A high school student in Shanghai sits down to begin her homework. Her task? To write an 800-word apology letter for speaking Shanghainese, her local dialect, in class.

According to the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission, the Chinese government banned Shanghainese from the education system in 1992 in an effort to unify China in speaking one common language: Mandarin.

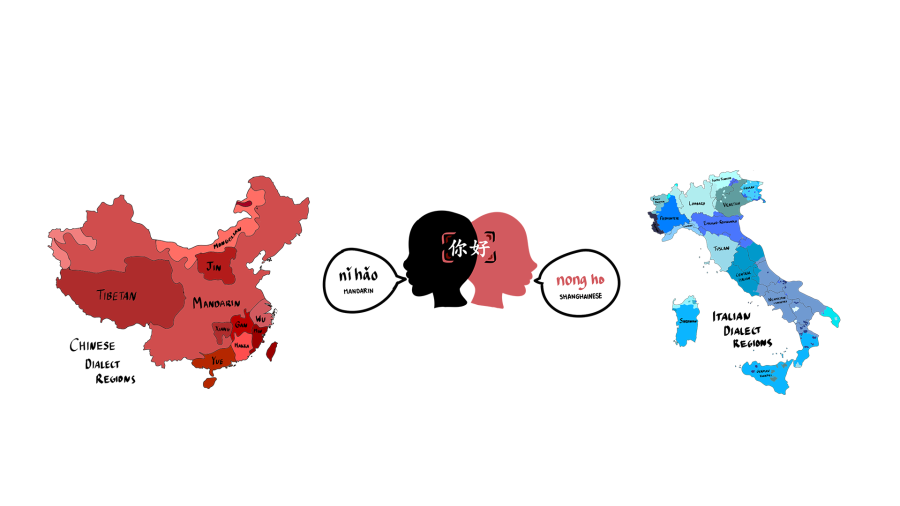

Dialects are spoken vernacular codes with no standard written system, and they exist in almost every major language, from Chinese to Italian. In some nations, speaking a dialect represents a connection to local culture, but in others, it represents national disunity and a lack of proper education.

[divider]Shanghainese[/divider]

There are eight main spoken dialect groups within China, and most are mutually unintelligible. Shanghainese belongs to the Wu dialect, and Paly junior Jasper Wang grew up speaking it.

“My family largely only spoke Shanghainese,” Wang said. “It felt most comfortable for me to learn Shanghainese by just striking up regular conversations with my grandparents because they don’t speak Mandarin too well, so it’s the only way that I can converse with them.”

Paly Chinese teacher Liyuan He said the main differences between Shanghainese and Mandarin lie in speaking speed and intonation.

“Compared to Mandarin, Shanghainese is spoken at a particularly fast pace,” He said. “Shanghainese also incorporates retroflex consonants, where the tongue has a curled or flat shape, which Mandarin does not.”

Fourteen million people currently speak the dialect, but that number has been on the decline in recent years, according to Paly Chinese teacher Jing Xu.

In 2016, the Shanghai Institute of Finance and Law conducted a study in which 2000 native Shanghai adults were surveyed randomly on the streets of Shanghai. The results showed that those born before 1992, the year Shanghainese was banned from schools, were mostly or completely fluent in Shanghainese, while the number of fluent speakers born after 1992 exponentially decreased as age decreased, with over 30% reporting inability to fluently speak it.

Oufan Zhang, a 22-year-old Shanghai native, was born after the ban was enacted and was strongly discouraged from speaking Shanghainese in class throughout grade school.

“We wouldn’t talk to each other in Shanghainese because we were taught in Mandarin at school,” Zhang said. “If your friend didn’t get exposed to the dialogue at home, they wouldn’t understand the dialect.”

As a result of discouragement from speaking the dialect in school, Zhang does not speak the dialect very well, though she has picked it up loosely from observing her family.

“(My parents’ generation) speaks the language — we don’t do that anymore,” Zhang said.

Xu attributes the decline in the dialect’s popularity in part to increased immigration to the city.

“There are a lot of people who were not born in Shanghai, but go to school in Shanghai and then stay and work there,” Xu said. “Because there are so many people who live in Shanghai and are not originally Shanghainese, more people speak Mandarin. I think there are less and less people actually speaking Shanghainese — even two young Shanghainese people speak Mandarin to each other.”

However, according to the Shanghai Ministry of Education, the city of Shanghai began making efforts to preserve the dialect starting in 2011, when the government began a two-year project to create a nationwide vocal database of local dialects across China.

“The recent trend is that people have started thinking about cultural conservation, and they believe that language is a part of culture,” Zhang said. “They don’t want the culture to die so they are trying to teach Shanghainese in school, but we didn’t do that when I was in school.”

For the city’s dialect preservation project, only two of the 13 recruitment sites were able to find “pure” speakers of the dialect, according to CNN. Despite efforts by individual families and schools, there has been no evidence of a measurable increase in the usage of Shanghainese among the youth, and fewer children than ever know how to speak the ancient dialect, according to the same Shanghai Institute of Finance and Law study.

In order to preserve the dialect, both Xu and Jing suggested teaching Shanghainese in classes while also encouraging parents to speak to their children in Shanghainese. Xu added that exposure to the dialect through popular culture and television shows would also help keep the dialect in use.

[divider]Southern Italian[/divider]

Dante Malagrino grew up in the southern Italian province of Puglia, where locals speak distinct regional dialects. According to him, there are several major Italian dialects like the Neapolitan, Sicilian and Tuscan dialects, along with dozens of smaller dialects as a result of Italy’s relatively recent unification.

“Italy has always been divided into very small states that are very different from each other, so each one of them has developed a variation of the language,” Malagrino said. “Italy is in a position in the Mediterranean that made it subject to a lot of invasion, so in the dialect I speak, for example, a lot of words come from the Arab language, from Turkish, from Spanish, from French … and the root of the language is actually Greek, because that part of Italy was a Greek colony.”

Malagrino speaks the dialect of Taranto, the town where he was born, and the dialect of Bari, the town in which he attended elementary and middle school.

“There’s no formal education that teaches you how to speak a dialect,” Malagrino said. “It’s just learned by speaking with other people and listening to people and every time, you pick up a new word or a new way of saying things — and that’s how you learn.”

Senior Marco Simeone, Malagrino’s nephew, grew up in another southern Italian town called Martina Franca — according to him, his dialect has heavy French influences, as the French colonized the area in the 14th century. Simeone said he does not speak the dialect well since he did not have a relative to learn it from, but many of his friends do.

“Most of (my friends) learned (how to speak the dialect) from their grandparents, and some of them from their parents, but it’s always less common to find middle-aged people that can speak dialect properly,” Simeone said. “It’s much more common to see elderly people (aged) 60-70 speak dialect daily.”

According to Simeone, the dialect is not very popular among younger people in his town, and is primarily spoken by the older generation. However, Simeone believes the dialect is an important part of his culture.

“It’s part of our history, it’s part of the (history of the) population that colonized and developed our cities,” Simeone said. “It’s something to be preserved, but unfortunately that is not what is happening — it’s a language that we are losing constantly every day.”

Simeone said rather than speaking in dialect regularly, his friends will sometimes use it to express certain feelings.

“My generation in Italy knows that there’s a deep connection between (the dialect and) their childhood, their tradition and the city they’re living in,” Simeone said. “They consider (dialect) a pretty important aspect of their life, but they don’t do anything to preserve it.”

To preserve the dialect for future generations, Simeone said it ought to be taught in history classes. According to Simeone, this would help new generations understand the importance of the dialect and keep it from becoming obsolete.

Conversely, Malagrino said that in the small town he grew up in, the dialect has maintained much of its popularity. According to Malagrino, dialect is almost seen as the official language in some southern Italian towns such as Campagna and Sicily, and is an important part of the regional culture. It is celebrated through performances, theater shows and contemporary music which incorporates a mix of Italian and local dialect.

“When I was young, the people who spoke dialect were the poor people, the ignorant people, the ones that didn’t have a chance to study, so you had to speak Italian to show that you were above the masses,” Malagrino said. “I think people are rediscovering dialects because instead of dialects being seen as a show of ignorance, now dialects are seen as a show of connection with (one’s) roots and culture.”