[divider]Experiences with Reporting Sexual Misconduct in PAUSD[/divider]

“It’s like he still wins. Every day.”

Jamie, a current senior at Gunn High School who agreed to be interviewed only if her real name wasn’t used, said she constantly thinks about the lack of justice she received for her sexual assault in September 2019, her sophomore year. She said her boyfriend at the time manipulated her, sexually harassed and assaulted her, mocked her for years and then did it all over again to another girl in her grade.

His punishment? She said nothing more than a message sent home to his parents.

Jamie said she remembers sitting in her first period English class one morning in May 2019, crying about her abuser’s attempt to coerce her into not reporting her assault to school administrators. She said her teacher approached her and asked her what was wrong, and when he found out, he sent her to report her experience to the Title IX team at Gunn.

“When I was taken to the office, there was no one there,” Jamie said. “No vice principals were available. No principals were available and the counselors weren’t there. So (my teacher) took me to the Wellness Center, and I started talking to the woman there. Before I left, she told me she would call me back in that same week to finish reporting, but she never did.”

Jamie said her complaint wasn’t filed over the summer or investigated at all after that, so she re-reported her case in September of her junior year to Margaret Reynolds, Assistant Principal at Gunn at the time and current Paly Assistant Principal. While she explained her situation, Jamie said Reynolds kept asking her unrelated and inappropriate questions.

“When I started talking about my perpetrator and my physical relationship, she specifically asked me if I was a virgin when he assaulted me, and if he was one,” Jamie said. “She then asked me to describe what fingering was and other graphic sexual acts that were unrelated to my assault.”

Shocked, Jamie said she started crying during her conversation with Reynolds and asked her how the questions were relevant to her case.

“I was like, ‘Do I have to answer this?’ And she was like, ‘I mean, the stuff that you don’t answer will only make your case sound weaker,’” Jamie said.

After this meeting, Jamie said Reynolds issued a no-contact order between her and her assaulter, meaning they weren’t allowed to be near each other, even on the same side of the Gunn campus, and weren’t allowed to digitally contact each other.

However, Jamie said her perpetrator found a way to indirectly harass her through an anonymous confessions account on Instagram. Pretending to be Jamie, he submitted a post attempting to make it appear that she was confessing to lying about her assault.

“I instantly freaked out when I saw this, so I told my parents what had happened and they emailed Mrs. Reynolds, specifying that I did not write that post,” Jamie said. “And then she asked us, ‘How do you know your daughter didn’t write that post?’”

Reynolds said she could not comment on Jamie’s case because of the confidential nature of Title IX investigations.

Later in October of her junior year, Jamie met with Megan Farrell, PAUSD Title IX coordinator at the time, to officially investigate the case. Jamie said Farrell seemed distracted and more concerned about Jamie’s appearance than the case.

“I walked into the room and she scanned me up and down and said, ‘Oh my God, you look like a beautiful Italian model,’” Jamie said. “I was like, ‘What?’ When we actually started talking about my assault, I was crying. She stopped me and put her hand on my arm and was like, ‘It’s so hard to focus on what you’re saying while I’m watching your beautiful blue eyes tear up.’”

A few weeks after their meeting, Farrell released the results of her report, and Jamie was appalled. Despite her sharing several folders of screenshotted text conversations depicting her assaulter sexualizing her and manipulating her, the report claimed there was no solid proof to back up Jamie’s claims. Her perpetrator was not punished outside of a note sent home and a no-contact order, which Jamie said he violated several times.

“It makes me so mad,” Jamie said. “He just gets to live like normal and keeps spreading this narrative that I’m crazy.”

Farrell said she could also not comment on Jamie’s case because of the privacy laws governing Title IX investigations.

Starting high school in a brand new environment should have been the extent of Sarah’s troubles her freshman year — new friends, teachers and pressure to get good grades were already a lot to handle. To help the transition and to further her interest in computer science, Sarah joined the robotics team. Little did she know, her later alleged sexual assaulter would be on that team.

Sarah, a Paly junior who agreed to be interviewed only if her name were changed, said her perpetrator first started to sexually harass her in December 2018, making lewd and inappropriate comments about her body and describing sexual acts he wanted to do to her. Then, Sarah said her perpetrator began to pressure her into performing sexual acts and assaulted her on several occasions.

“He never took no for an answer and forcibly touched me in a sexual manner despite my physical and verbal protests,” Sarah said.

Sarah said he continued this behavior until March 2019, when her friends helped her cut off contact with her assaulter.

“During the assault, I felt trapped in a way,” Sarah said. “I wasn’t sure what to do or who to talk to, but eventually I told my friends and they supported and inspired me to report the case.”

In May 2019, Sarah said she decided to email proof of her assault to Assistant Principal Jerry Berkson to start the process of reporting her experience, including screenshots of her perpetrator harassing her over text. About a week later, Sarah said Berkson and then-Title IX officer Megan Farrell called her in to talk about her case.

Sarah said at the time, Berkson and Farrell offered her two different options: a formal one that involved reporting her case to the police and doing an official investigation, and an informal one, where a mediator would facilitate a conversation between Sarah and her perpetrator. Sarah said the formal option wasn’t an extreme she wanted to take, but she also wasn’t ready to confront her assaulter.

“I didn’t feel comfortable with the informal route, obviously,” Sarah said. “So I asked them, ‘Is there something in the middle that we can do?’ And they were like, ‘I don’t know. We’ll have to see.’”

In an effort to find an alternative solution to her case, Sarah said she requested her perpetrator receive an appropriate punishment, such as suspension from school, removal from the robotics team or removal from classes they had together. But because a similar case at Gunn High School utilized similar punishment and was unsuccessful in providing a resolution, Sarah said the administrators told her they had hesitations about administering what she was requesting.

“They were like, ‘We don’t really want to try that because it didn’t work out at Gunn,’” Sarah said. “And I understand their concern, but it was really disheartening to hear that, ‘Oh, just because it didn’t work before, we aren’t even going to try it with you.’ Somehow (the Gunn case) deemed mine a lost cause.”

Sarah said their hesitation and unwillingness to accommodate her requests, even those as small as removing him from her classes, made meetings with administrators uncomfortable and intimidating, and resulted in her constantly second-guessing herself and regretting reporting her assault.

“They made me feel like I shouldn’t be reporting it and that I was asking too much, or that the way that I wanted to guarantee my comfort and safety at the school was too much to ask for,” Sarah said. “It just seemed like coming in and talking to me was a burden to them, like my case was like, ‘Oh my God, not another thing to deal with.’”

Berkson said his aim isn’t to be insensitive or seem like he doesn’t want to help survivors with their case.

“As an investigator of cases, I don’t prejudge the situation and try to keep all biases out of the picture, so it may come off as me not caring, or unenthusiastic about a situation, but really I am a fact-finder in the initial phases of an investigation and need to work on the task at hand,” Berkson said.

When school ended last year, Sarah said Berkson and Farrell told her she would be kept in the loop about her case’s progress while Title IX officers worked on it over the summer, but that this promise fell short.

“There wasn’t a lot of communication over the summer, despite them saying that they would regularly update me and my parents on the case,” Sarah said.

Sarah said when she returned to school in August, it was almost as if nothing had changed since she reported her assault in May.

“It eventually got to the point where I felt like the district couldn’t do anything productive in terms of what I was asking for, so the case just kind of dropped,” Sarah said.

Sarah said the district didn’t do anything for her except call her perpetrator’s parents –– no restraining orders, no removal from the robotics team and no relief from having to see him in her classes. Sarah said her assaulter eventually quit the team when his teammates started to figure out what he had done, but the district did not play any role in this.

“Since then, I haven’t been able to look at myself the same and have constantly had to deal with the repercussions while he’s been able to live his life,” Sarah said.

Farrell said she could not comment on Sarah’s case because of privacy laws governing Title IX investigations. She left PAUSD in November of 2020 and now works as the Title IX coordinator for the Los Gatos-Saratoga Joint Union School District.

[divider]Sexual Harassment & Assault Culture[/divider]

PAUSD is affluent and top-ranked and may not be a school district that first comes to mind when thinking of an environment that enables sexual assault.

But junior Sophia Cummings said this is blissful ignorance. She said she is constantly reminded of how acceptable sexual harassment and assault are in the district.

“People are like, ‘Oh, yeah, like, I know you always have to get consent and stuff,’ but then they don’t think it applies to smaller things,” Cummings said. “It’s made it really difficult for some people to even just go to school, and it affects the way that girls want to dress and how they present themselves. And it makes it really hard to trust other students and enter relationships. I just think it’s really sad that you have to be worrying about that all the time.”

Cummings said she has faced facing several instances of sexual harassment on campus, including boys groping her legs and taking photos of her chest. She said after one instance, she went to the bathroom and cried.

“I was just shocked that it was someone who I thought was my friend, and they (seemed) to not be aware that they had just done something wrong,” Cummings said. “(And my friends), they always have some kind of similar story to tell me in return.”

Sarah, the Paly survivor, said people who choose to believe perpetrators rather than survivors continue to enable sexual assault and rape culture.

“People are more likely to be struck by lightning than to be falsely accused of rape and assault,” Sarah said. “If someone were to tell me that one of my closest friends had raped or assaulted someone, I would much rather believe the victim and show them support than to keep in communication with a criminal, with a rapist.”

Aside from some students at PAUSD perpetuating a culture that normalizes sexual assault, Jamie said having unsupportive friends and family compounds the issue. She said part of the reason she struggled so much with her sexual assault experience was the initial lack of support from people around her.

“When I told my friends about my sexual assault, they tried to convince me that nothing had happened and that I was basically just trying to find a reason to be mad at my ex,” Jamie said. “They told him that they felt sorry for him and that they wanted to help him, that they didn’t want me to ruin his life.”

She said one of the best ways to support victims of sexual harassment and assault is to believe them and talk with them about their experience.

“It’s just crazy when you realize there are actually people out there who don’t believe (survivors) or support them,” Jamie said. “(Support) would have made so much of a difference and made everything easier for me because it would have made me report faster.”

Junior class president Mathew Signorello-Katz said he thinks showing support for survivors is crucial to making students feel comfortable and safe at school. He said not enough male students extended their support on social media in January, when several survivors came forward with their stories on social media and sparked a widespread discussion on sexual misconduct within PAUSD.

“I was extraordinarily disappointed to see that a lot of my fellow male classmates at Paly weren’t really speaking up about it and were just remaining silent,” Signorello-Katz said. “I think silence and complacency are so incredibly dangerous in so many ways … People who feel as though Title IX-related matters don’t apply directly to them and see it as something that they don’t need to become involved with (are) how you continue to perpetuate rape culture at Paly, Palo Alto and beyond.”

[divider]Moving Forward[/divider]

Understanding the prevalence of sexual misconduct in the district is one thing, but fixing it is another. Jamie, who helped start a support club at Gunn for survivors of sexual harassment and assualt, said one of the biggest problems in the district is the administration’s approach. Jamie said instead of doing what they can to protect students, administrators try to protect the reputations of the district and the alleged assaulters.

“Instead of trying to prevent Title IX cases from happening by making it seem like nothing is happening, they should disincentivize people from violating, meaning actually hold perpetrators accountable,” Jamie said. “They taught my abuser that (his actions) were OK, and that he can get away with it.”

Kelly Gallagher, the new Title IX coordinator for PAUSD since January 2021, said the standard is to use a system based on preponderance of evidence to determine the course of action.

“We are looking at, ‘Do we have enough information to say it is more likely than not this occurred, as in 50% or more?’” Gallagher said. “And if the answer is yes, then that person is responsible for a violation.”

For Sarah, there are a lot of ways the PAUSD Title IX team can improve, including implementing better sensitivity training for administrators and making the process more transparent and accessible. She said poor communication was a big reason she had a negative experience in reporting her case. She also said the district needs to contact survivors throughout the reporting process.

“Even if not much is happening –– even if there haven’t been any major developments and things are still in the works –– I think it’s important to let (the survivor) know what’s going on,” Sarah said. “Because at least they’re not in the dark.”

Junior Site Council Representative Nysa Bhat said the Associated Student Body at Paly is working to help prevent incidents of sexual assault and harassment by creating a Title IX sexual violence task force and partnering with Paly clubs RISE and Bring Change to Mind to provide resources.

“We need change and we need it now,” Bhat said. “ASB has created a dynamic task force that will work in tandem with the Paly administration to communicate what the needs of the students are in regards to the change of Title IX policy that seemingly only protects perpetrators, as well as changing the tolerance of a culture that promotes sexual violence at Paly … This is by no means a cure-all, but rather a small step that we can take as ASB in helping to invoke true, lasting change at Paly and beyond.”

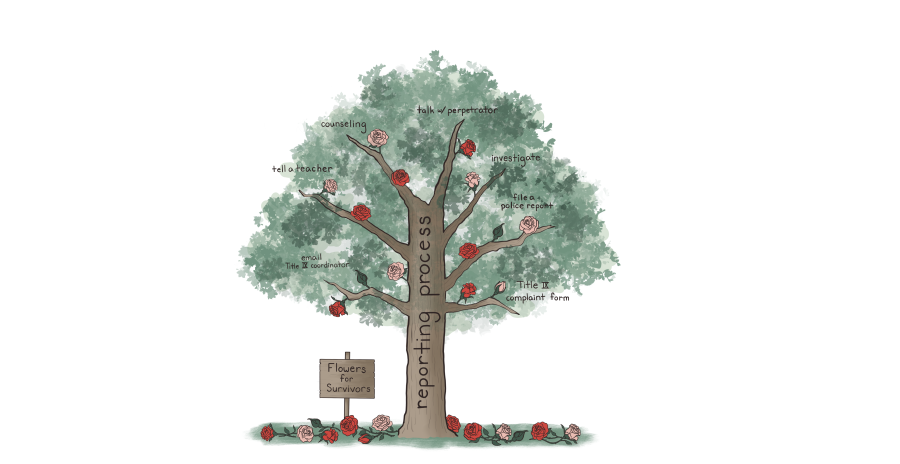

Cummings, who said she didn’t report her own sexual harassment to administrators out of fear of escalating the situation, said it would be beneficial to students if administrators were more transparent about the Title IX process.

“The whole process is super unknown –– I have no idea what it would look like and what would happen,” Cummings said. “I think that’s really intimidating for a lot of people, and that’s why they kind of steer away from doing anything about it.”

Cummings said it’s important to demonstrate sensitivity, patience, and empathy while providing support to victims.

“After you’re violated in some way, you feel this huge lack of strength and a loss of dignity and self-confidence,” Cummings said. “Just having people –– sometimes it’s not even people that you know –– show that they support you, that they believe you, they’re listening to you and they’re trying to understand like what you’ve gone through, helps give you that strength.”

Correction on 3/26: “Preponderance of truth” was changed to “preponderance of evidence” to more accurately reflect legal terminology used in Title IX investigations.