Why are Palo Alto schools so desirable? In short, our schools are home to devoted teachers; in addition, students may participate in a plethora of academic and extracurricular activities centered around their interests. Unlike other schools in nearby areas and across the nation, Palo Alto schools provide us with many opportunities to enlighten ourselves with challenging and intellectually engaging courses — most notably the great variety of Advanced Placement (AP) classes.

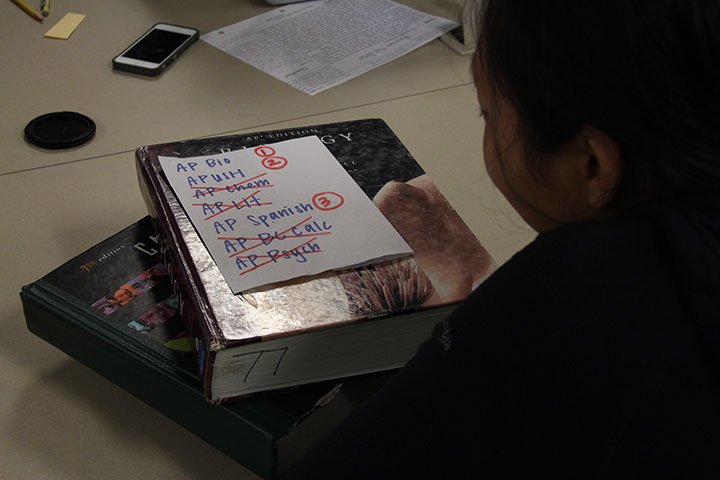

Palo Alto High School upperclassmen are fortunate to be allowed to enrich themselves with AP courses in both the humanities and the sciences. Students often see honors and AP courses as a means to challenge themselves and find their limits, and many pride themselves by enrolling in such courses. For years, students have found success in taking Paly’s 19 AP courses and 13 honors courses. With honors and AP courses, students can explore a college-level class, where teachers may delve deeper in concepts of their own interests.

Some may believe that the sole purpose of an AP class is to obtain the extra grade point on a transcript, and the AP program only creates hostility within classrooms across the nation. However, at Paly, where teachers are devoted to student success, students desire to expand their intellectual capacities and reach new realms of learning. Creating a mandatory cap and prohibiting students from taking more than three AP classes would hinder student potential and yield students less freedom for personal pursuits. This would concede two out of line notions: assuming that a strict cap on the number of AP classes students may take is fair, such a cap creates the precedent that all AP classes require the same amount of time and effort to succeed in and that all students learn to the same extent during any given class period.

Let’s imagine a realistic hypothetical situation where a junior excels in math and science and is restricted by an AP cap. Let’s also say given this student’s junior year performance, he or she has proven to be capable of taking honors and AP classes with success. Let’s say this student chooses to take AP Calculus AB and AP Chemistry to fulfill fourth-year math and science requirements. For social studies, because most senior year social studies classes span one semester, this junior figures that taking second semester AP Macroeconomics after first semester Economics is reasonable. This senior already has a schedule of three AP classes. But what if this student enjoyed American Literature Honors last year and wanted to continue in the high lane? What if he or she desires to pursue a secondary love for environmental science? What happens if he or she wishes to challenge his or herself while fulfilling the visual arts requirement by enrolling in AP Music Theory or AP Art History?

Tough luck.

We must realize that not every AP class is created equal; more importantly, just because an AP class is standardized to some extent by a test, students are not. There remains no question that AP classes offered at Paly range greatly in difficulty and workload. Each course covers completely unique content, yet an AP cap would fail to differentiate the different workload demands of each class.

Some think the increasing number of AP classes offered to and taken by students over the years has fueled lower admissions rates at many prestigious universities across the nation. Although it may seem as if we as Paly students compete with ourselves to land in a college’s “quota” of acceptance letter recipients, this is greatly confounded by the inherent nature of students to apply to a greater number of colleges and by other secondary institutions’ desires to artificially inflate grades to subtly increase their students’ chances of getting into more prestigious universities.

Most universities add one grade point for an AP class a student takes. With the rising number of students taking these college-level classes, universities have instituted higher cutoff scores for those seeking transfer credit and more advanced lane placement. However, in order to verify that students enter college prepared with solid foundations of subjects, AP exam scores show colleges a student’s proficiency in a given discipline. Regardless of whether one must repeat an introductory class in college, it certainly doesn’t hurt to intellectually smooth the transition to college.

Finally, some find that AP curriculum overpressures teachers to teach only to the test and inadequately tests students on essential subjects. This is true to an extent, as teachers create assignments that involve previous AP questions or that tailor to the AP curriculum. However, just because a teacher teaches an AP class does not mean the only material covered in the class may be from an AP test prep book. At Paly, most teachers deviate from the set AP curriculum through labs, activities and other supplementary topics. In addition, for the most part, teachers sufficiently prepare students for AP tests with ample time to spare before the May test dates, as they often find ways to supplement AP review sessions not only during the weeks right before the test, but also all throughout the year.

But even for those who think the College Board’s expectations of knowledge of AP test material serve as an inaccurate representation of what students should learn from the courses, only permitting students to take a select number of APs does nothing to solve the problem at hand. Doing so sets the flawed precedent that students can’t take a more academically intensive course simply because the curriculum lacks competence in covering topics to the extent it ought to within a one year span. In such circumstances, the only beneficial means to solve such a problem would be to eliminate the AP program at Paly and allow students to choose accelerated courses from those available.

What this boils down to is an issue over who is in the position to tell a student what the limits of their intellectual capacity are. The answer is simple: definitely not the school administration.