[divider]Evolution of juvenile justice[/divider]

While the United States has a separate justice system for juveniles, that hasn’t always been the case. In fact, prior to the 20th century, youths were tried in the same criminal courts as adults.

The roots of the present-day juvenile justice system can be traced to the late 19th century when changing perspectives about mental health led to the growing belief that young people are less morally and cognitively developed than adults. This belief led to the establishment of the first juvenile court in Cook County, Ill. in 1899. Following Cook County’s model, juvenile justice systems that used restorative-based punishments like probation spread across the nation.

As the juvenile justice system evolved, harsh punishments for juveniles such as solitary confinement were replaced by enforced community service and therapy.

But during the late 1980s to 1990s, the United States saw an increase in violent crime, prompting the federal government to adopt a “get tough on crime” policy, focused on sentencing convicted criminals to longer prison sentences.

The “get tough” approach, headlined by then-President Bill Clinton’s 1994 Crime Bill, included harsher punishments for young people in an attempt to scare them straight.

This approach continued into the early 2000s, giving prosecutors more power in juvenile cases. It was not until February 2021 that the California Supreme Court barred state prosecutors from trying children under the age of 16 as adults.

History teacher Jack Bungarden said the United States’ history of harsh punishments of children during the late 20th century, especially children of color, is another example of the country’s history of racism.

“Kids were tried as adults pretty commonly,” Bungarden said. “Some crimes were seen as more egregious, and that they tended to be toward kids of color seems to be reasonably established.”

This racial bias persists today, supported by studies such as one from the University of South Carolina which found that Black youth were nine times more likely to be sentenced to an adult prison than white youth.

In an effort to undo this harm, juvenile centers, including ones in Santa Clara County, have reinstituted reform movements involving probation and restorative justice for adolescent offenders.

[divider]Santa Clara’s shift to restorative justice[/divider]

Chief Laura Garnette from William F. James Boys Ranch, a juvenile detention center in Morgan Hill, said her program follows two guidelines: the Missouri Model, which emphasizes addressing the root causes of juvenile delinquency rather than fixing surface-level behavior, and the Dr. Bruce Perry theory, which explains how trauma affects the brain and guides the staff how to ask more open-minded questions.

“It’s about really getting to know the kids because then you know how to intervene,” Garnette said. “I think it’s a much more holistic way to treat people in confinement.”

Instead of strict discipline, Garnette said she and her staff of probation officers at William F. James Boys Ranch focus primarily on making sure children in juvenile facilities feel safe.

“Families can visit every day where they can bring in food and have picnics,” Garnette said. “At Juvenile Hall, they play cards and talk, and the wrap teams and probation officers do really intensive work with the families.”

Garnette said she tries to reassure the youths in juvenile facilities that their families are there for them, regardless of what the adolescents are going through.

“(These) kids are out of control right now, but it isn’t the time to not be there for them,” Garnette said. “It’s the time to figure out how to be there for them in a different way.”

In a continued effort to reverse the damage of juvenile facilities on youths, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed an executive order to phase-out California’s state-run juvenile detention centers and place juveniles in county facilities instead, following in the footsteps of Connecticut and Washington.

Garnette said that while the legislation was a step in the right direction, it places an unnecessary amount of stress on county juvenile departments because of the lack of effective planning.

“It feels like too much too fast,” Garnette said. “If they had gotten the admissions office up and running, made some provisions for the highest risk youth and worked on regionalization, it would have been way better.”

Garnette said that due to the lack of planning on the part of the state, county juvenile offenders have had to consider how to deal with the relocation of high risk juvenile offenders, especially for detention centers designed for low risk youth.

“Our ranch is in too much of a residential area to have high risk youth,” Garnette said. “There’s no locked doors. There’s just a fence.”

The county deadline to come up with a solution to reduce the danger posed by having high-risk youth in their low-security facility is Jan. 1, 2022.

Garnette also said the ranch does not want to install tighter security measures because it would detract from the open-minded environment they have worked hard to create.

“We’ve learned a lot in the past few years about trauma-informed care and how to make our facilities (have) less triggers,” Garnette said. “Trauma-informed training has made the biggest difference as far as reducing fights and reducing staff having to restrain kids.”

[divider]From juvie to Paly[/divider]

At Paly, special education teacher Chris Geren helps students who have transitioned back to school from a juvenile justice facility meet the requirements of their probation.

He said his primary goal is to help these students understand how the path they are headed down will impact their future.

“When people are 16 and 17 years old, they don’t realize the impact (their actions) are going to have on the rest of their lives,” Geren said. “It’s important for me to drive it home to the students that they need to get their act together: get their hours done, go to class and be responsible.”

To meet the requirements of their probation, including completing the mandatory number of community service hours before they turn 18, Geren said he works directly with Santa Clara County and the student’s probation officer.

Because the school does not have a formal transition program from Santa Clara County Juvenile Detention Centers to Paly, the responsibility of helping students meet the requirements of their probation falls on staff like Geren.

But Assistant Principal Jerry Berkson, who has been in charge of student discipline for 16 years, said there is no need for a district program because of how few students they get from juvenile facilities.

“I could probably count on less than 10 fingers how many kids (from Paly) that I’m aware of that have ever been to juvie,” Berkson said.

Berkson said he thinks the low rate of kids going from Paly to juvenile hall is largely due to the system’s shift to therapy and reconciliation-based punishment, as well as Paly’s academically motivated environment.

Berkson also said the school is not notified when someone from a juvenile institution enrolls at Paly. This lack of information means the school is not necessarily aware of who has or has not been to juvenile detention.

“I’m not sure we get an official notification from the courts,” Berkson said. “The only reason I know that they’ve been to juvenile hall is because people feel comfortable talking to me about it.”

Although restorative justice can be beneficial, Berkson said there is a time and place for more punitive measures in cases of continued offenses when other approaches have failed.

“I just don’t know how many restorative things you can do,” Berkson said. “At some point, you need to hope that they can be scared straight.”

The Campanile reached out to multiple students who have transitioned from the juvenile justice system to Paly, but none of them wanted to be interviewed for this story.

[divider]New mentorship program approach[/divider]

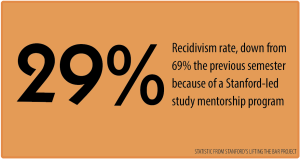

In a joint study by Stanford University, UC Berkeley and the University of Michigan, researchers examined how a mentor in the lives of children going through the juvenile justice system can help mitigate the stigma they face when returning to school.

“The goal of the intervention is to sideline all of that bias and help the kids form connections,” Walton said. “And then let (the adult) do the hard work to address the challenges that the kid faces and help that kid make progress.”

Gregory Walton, an associate professor at the Stanford Department of Psychology who contributed to the study, said punitive measures can harden juveniles into criminals later in life.

“You want to make people criminals, you treat them like criminals,” Walton said. “The more that we can treat people as having the potential to be ideal, and then help them become that ideal, the better.”

Walton said one unique part about this mentorship is students choose which adult at their school they want their mentor to be through a letter.

Walton said, “Our approach is elevating kids’ voices and kids’ choices in who they would like to be a support for them among the people that they are going to be interacting with.”

According to Walton, having a chosen trusted adult at school who believes in them can be critical for youths with an unstable home environments.

Walton said, “If there’s instability at home, having a secure base at school and a relationship with an adult at school that’s trusting and supportive can make all the difference.”