Every fall, millions of high school seniors sit down at their computers and attempt to boil their life’s journey into a 650-word essay. Their application, which consists of transcripts soaked in sweat, years of hard work, scores on standardized tests, lists of activities and seemingly endless paragraphs that hope to capture their personality, will decide their fate in the cutthroat, highly competitive college admissions process.

This year’s graduating class had to do even more amid a pandemic.

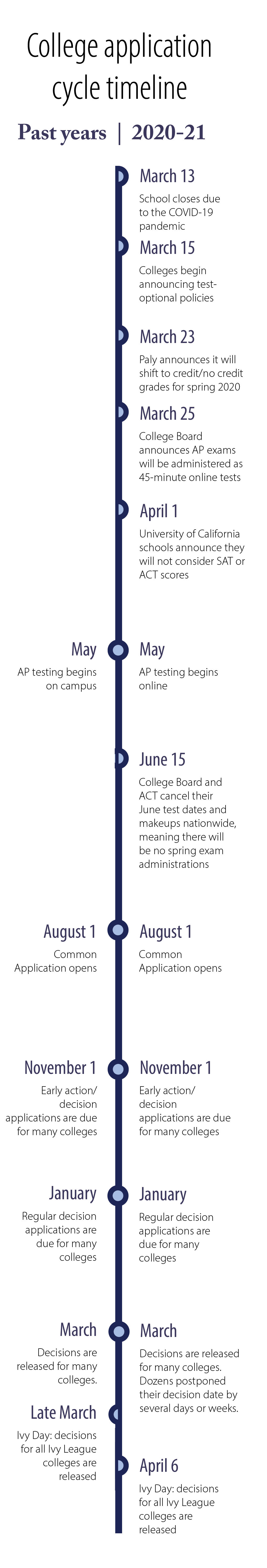

Faced with unprecedented changes such as the fear and uncertainty about safety during a pandemic, the abrupt transition to credit/no credit grading in the spring semester of their junior year, mad dashes for standardized testing spots and subsequent testing policy changes, distance learning, virtual counselor meetings, lack of social interaction and social and political unrest across the globe, the already stressful process of applying to colleges had never been more daunting.

[divider]College map trauma at Paly[/divider]

The Campanile Post-Paly Plans Map, a compilation whose initial purpose was to gather data on where the graduating senior class would attend college, was intended to be used as a resource and a celebration of the class’s accomplishments. Instead, according to the 2018-19 Campanile editors-in-chief, it perpetuated a toxic, comparison-driven culture at Paly.

The Campanile Post-Paly Plans Map, a compilation whose initial purpose was to gather data on where the graduating senior class would attend college, was intended to be used as a resource and a celebration of the class’s accomplishments. Instead, according to the 2018-19 Campanile editors-in-chief, it perpetuated a toxic, comparison-driven culture at Paly.

The map ran as “The Campanile’s Annual College Map” from at least the 1980s until 2016 and as the “Post-Paly Plans map” in 2017 and 2018.

According to 2017-18 Campanile editor-in-chief and Paly alumna Maya Homan, data gathering for the map began one month before the paper went to print and consisted of a Google form distributed to the senior class through the class Facebook group, on-campus flyers and word of mouth.

In 2018, the form garnered upwards of 400 responses, about 90% of the class. Homan said the editors even approached stragglers on campus to ask them to fill out the form as the publication date neared.

“It was a lot of just walking up to people in person and being like, ‘Hey, I noticed that you didn’t help us out. Would you be interested in doing so?’” Homan said. “It was kind of controversial at the time, and there were a few students who said ‘No, I’m not interested’ and we tried to be very respectful of that. But there were a couple of people who were like, ‘Oh, I’m not going to a four-year college, so I didn’t think that there was a place for me there.’ We tried to let them know they could still be included even if they weren’t planning on going to a four year college.”

Homan said the map was a valuable resource for the community, especially for underclassmen.

“A couple friends of mine used it as a way to look at where other Paly grads have applied, either just to know that was a place other Paly students have gone to or just to know who to reach out to when they were considering applying to different schools,” Homan said. “In the years since I’ve graduated, it’s been nice to look back to and kind of remember where everyone that I graduated with is now.”

However, both Homan and Paly College Advisor Sandra Cernobori agree the map and the community’s use of it were flawed. Cernobori said an inherent issue with the map was its lack of context.

“I think when you’re just looking at names and colleges without context, there are assumptions that are made that are not always accurate,” Cernobori said. “When people decide where to matriculate, all kinds of things influence that decision. It doesn’t mean you weren’t admitted somewhere else. For some students, money is a huge factor. Without context, I think (the map) wasn’t great — it reinforced unhealthy conversations and notions about success.”

Homan said another issue was the way the Paly community used the map to compare students.

“There were arguments that it added to this whole competitive atmosphere or harmed people who either couldn’t afford to go to a four year college or just didn’t want to or weren’t able to for whatever reason, and I think there was a valid argument behind that,” Homan said. “People used the name of their school as a way to display their status. That’s what the map became. I think if the (Paly) culture was less academically motivated, the map wouldn’t have been as harmful as it ended up being.”

In 2019, then editors-in-chief and Leyton Ho, Waverly Long, Kaylie Nguyen, Ethan Nissim and Ujwal Srivastava decided not to publish the map, even after spending several weeks gathering data.

“Our community fosters a college-centric mindset which erodes one’s sense of value and can lead to students with less traditional plans feeling judged, embarrassed or underrepresented,” the 2018-19 editors wrote in a statement addressing their decision that was published in May 2019. “We believe the burden of improving Paly’s environment falls on the students. If we don’t shift how we talk and think about college, the culture will never improve. This is the reason we decided not to publish the map this year.”

In its place, a series of quotes from Paly community members on the post-graduation culture at Paly were published. The map has not run in any subsequent years.

“We hope this decision sparks discussion about the values and priorities of students, families and community members,” the 2018-19 editors’ statement read. “We wish the best for every graduating Paly student in pursuing their future goals.”

[divider]College costs skyrocket[/divider]

Over the past 20 years, the number of college students utilizing financial aid in America has increased nearly 19%. Many claim this growing reliance for financial help is a direct result of annually increasing tuition rates.

Even during the pandemic, when many Americans were put out of work, institutions such as Stanford, Yale, Brown, Rice and Amherst all raised tuition prices by roughly 5%, according to CNBC. These increases in admission costs did not result in any added benefits for students as the pandemic forced colleges to move courses online. Despite shifting operations online and offering none of the in-person perks a student would expect when spending hard-earned money on tuition, these colleges decided to make their students spend much more for much less.

As campuses across the country continue to roll out plans to open up for the 2021-22 school year, the need for financial aid continues to rise. According to EducationData, the number of students receiving financial aid has increased from 83% in 2015-16 to 86.4% in 2019-20. The average growth each year during the past 20 years is 0.9%, and today, more students rely on some sort of financial aid than at any other time in history.

According to the U.S Department of Education, the price of tuition for public colleges has increased by an average of 6.5% each year over the past decade. These institutions continue to raise prices regardless of whether or not the public can afford it, and because of this, the public becomes more reliant on external sources and less independent. Unless tuition rates decrease, experts say over 90% of college students will need financial assistance.

[divider]Unprecedented testing policy[/divider]

As the competition to be admitted to a selective university increases with a growing applicant pool every year, the pressure on students to perform well academically is at an all-time high. Though there are multiple aspects to an application that colleges consider when practicing holistic review, one of the most common factors used to gauge student performance is standardized testing.

But when testing centers for the SAT and ACT began to close in March of last year, students across the country were left feeling their applications were incomplete due to their missing test scores.

According to Paly college advisor Janet Cochrane, most universities adopted test optional policies this year to prioritize student health over admission requirements and to be fair to students who were unable to test.

“Due to the continued difficulty of finding test seats, most of the colleges that adopted test optional policies for the Class of 2021 have extended that policy for the Class of 2022,” Cochrane said. “There are a few that have not officially announced that they will extend to 2022, but it is expected that most of them will. The remaining exceptions are still Florida public colleges, military academies and now Georgia public colleges have announced they will require test scores for the Class of 2022.”

Cochrane said because of the limited data released regarding 2021 admissions, it’s unclear yet whether or not students who submitted scores had an advantage over those who didn’t.

“It’s not entirely clear yet, but from the limited data released so far, there were a few highly selective colleges, such as the University of Pennsylvania and Georgetown University, that appeared to favor applicants that submitted test scores,” Cochrane said. “However, it may be coincidental that students who had and submitted high test scores were also top students academically.”

[divider]Hopeful recruits had to adapt[/divider]

As students navigated the transition to online learning during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, athletes attempting to get recruited to play on college teams faced additional challenges in an already convoluted process.

Junior Sebastian Chancellor said his efforts to get recruited for basketball were temporarily stymied by the onset of the pandemic.

In a normal year, the recruiting process typically begins with film or showcases. Athletes will typically reach out to coaches and ask them to take a look at video from their games to see how they perform. Athletes can also attend showcases to play in front of college scouts and coaches. If a coach likes the athlete, they might send scouts to watch their games or invite them to visit the college to meet in-person.

“During this COVID-19 era, it’s much more difficult to first get your film out there,” Chancellor said. “When you have such a small sample size (of game footage) that you can send to coaches, it becomes a lot more difficult for them to be able to watch your stuff and be able to see exactly what you can do.”

Chancellor said recruiting for basketball often runs through Amateur Athletic Union teams. However, travel restrictions limited the number of tournaments, and even then, coaches and scouts weren’t allowed to watch in-person.

“I tried to take the abroad route, and I moved over to Denmark first semester where they had full basketball,” Chancellor said. “I was able to send game film through being able to play, except over here (in the U.S.) where nobody can do anything, it’s really hard to be able to get film out there (to scouts).”

Basketball is back this year, and Chancellor said it’s absence has made everyone playing more eager to get back on the court and get noticed by coaches.

“Going into next year, a lot of students feel that they haven’t really gotten the looks that they deserve this year,” Chancellor said. “They feel an extra sense of urgency to really get in the gym and to shine each game because they feel as if this year has really been stripped from them.”

[divider]Credit/no credit caused fear[/divider]

When PAUSD announced on March 25, 2020 that it would employ a “credit/no credit” grading system for the spring semester, many students, particularly those applying to college in the coming months, feared the decision would negatively impact their admissions decisions.

But Superintendent Don Austin said the decision to freeze student grade point averages was made to mitigate any damage remote learning might inflict.

“We worked with legislators, the governor’s office and the UC/CSU system officials,” Austin said. “Once we were assured that there would be no penalty, we made the move to credit no credit. Surrounding districts had explosions of Ds and Fs. Grades suffered throughout the nation, while our students earned credit and focused on learning to navigate an online curriculum.”

Austin said the district’s decision was made in the interest of giving students leeway to preserve academic performance during the uncertainty of the beginning of the pandemic. However, many then-juniors like Catherine Reller were relying on the spring semester to demonstrate an improvement in their grades and felt cheated when they learned colleges wouldn’t see them.

“I wanted to show an improvement curve in my grades from the fall semester,” Reller said. “A lot of the schools I had intended on applying to had high GPA requirements for admission, and I was going to use my second semester grades to my advantage. It was really disappointing to hear that I wouldn’t get that opportunity.”

Despite pushback the district received following the announcement of the decision, Austin said he is pleased with the final outcome and to have helped pioneer alternative educational routes during the pandemic.

“I am very happy with our decision in retrospect,” Austin said. “Many across California, Oregon, Washington and the rest of the country used us as a model and followed in our footsteps. I knew there would be opposition from people who thought we would be disadvantaged. I trusted the people I called and made a decision. It was one of a lot of decisions I had to make over the last year and a half and one of the decisions I feel best about looking back.”