and compete all weekend, study on the ride back, get home at 3 a.m. and wake up later for school,” Colman said.

Athletes are expected to attend every practice, since cheer is a team sport, and it is hard to perform the routine with athletes missing. “For most of us, cheerleading is our lives and we practice up to 35 hours per week,” Colman said.

“During nationals, a girl on my team broke her hand on stage in the middle of the routine, but she still stunted and tumbled.”

Sophomore Ella Spanhook

This causes each athlete on the team to work together and trust one another.

Spanhook said, “I love cheer because of the bond you create with your teammates. You can have a completely new team and become best friends with every single person in the span of just a few months. You have no choice but to become close with them because you have to work together in order to achieve greatness.”