Palo Alto Unified School District appears to have too many students of color in its special education program relative to its overall student population, according to a new state study. Among the proposals to remedy the imbalance: identify students sooner who might have learning disabilities such as dyslexia.

Recently released findings from the California Department of Education, which cite a disproportionately large number of students of color in the district’s special education program, may indicate underlying issues of systemic inequity and overidentification of minorities. Generally, disabilities would spread proportionately across all races, but PAUSD’s disability population is not, thus catching the attention of the state.

PAUSD Superintendent Don Austin explained that overidentification is jumping too quickly to identify minorities, disregarding the gradual steps taken to ensure proper classification. Austin said that plans are underway to find potential solutions to these over identifications.

“If something like dyslexia isn’t properly identified early, it could easily turn into an inappropriate special education identification, so by us trying to (screen children for dyslexia) earlier and find out the strategies for their learning, then we can help someone with dyslexia be more successful,” Austin said. “That’s a place where we can reduce future classifications in special education.”

In the 2017-2018 review conducted by the CDE, PAUSD was found to be non-compliant in its disproportionate number of African-American and Hispanic students classified as having a Specific Learning Disability.

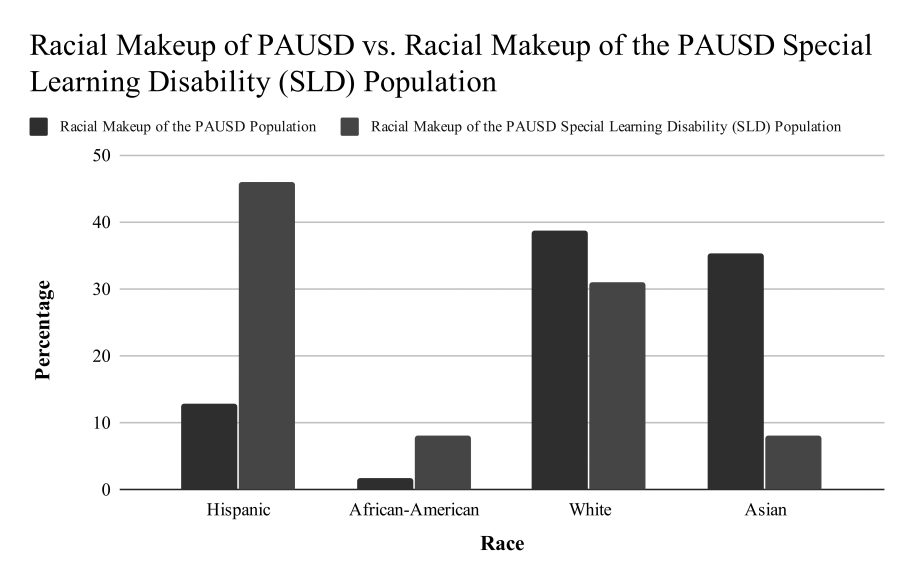

The CDE found PAUSD’s K-12 Specific Learning Disability population of 340 students consisted of roughly 46% Hispanic students, 31% White students, 8% African American students, 8% Asian students and 8% who identified as Multiracial. This compares to PAUSD’s racial makeup in 2017 of 38.6% White, 35.4% Asian, 12.9% Hispanic and 1.7% African American.

The CDE predicts PAUSD will be labeled as “significantly disproportionate” for three consecutive disproportional years, including the 2018-19 school year. PAUSD would then, hypothetically, have to direct 15% of its Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) funds toward programs aimed at reducing the apparent problem of the mentioned disproportionalities.

PAUSD aims to use part of these funds toward Goalbook, thereby ensuring that there are processes and programs implemented to mitigate the disproportionalities. Goalbook is a service that helps digitize goals for students in special education and streamlines relationships between teachers and their students to better track their progress. All special education teachers were recently introduced to the program during a board meeting, and Austin said they were “all overwhelmingly enthusiastic supporters of Goalbook.”

In order to help prevent too-frequent identification, Austin is implementing screenings for dyslexia, the most common specific learning disability, for students starting in elementary school. This is all in hopes of making sure that students’ disabilities don’t snowball, potentially causing them to be over-identified or misidentified in the future.

Despite Austin’s efforts, Tara Ford, a clinical supervising attorney for the Youth and Education Law Project at Stanford Law School and a policy advisor for the special education advocacy group the Community Advisory Committee, said she is particularly concerned about how PAUSD identifies students with disabilities and the intervention strategies for other specific learning disabilities besides dyslexia.

“Too often what happens is that, in special education, we wait for kids to fail before we provide the interventions that they need,” Ford said. “It’s an important mechanism to make sure that kids get the interventions they need in a timely and targeted way and that (PAUSD) look hard early.”

Ford said PAUSD’s processes of identifying disabilities are sometimes inaccurate, causing a misrepresentation in identifying disabilities — whether that be over-identification, under-identification or misidentification. Following the labeling of a disability, whether incorrect or not, Ford said that students face difficulties, often hindering their opportunities and overall mental state.

“One of the things that Congress has recognized for students with disabilities, which I think is true for historically underrepresented students as well, is those (negative) assumptions and low expectations impede success,” Ford said.

When Austin was asked for a comment, he responded that Ford is entitled to her opinion.

Additionally, Kimberly Eng-Lee, the chair of the Community Advisory Committee, noted there are factors potentially limiting minorities’ potential for growth and their relation to over-identification in special education.

“To some extent, I think (suggested over-identification of Hispanics) could be related to literacy and how they might’ve not been exposed to many words or, conceptually, whether those families have a different outlook on education,” Eng-Lee said. “One of our board members, Lana Conaway, said, ‘As a school district, we’re only as good as our poorest kids.’ Because families who can afford to get extra help don’t reflect the district’s capabilities.”

Eng-Lee explained that prior trauma can also impact a student’s performance in school because social and emotional trauma often disengages students from being mentally present and in a space where they’re eager to learn. Consequently, students facing trauma are commonly classified as disabled due to their supposed inability to learn in a general education environment.

“There’s trauma that students are facing that you and I can’t even begin to comprehend,” Eng-Lee said. “You know, I’ve seen families living on El Camino Real in a trailer. We don’t know how traumatic a family’s living situation is or having to come to school and then be expected to be a learner like everyone else. Whether that impacts their stress or their ability to learn then they need more than academic support; they need social-emotional support.”

Eng-Lee is proud of the district’s accomplishments thus far but notes that there’s still work necessary to ensure equity within education as a whole.

“The CAC is advocating that, regardless of the color of someone’s skin or their socioeconomic status, if it’s a student that needs help, we want to be sure they’re getting the right kind of help,” Eng-Lee said. “If underrepresented students in special education don’t have to be in specialized classes, then they shouldn’t be if it’s not going to be effective. Why spend anyone’s time teaching or sitting in a classroom if it’s not going to make a difference.”

Austin said he and the special education department are planning additional services that would help with addressing the issue to accommodate all students’ needs.

“Our whole special education department is working on this right now and will bring back a proposal which will go in front of the board of education which will be very specific,” Austin said. “We’re looking at better instructional practices that hit the majority of students.”