Flower bouquets, candles and objects that represented senior Lauren Brierly covered the folding tables on Los Altos High School’s quad on April 4. A poster with hand-written messages dedicated to Brierly stood adjacent.

Brierly died on the morning of April 1 following what is being investigated by Mountain View Police as a possible fentanyl overdose. She was 18 years old.

Pinewood School senior Rachel Farhoudi, who played soccer with Brierly on the Mountain View Los Altos club soccer team, said Brierly was a role model to her younger teammates.

“She didn’t have a mean bone in her body,” Farhoudi said. “She was just the nicest to everyone and got along with everybody.”

Farhoudi said Brierly’s death was a huge wake up call for the Los Altos High School community.

“Lauren was the last person I would expect this to happen to,” Farhoudi said. “I mean, you never expect it to happen to anyone, but it was definitely a shock.”

Fentanyl-related deaths are rapidly increasing in Santa Clara County: the synthetic opioid 50 times more potent than heroin killed 27 people in 2019, 86 in 2020 and 132 in 2021, according to the Santa Clara Medical Examiner-Coroner’s office. Seemingly overnight, fentanyl has become the leading cause of death among Americans aged 18-45, surpassing suicide and COVID-19.

David Fisher, the Crimes Against Persons sergeant in the detective bureau for the Mountain View Police Department, oversees the detective unit which handles any crime that has a human victim. His unit is currently involved in the open investigation into Brierly’s death and waiting on the toxicology report. While he is unable to comment on the case, he said he has seen a general increase in fentanyl poisoning from people who unknowingly consume fentanyl-laced drugs.

“For teenagers specifically, I hope that this is a little bit of a sobering event because it’s very scary,” Fisher said. “There’s a potential that just buying a pill of Adderall could have fentanyl in it, and that could be the last thing you do.”

Surge in opioid prescriptions leads to fentanyl crisis

In the ‘90s, doctors began prescribing more opioids to patients for minor and chronic pain conditions, Stanford Professor of Addiction Medicine Anna Lembke said. When prescriptions started to decrease by 2012, it was too late for many patients.

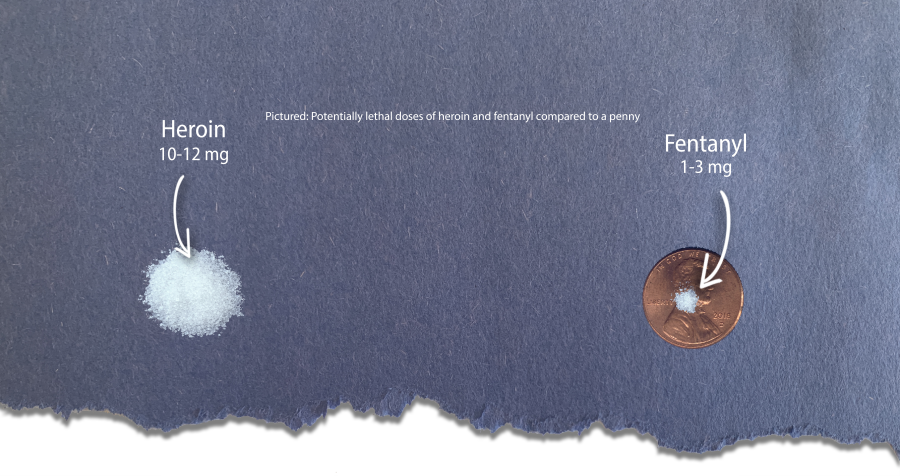

“People who had become addicted at that point then turned to cheaper and more abundant sources like illicit opioids like heroin and illicit fentanyl,” Lembke said. “And fentanyl is much more potent: it’s 50 to 100 times more potent than (other powerful opioids like) heroin or morphine.”

In addition to its potency, another reason illicit producers use fentanyl is because of its cheap, synthetic nature, Lembke said.

“For thousands of years, people have used opioids derived from the poppy plant or opium,” Lembke said. “In the last hundred years, scientists have figured out how to synthesize fentanyl and other opioids in a laboratory without needing the plant. You don’t need to cultivate it, you don’t need to harvest it, you don’t need to ship it, you just need the precursor chemicals. So fentanyl is really cheap to make.”

Lembke said when illegal drug manufacturers realized fentanyl’s profitability, they started to put fentanyl in other opioids, such as heroin, effectively cutting costs while giving their customers a more intense and addictive experience. In addition, fentanyl’s potency can cause customers to return, seeking out the same addictive effect.

“If you have some heroin, and you want to make it a little bit stronger so that your customers get an effect and come back to you, then you would put a little bit of fentanyl in there,” Lembke said. “But it’s then hard to gauge how much somebody can tolerate.”

Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen said there has definitely been an increase in fentanyl in Santa Clara County and in the state.

“Several years ago fentanyl was more prevalent in the East Coast and the Midwest of this country,” Rosen said. “And then a few years ago, it made its way to California. Initially, fentanyl was coming here from Mexico and now it’s coming from China. It’s very inexpensive for drug dealers to get it and it’s highly dangerous.”

Today, the practice of lacing other drugs with fentanyl is so widespread that nearly any drug purchased illegally is at risk of being contaminated with fentanyl –– even some forms of marijuana. Just two to three milligrams of fentanyl can be fatal to someone with no preexisting opioid addiction.

But there is hope. Lembke said the distribution of Naloxone, an opioid overdose reversal agent marketed under the brand name Narcan, has lowered opioid overdose deaths.

“Naloxone has been made widely available in the city of San Francisco since approximately 2008,” Lembke said. “And we think as a result, the heroin-related overdose deaths in San Francisco remain lower than in other regions.”

Regardless, she said she said students should be extremely cautious when taking any drug.

“Don’t ever take a pill that wasn’t prescribed to you by your doctor and obtained from a pharmacy,” Lembke said.

Students grapple with risks of substance use

In December 1997, a then-Paly senior was anonymously quoted in The Campanile, saying, “Getting drugs at Paly is easier than water-ballooning a freshman.” A survey of 362 Paly students from the week of Dec. 1, 1997, also found that of those polled, 42.3% admitted to having used an illegal drug at least once. Back then, alcohol was the illegal drug of choice, followed by tobacco and marijuana. Today, according to the National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics, 10.37% of Californian 12 to 17-year-olds reported using drugs in the past month, with alcohol and marijuana being the most commonly used drugs among teens nationwide. Paly is no exception to these statistics.

A Paly senior who agreed to be interviewed only if her name was not used said the majority of people she knows have either done drugs or regularly use them. In fact, she said the economic status and competitive environment of the school and community may contribute to this drug use.

“We live in this area with so much wealth … either the kid feels so much pressure from their parents that they choose to find something like cocaine to study and to work harder, or they’ll do something to cope,” she said. “They might try something like opiates and see if that’ll have any effect on how they feel.”

Paly 2021 alumni and Colorado University at Boulder freshman Benny McShea said fentanyl is a large problem amongst the Boulder student body, specifically when put into cocaine without the knowledge of the user.

“I just remember first hearing from social media posts, and parents groups on Facebook how people should tell their kids to stay away from cocaine, especially since it could be laced (with fentanyl),” McShea said. “And in the first week, three freshmen died.”

In response to the current fentanyl crisis, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends the use of fentanyl testing strips for drugs, since it is nearly impossible to tell if drugs have been laced with fentanyl without them. McShea said other colleges allow students to request drug tests to make sure their substances are not laced.

“It’s completely free, completely anonymous,” McShea said. “Receive a little package and you get to test whatever, marijuana, psychedelic, whatever you’re doing. You get to test it and see if it’s safe or if it’s not.”

McShea said students can be placed in situations where they may take dangerous drugs at the moment without considering the consequences.

“If you’re at a frat party and you’re drunk going around and someone offers you cocaine, right at that moment, you might just say yes to doing it, even though you don’t have the opportunity to test it beforehand,” McShea said.

And the anonymous Paly senior said people who experiment with drugs should be cautious when dealing with illicit drugs that are at risk of being laced with opioids like fentanyl.

“What I like to say is, ‘If you’re going to do something stupid, do it in the smartest way possible,’ because everyone does stupid s—,” she said. “But it’s about harm reduction. It’s about minimizing risk. It’s about having fun but not dying (while) doing it.”

Local task force fights fentanyl epidemic

The 132 people killed by fentanyl poisoning last year in Santa Clara County defy stereotypes held about drug users: they include both poor people and rich people, people of all ethnicities, genders and ages. Fentanyl is being laced into an increasing amount of drugs bought from illicit sources, creating a lethal high for people who may not be aware of fentanyl in the drugs they take. Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen said opioid abuse, which includes the use of fentanyl, is the leading cause of drug-related deaths in Santa Clara County and the leading cause of death for people under the age of 25 in the county.

In response to the rising number of fentanyl-related deaths in the county, The Santa Clara County Fentanyl Task Force held its first meeting on Zoom in April. The task force is made up of individuals from law enforcement, crime units, behavioral health, medicine, local government and schools; people who study addiction, have been addicted to drugs, and were friends and family of those who died from fentanyl poisoning. Among many topics, the group discussed fentanyl’s circulation, detection and origins, and the distribution of overdose prevention tools.

On the criminal justice side of overdose prevention, law enforcement is on alert. Rosen said two people are currently being tried for murder through selling fentanyl laced substances and several have been prosecuted for the felony of violating Santa Clara County’s health and safety code through selling the equivalent of poison.

“(We) recently arrested a man who had 11,000 fentanyl pills in his car,” Rosen said at the meeting. “So let’s put that into perspective. The 12-year-old girl who died went into cardiac arrest within minutes after ingesting just part of one pill. Traditional law enforcement approaches can still work, but we also must evolve. Drugs are a health problem. Addiction is a sickness. We will not arrest and prosecute our way out of this crisis.”

On the public health approach to overdose prevention, the task force is looking into establishing a fentanyl advisory which informs people of personal and legal consequences of using fentanyl. Task force member and San Jose State University professor Erin Woodhead said another strategy the task force is using includes raising awareness among younger potential users.

“The communications committee is going to try to address how we can effectively reach teens with information in a way that they’re going to listen and not feel we’re just lecturing them,” Woodhead said. “We’re also trying to incorporate some younger people into this working group to really understand their mindset.”

Woodhead said that information has to be presented in a specific way to be successful in deterring teens away from drugs.

“You need to give both sides of the information,” Woodhead said. “You’re giving both the consequences of use and you’re acknowledging why it may feel good for a teen to use that drug. That’s part of (teen) development — understanding new experiences and expanding their view of the world.”

Another strategy the task force is using includes overdose reversal kits and testing strips. Mountain View Police Department (MVPD) sergeant David Fisher said all police officers carry Narcan kits with them so that they can quickly reverse an overdose. Fisher said the MVPD used to have drug testing kits, but like many other police departments, they generally do not use them anymore because potential exposure to fentanyl can be deadly. Samples of substances police collect are instead sent to labs to be tested.

But while police generally do not test substances, fentanyl test strips are cost-efficient and effective, and Woodhead said the task force is currently acquiring them to spread throughout local communities.

“These strips would allow people to determine if the drug that they’re about to take has any amount of fentanyl in it,” Woodhead said. “They’re relatively inexpensive. It is an action we can take pretty quickly that isn’t going to cost a lot of money.”

Despite these efforts that have decreased the rates of overdose, Fisher said he thinks the problem will continue. He said producing and selling fentanyl-laced substances generate profit, so it is especially important to stem demand as well as supply by making sure people are aware of the dangers of fentanyl being laced into any substance not bought directly from a pharmacy. Rosen agreed.

“It’s not like when you go to the pharmacy and you know if you’re buying Advil, you’re getting Advil, or Tylenol, you’re getting Tylenol,” Rosen said. “When a drug dealer gives you a pill and tells you it’s Xanax or Sudafed, or Vicodin or Percocet, it might be. It might also have fentanyl in it which could kill you. So if you need medication because you’re in pain, talk to your doctor and get a prescription from your doctor, but don’t try to self-medicate by buying from somebody where you have no idea what they’re selling.”