When the COVID-19 pandemic struck last March, Michael James was working at Ikea in East Palo Alto and living comfortably in his apartment. He said he put away a large part of his income into a monthly savings account, but when California began its state-wide shutdown, Ikea put its employees on furlough, and that savings only lasted for two weeks.

Luckily for James, unemployment checks and the first stimulus package arrived soon after Ikea let him go, and he could leave his savings alone for the time being. But the checks were infrequent and barely covered James’ rent — so he was forced to find a food bank for his groceries.

The U.S. Agriculture Department says food insecurity is defined as lacking consistent access to enough food to maintain an active, healthy life. While COVID-19 has exacerbated food insecurity, it is not a new problem — cases have been rising annually even before the pandemic. In 2018, Feeding America found 1 in 10 people in the Bay Area were food insecure, and the continued gentrification of California contributes to worsening numbers by the day.

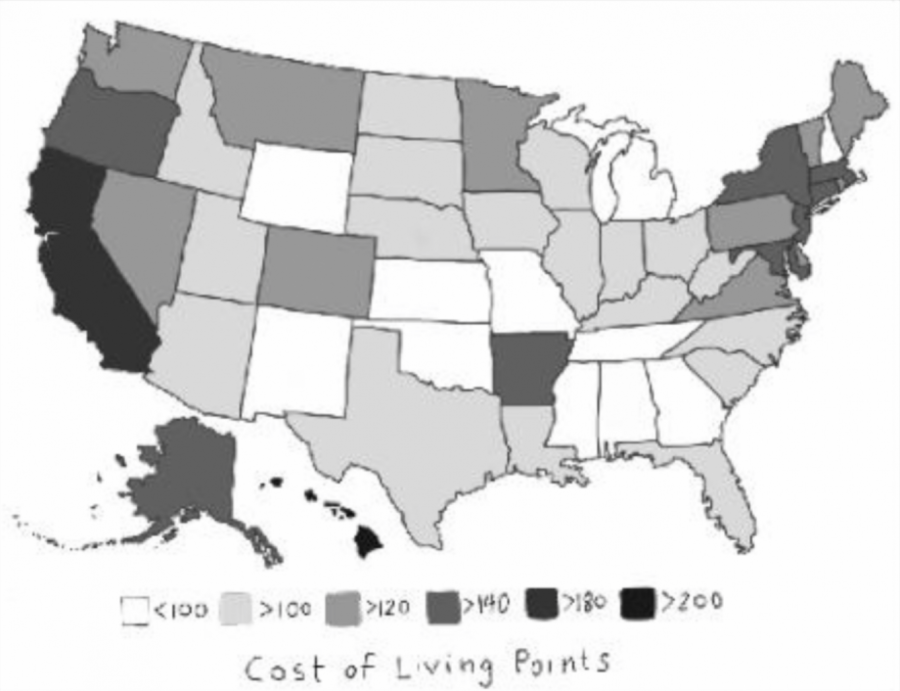

The USDA says food insecurity comes more from having an unstable salary and a fluctuating economy than a lack of available food. Frequently, a population of food insecure individuals live in a condensed area in the vicinity of an affluent city. The affluence of these cities raises the cost of living and prices necessities like food through demand and higher taxes.

The first stimulus package and wave of unemployment checks distributed in April 2020 was created with a national standard much lower than that of the Bay Area in mind; it barely made a dent in the rent, loans or short-term debts of Palo Alto families, according to James.

“It made a day or two better because I took it and used it to break off arrangements I had,” Tinka, a widowed mother and recently re-employed teacher, said. Tinka declined to give her last name. “If I had a bill that still had $300 left that would be paid in $50 segments I would go ahead and pay the whole thing until I ran out of money, because I still have so many arrangements.”

The federally-provided funds were meager, inconsistent and unreliable, according to James, and much of the East Palo Alto community viewed them as an occasional bonus instead of a salary to live on.

“I didn’t get it every month,” James said. “The stimulus package also helped a little, but you never knew if you were gonna get it, so it wasn’t a good source of income.”

And the pandemic as well the instability of the marketplace in the past few months have taken a serious toll on those already struggling before the pandemic.

Maria Otadoy, a special education teacher in the Ravenswood City School District, said she has been going to the Ecumenical Hunger Program — a service that provides food, clothing, furniture, supplies and financial assistance to those in need — since March 2020. She said she drops off the food she picks up there to help the family of one of her students who is severely disabled.

“In March they had a newborn son, and their other son is severely disabled, and because of COVID-19, the husband didn’t have work and was out all day doing small jobs,” Otadoy said. “They did not have money or food, and there was no way for them to be able to pick up the food, so I signed them up.”

But coping with food insecurity has also become a reality for some who are financially stable. Erica DiCarlo, a single mother of four, who is working toward a career as a nutritionist, said she and her family are finding it hard to make ends meet while she puts herself through college.

“I am three classes away from earning my degree which is great, but right now I am living paycheck to paycheck and some weeks I really struggle,” DiCarlo said. “Right now we just make it work, and I budget really strictly to make sure my kids are eating healthy. Under the roof of my house, we don’t overeat or waste food, and we always save our leftovers for the next day.”

A related issue to food insecurity is the part that it plays in poor nutrition. Healthy food is more expensive than fast-food, but good nutrition, especially for children, fosters healthier eating habits and prevents food-related diseases such as obesity, high blood pressure and diabetes.

Rodea Grant, a senior living in East Palo Alto, is retired and lives off welfare and unemployment checks. She said she has relied on EHP since it opened in 1978 to support her and her son, who has since grown up and moved out.

“I was a single mom, and I worked really hard, but my money always went to rent and supplies,” Grant said. “I would have a tight budget to go to Lucky’s for the healthy stuff, and if I had enough that week, I would try and go to Safeway. The rest, like the pasta and cans, I would get at EHP.”

When Grant’s son was growing up, she said fruits, vegetables and meat weren’t available at EHP and for many weeks, she wouldn’t be able to buy him enough food, especially since programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program wasn’t widespread or accessible at the time. Even now, single moms like DiCarlo struggle to get enough fresh food for their children, despite having access to those resources.

Since the pandemic, EHP serves everyone who asks for help and doesn’t require proof of income for its services. Director Lesia Preston said the organization has turned its parking lot into a drive-through food distribution center to keep staff and customers safe and accommodate the increase in families who require services.

“We focus on food and hygiene but also provide furniture, clothing, supplies, things like glasses and financial aid,” Preston said. “That includes doing things we would never normally do, like helping people with rent, prescriptions or a bill because of being out of work or losing hours at their job.”

While there are several food banks and shelters in Palo Alto and East Palo Alto, awareness of these resources is limited, Grant said. Most of the information about these aid programs is spread by word of mouth, and because of this, Grant said more publicity about these programs would be helpful.

“I think it would help a lot if people knew about the resources that were available, with an email blast to families in Palo Alto through the schools,” Grant said. “Just to say food is there with fresh vegetables, and also information flyers and pamphlets across both cities because even a lot of people in East Palo Alto don’t know about EHP.”

The lack of organization among these relief structures could be remedied to the benefit of many. According to Grant, while there is a lot of community involvement and neighbors are helping neighbors, an entire locality strapped for money and support cannot adequately help those who need it.

“The more help we can and the more we can provide, not for a forever situation, but until people are truly back on their feet is what we need to be a part of,” Tinka said. “We need to help, and I don’t think that we are mobilizing fast enough.”