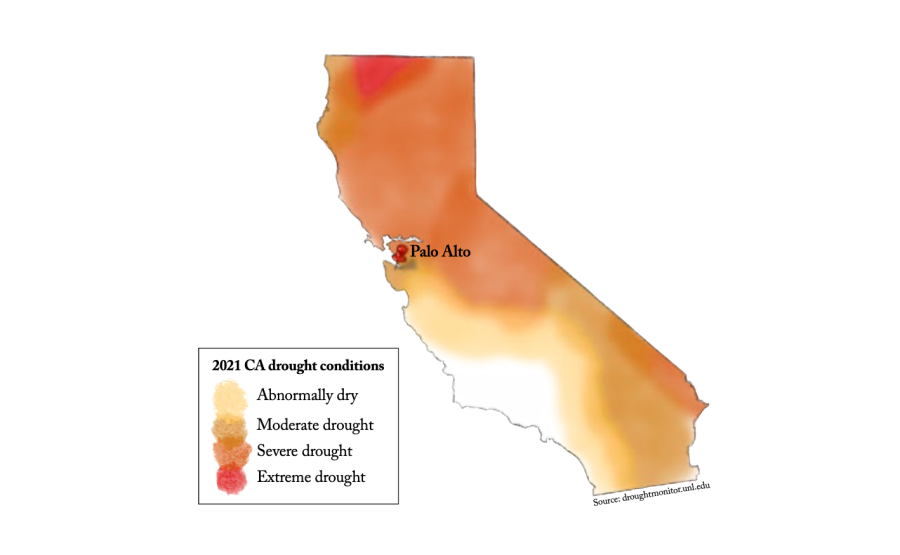

California will face another dry winter as La Niña 2021 approaches, prolonging the drought as rainfall and temperatures decrease.

La Niña is a routine weather event that amplifies the weather in the central and east-central equatorial Pacific due to cooling of ocean surface temperatures.

AP Environmental Science teacher Nicole Loomis said La Niña is a part of the El Niño Southern Oscillation cycle.

“El Niño and La Niña events occur every two to seven years on average,” Loomis said. “This is the duration of the ENSO cycle, and it varies.”

This year will be the second consecutive La Niña — also known as a “double-dip”— and means the Bay Area can expect changes in weather.

“Generally it is precipitation that is affected — in the eastern Pacific, we will see less precipitation during a La Niña year, so more drought,” Loomis said.

According to Loomis, the decreased rainfall in the Eastern Pacific will affect wildlife as well.

This has impacts on terrestrial ecosystems, and can increase risk of wildfires,” Loomis said. “In coastal waters, there is an increase in coastal upwelling, which brings nutrients up from the deep, so that is good for offshore ecosystems and fisheries.”

Loomis also said either El Niño or La Niña can happen every year.

“A La Niña year occurs when the tradewinds, which normally blow from east to west between the equator and 30 degrees north and south latitude, become more intense than usual,” Loomis said. “This increases low pressure systems over the western Pacific and high pressure systems over the eastern Pacific. Low pressure systems are associated with more rain, and high pressure systems are associated with more drought.”

El Niño, however, is the opposite of La Niña.

“An El Niño year occurs when the tradewinds, which normally blow from east to west between the equator and 30 degrees north and south latitude, slow down or even swap direction and blow from west to east,” Loomis said. “This reverses the normal pattern, causing increased rains in the eastern Pacific and increased droughts in the western Pacific.”

To determine whether a year will be a La Niña year or El Niño year, Loomis said weather forecasters analyze the Earth’s atmospheric and oceanic models.

“The forecast for this year has already been published based on the models,” Loomis said.

Loomis said outside factors such as global warming increase the frequency and intensity of the ENSO and its weather patterns.

“El Niño and La Niña events can vary in frequency and intensity — it is expected that the frequency of intense events will increase from about once every 20 years to about once every 10 years,” Loomis said.

Junior Ava Shi said her family is prepared for the predicted drought.

“My family already has methods we use to reduce the amount of water we waste, so we’ll probably continue that and in general just be more aware of our water consumption,” Shi said.

Junior AP Environmental Science student Kylie Tzeng also said she will be more cautious of her water consumption.

“I will take shorter showers and not leave the faucet on when washing dishes,” Tzeng said.

Loomis suggests Palo Altans prepare for drought conditions before they become irreversible.

Loomis said, “Conserve water, remove lawns and replace them with drought tolerant plants, install rain barrels and create defensible space around your house if you live near wild areas.”