East Palo Alto education

Examining the impacts of the lawsuit that intertwined the neighboring communities of Palo Alto and East Palo Alto

Each school day, junior Carl Wolfgramm wakes up at 5:45 a.m., takes the 6:47 a.m. 280 Samtrans and arrives at school at 7:15 a.m. He could take the 7:47 a.m. shuttle but chooses commitment to education over leisure.

For a “Tinsley student,” success in the Palo Alto Unified School District (PAUSD) takes detailed planning and continual effort in areas that Palo Alto residents have never experienced and will never have to experience.

“It is pretty frustrating and exhausting waking up very early in the morning just to get over the ramp to school compared to kids who live in Palo Alto and don’t have to worry about being late,” Wolfgramm said. “But at the end of the day, it’s worth the pain because I need to go to school and get an education that will pay off in the future. Education is part of my grind.”

For the past 30 years, the Volunteer Transfer Program (VTP), also referred to as the “Tinsley Program,” has mandated the acceptance of 166 students of color per grade living in East Palo Alto to surrounding school districts, including 60 to PAUSD.

After Highway 101 was expanded to create an even more pronounced physical barrier between East Palo Alto and Palo Alto in the 1950s, the racial gap increased drastically with differences in housing prices matching the trend. Ravenswood High School was opened in 1959, drawing almost all African-American students in the area and leaving most other high schools with almost 100 percent White enrollment. After more than a decade of attempting to desegregate high schools in Menlo Park, Redwood City, Palo Alto, East Palo Alto and other nearby districts, the affluent White community of neighboring cities around East Palo Alto used its political clout to force the closure of Ravenswood High School as the solution to the area’s lack of funding in 1976. Immediately afterwards, the movement for desegregation of education in the area took traction and for the next 10 years, a fight for the Tinsley Program ensued.

In 1987, the VTP emerged out of the settlement of the lawsuit questioning the legality of the discrepancy of education between the self-segregated cities. One hundred seventy plaintiffs, comprised of parents and students in Ravenswood City School District, argued that their community of almost entirely minority residents received a lesser education. Due to the settlement, almost 2000 students are bussed to seven different districts every day in hopes of acquiring a superior education.

Because of minimal “data-driven” decisions and reports from PAUSD regarding exclusively the VTP, The Campanile takes a deeper look into the program’s effects.

The Tinsley Program was created with the goal to “reduce the racial isolation of students of color in the Palo Alto, Ravenswood and other San Mateo County School Districts, improve educational achievement of Ravenswood students and enhance inter-district cooperation,” according to PAUSD’s website.

Studies have been conducted evaluating the program’s impact on educational achievement using a comparison in standardized test scores. At the elementary and middle school levels, VTP students exhibit slightly higher levels of academic achievement than students who stay in Ravenswood upon examination of Academic Performance Index (API) scores and research conducted by Kendra Bischoff for a dissertation for a PhD in sociology from Stanford University. The average API score, a measurement of achievement on standardized tests between 200 and 1000, for Ravenswood schools was 722 for the 2012-2013 school year. In comparison, PAUSD received a score of 768 for socioeconomically disadvantaged students (a score for solely VTP students is unavailable, as such “socioeconomically disadvantaged” is used as the closest representation). Bischoff presented in 2012 that VTP students “show ‘very small positive effects’ in math and English compared with students who applied — but were not admitted — to the program,” according to Chris Kenrick of the Palo Alto Weekly and “‘large positive effects’ and ‘significant differences’” in history and science. According to Bischoff, the statistics suggest clear benefits of the Tinsley Program in K-8 schooling.

But in order to give Tinsley students the help PAUSD believes they need, PAUSD uses special-education programs.

“Bischoff found that students in the program are ‘about 10 percent more likely’ to be in special education than students who had applied, but were not accepted, to the program and stayed in Ravenswood,” Kenrick stated. “‘[This tendency] can put kids on different trajectories in terms of classes they’re taking.’”

Bayinaah Jones, a previous East Palo Alto resident, discovered much less of an improvement in her dissertation examining the background and impact of the Tinsley Case decision.

“There is overwhelming evidence that no marked improvement in the collective educational achievement of African American students [in relation to] white students came as a result of the Tinsley case,” Jones stated in her dissertation.

Despite test scores displaying academic benefits to those admitted to the program, Jones found no improvement in the overall achievement of all Ravenswood students.

Additionally, 16.3 percent of socioeconomically disadvantaged students and 24.1 percent of English learners dropped out in the 2012-2013 school year, according to the Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC) report released on Feb. 2. There have been no statistics released by the district regarding VTP students dropout rates. As such, these categories are the most accurate representations of VTP students, as only approximately 33 percent of African-American students are a part of the Tinsley Program and 66 percent of VTP students are described as socioeconomically disadvantaged.

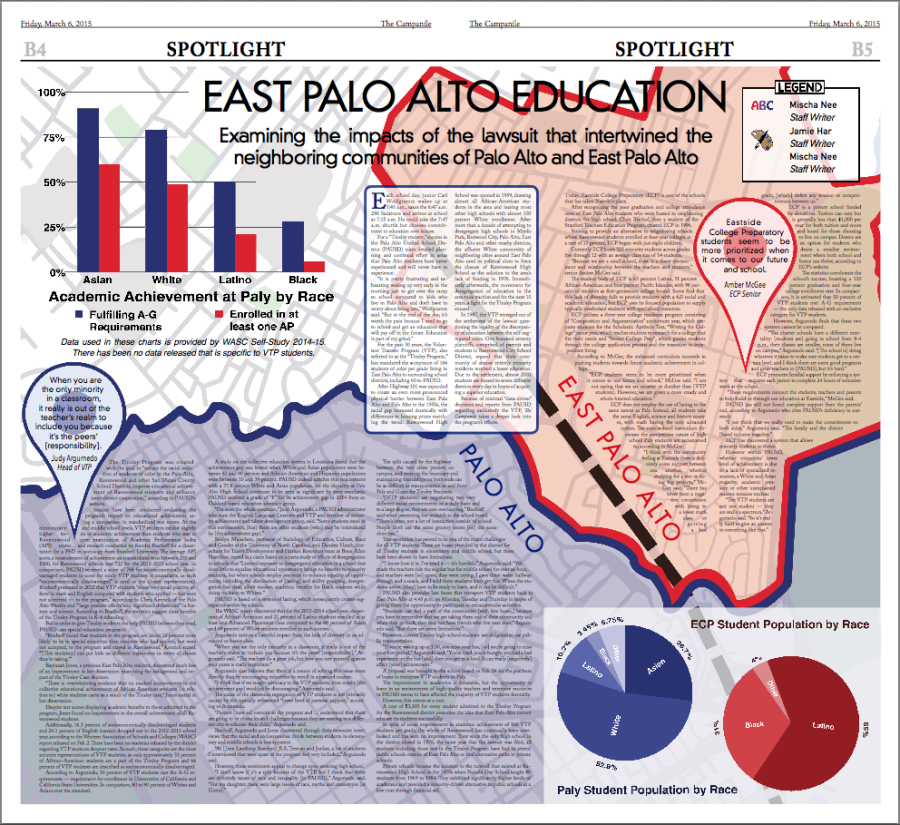

According to Argumedo, 50 percent of VTP students met the A-G requirements — requirement for enrollment in Universities of California and California State Universities. In comparison, 80 to 90 percent of Whites and Asians met the standard.

A study on the collective education system in Louisiana found that the achievement gap was lowest when White and Asian populations were between 61 and 90 percent and African-American and Hispanics populations were between 10 and 39 percent. PAUSD indeed satisfies this requirement with a 77.8 percent White and Asian population, yet the disparity at Palo Alto High School continues to be seen as significant by state standards. PAUSD received a grade of “F” for its achievement gap in 2014 from an Oakland-based education advocacy group.

“I’ve seen the whole spectrum,” Judy Argumedo, a PAUSD administrator who runs the English Language Learners and VTP and member of minority achievement and talent development group, said. “Some students excel in this environment, [but] there are other students [who] may be intimidated by [the achievement gap].”

Roslyn Mickelson, professor of Sociology of Education, Culture, Race and Gender at the University of North Carolina, and Damien Heath, consultant for Talent Development and Human Resources team at Booz Allen Hamilton, stated in a claim based on a meta study of effects of desegregation in schools that “Limited exposure to desegregated education in a school that does little to equalize educational opportunity brings no benefits to minority students, but when schools employ practices to enhance equality of opportunity, including the elimination of [laning] and ability grouping, desegregation has clear, albeit modest, academic benefits for Black students while doing no harm to Whites.”

PAUSD is based on a system of laning, which consequently creates segregation within its schools.

The WASC report discovered that for the 2013-2014 school year, six percent of African-American and 21 percent of Latino students enrolled in at least one Advanced Placement class compared to the 60 percent of Asian and 49 percent of White students enrolled in such courses.

Argumedo notices a harmful impact from the lack of diversity in an advanced or honor class.

“When you are the only minority in a classroom, it really is out of the teacher’s realm to include you because it’s the peers’ [responsibility],” Argumedo said. “The teachers do a great job, but how you rate yourself against your peers is really important.”

Argumedo also believes that there is a means of solving this issue more directly than by encouraging minorities to enroll in advanced courses.

“I think that if we taught advocacy to the VTP students, then maybe [the achievement gap] wouldn’t be discouraging,” Argumedo said.

The cause of the classroom segregation of VTP students is not primarily caused by the typically referenced “lower level of parental support,” according to Argumedo.

“Parents [have to] commit to the program and … understand that there are going to be obstacles and challenges because they are coming to a different city to educate their child,” Argumedo said.

Bischoff, Argumedo and Jones discovered through their extensive interviews that the racial and socioeconomic divide between students in elementary and middle schools is less apparent.

“At [Jane Lanthrop Stanford] JLS, Terman and Jordan, a lot of students I interviewed that were apart of the program feel very included,” Argumedo said.

However, these sentiments appear to change upon entering high school.

“I don’t know if it’s a split because of the VTP, but I think that there are definitely issues of race and inequality [in PAUSD],” Argumedo said. “For my daughter, there were large issues of race, myths and stereotypes [at Gunn].”

The split caused by the highway between the two cities persists on campus, and crossing the boundary and maintaining friendships on both ends can be as difficult as transportation to and from Paly and Gunn for Tinsley Students.

“[VTP students] are negotiating two very different social environments on a daily basis and to a large degree, they are non-overlapping,” Bischoff said when presenting her research to the school board. “There’s often not a lot of interaction outside of school. People don’t use the same grocery stores [or] the same churches.”

Transportation has proved to be one of the major challenges for all VTP students. There are buses provided by the district for all Tinsley students in elementary and middle school, but these have been shown to have limitations.

“I know how it is; I’ve tried it — it’s horrible,” Argumedo said. “We made the teachers ride the regular bus for middle school for over an hour, and teachers were [so] upset, they were crying. I gave them water halfway through and a snack, and I told them students don’t get this. When the students arrive, [they] have to be ready to learn, and it can be difficult.”

PAUSD also provides late buses that transport VTP students back to East Palo Alto at 4:45 p.m. on Monday, Tuesday and Thursday in hopes of giving them the opportunity to participate in extracurricular activities.

“Students can feel a part of the community [with late buses,] because you have to remember that we are taking them out of their community and when they go back, they may not have friends who live next door,” Argumedo said. “But there are some limitations.”

However, current Tinsley high-school students are obligated to use public transportation.

“If you’re waking up at 5:30, you miss your bus, [so] you’re going to miss your first period,” Argumedo said. “You’re tired, you’re hungry, you had a bad experience on the bus [and] then you get to school. It can really [negatively] affect [your] achievement.”

A proposal was brought to the school board on Feb. 24 for the purchase of buses to transport VTP students to Paly.

The improvement in academics is debatable, but the opportunity to learn in an environment of high-quality teachers and extensive resources in PAUSD seems to have affected the majority of VTP students favorably.

However, this comes at a cost.

A cost of $3,300 for every student admitted to the Tinsley Program for the Ravenswood district promotes the idea that East Palo Alto cannot educate its students successfully.

In spite of some improvement in academic achievement of 166 VTP students per grade, the whole of Ravenswood has continually been overlooked and has seen no improvement. Ever since the only high school in the district closed in 1976, the same year that the lawsuit was filed, all students including those not in the Tinsley Program have had to attend public schools outside of East Palo Alto or find alternative paths in private schools.

Private schools became the solution to the turmoil that existed at Ravenswood High School in the 1970s when Nairobi Day School taught 80 students from 1969 to 1984. They exhibited significantly higher levels of academics and provided a minority-driven alternative to public schools at a low-cost through financial aid.

Today, Eastside College Preparatory (ECP) is one of the schools that has taken Nairobi’s place.

After recognizing the poor graduation and college attendance rates of East Palo Alto students who were bussed to neighboring districts for high school, Chris Bischof, then a student of the Stanford Teachers Education Program, created ECP in 1996.

Striving to provide an alternative to neighboring schools where Ravenswood students enrolled at four-year colleges at a rate of 10 percent, ECP began with just eight children.

Currently ECP hosts 325 minority students across grades five through 12 with an average class size of 14 students.

“Because we are a small school, there is a closer environment and relationship between the teachers and students,” senior Amber McGee said.

The student body of ECP is 65 percent Latino, 31 percent African-American and four percent Pacific Islander, with 98 percent of students as first-generation college bound. Some find that this lack of diversity fails to provide students with a full social and academic education, but ECP uses its focused population to supply typically overlooked students with specialized resources.

ECP utilizes a three-year college readiness program consisting of “Composition and Argumentation” sophomore year, which prepares students for the Scholastic Aptitude Test, “Writing for College” junior year, which teaches students to research for a college that fits their needs and “Senior College Prep”, which guides students through the college application process and the transition to independent living.

According to McGee, the enhanced curriculum succeeds in pushing students towards future academic achievement in college.

“ECP students seem to be more prioritized when it comes to our future and school,” McGee said. “I am not saying that we are smarter or dumber than [VTP students]. However, we are given a more steady and whole-hearted education.”

ECP does not employ the use of laning to the same extent as Paly. Instead, all students take the same English, science and history courses, with math having the only advanced option. The standardized curriculum decreases the competitive nature of high school Paly students are accustomed to, according to McGee.

“I think with the community feeling at Eastside there is definitely some support between one another, whether studying for a test or doing big projects,” McGee said. “There has never been a negative connotation with being in a lower math class or getting a bad grade, [which] defers any tension or competitiveness between us.”

ECP is a private school funded by donations. Tuition can vary but is generally less than $1,000 per year for both tuition and room and board for those choosing to live on campus. Dorms are an option for students who desire a steadier environment where both school and home can thrive, according to ECP’s website.

The statistics corroborate the school’s success, boasting a 100 percent graduation and four-year college enrollment rate. In comparison, it is estimated that 50 percent of VTP students met A-G requirements — the only data released with an exclusive category for VTP students.

However, Argumedo finds that these two systems cannot be compared.

“The charter schools have a different mentality: [students are] going to school from 8-4 p.m., their classes are smaller, some of them live on campus,” Argumedo said. “[The school is] doing whatever it takes to make sure students get to a certain level, and I think there are some good programs and great teachers in [PAUSD], but it’s hard.”

ECP promotes familial support by enforcing a system that requires each parent to complete 24 hours of volunteer work at the school.

“These requirements connect the students, teachers and parents to help build us through our education at Eastside,” McGee said.

PAUSD has still not found complete support from the parents’ end, according to Argumedo who cites PAUSD’s deficiency in outreach.

“I just think that we really need to make the commitment on both sides,” Argumedo said. “The family and the district [have] to come together.”

ECP has discovered a system that allows minority students to thrive.

However within PAUSD, whether minorities’ lower level of achievement is due to a lack of specialized resources, a White and Asian majority, academic pressure or other unexplained reasons remains unclear.

“The VTP students are not one student — they are really a spectrum,” Argumedo said. “So it’s really hard to give an answer to something like that.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Palo Alto High School's newspaper