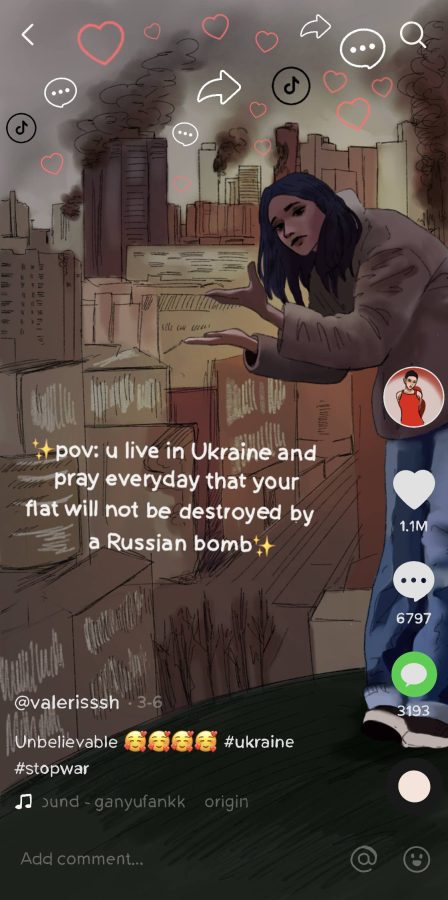

Ukrainian TikToker Valeria Shashenok walks through her neighborhood with her camera, capturing collapsed buildings, smashed windows, pieces of debris strewn about and a look of dejection plastered on her face for the world to see.

Despite these devastating circumstances, Shashenok’s dark humor peeks through with a caption on one of her posts that reads, “Putin I wait (for) u in Chernihiv,” followed by four smiley-heart emojis.

Less than two months ago, Shashenok was just a 20-year-old Ukrainian photographer, posting the behind-the-scenes of her recent photography shoots for her friends to see.

To many of her followers, like senior Lily Lochhead, the combination of Shashenok’s relatability and humor make her videos both familiar and eye-opening.

Lochhead, whose grandparents lived in both Ukraine and Russia, said Shashenok’s videos are valuable because they are a primary, candid view of the war.

“With these videos, we’re able to not just rely on news sources and the government to tell us what’s going on,” Lochhead said. “We can actually see (the war) with our own eyes, which gives us the ability to interpret the war for ourselves instead of blindly following news sources that sometimes have false information.”

Shashenok said in an interview with CNN reporter Pamela Brown that many of her friends fled Ukraine at the start of the war, but Shashenok took shelter with her mother, father and dog in an underground bunker in northern Ukraine for several weeks. On March 14, Shashenok posted on her TikTok that she had safely evacuated to Poland.

In the same interview with CNN, Shashenok also said it is her duty to debunk fake news from Russia by providing an unfiltered lens into reality and hold Putin responsible for the havoc he has wreaked on her country. “I feel it’s like my mission to show people how it looks in real life. That it’s real life, and I’m here,” Shashenok told CNN.

AP US History teacher John Bungarden said TikToks like Shashenok’s are critical to the world’s view of the war because they show Ukrainians’ strength against Russia.

“The Russians expected, from all that’s been reported, for Ukrainians to collapse quickly, but they haven’t,” Bungarden said. “It’s certainly because of Ukrainians’ courage. (It shows) heroic leadership, something we can appreciate.”

Despite the benefit social media provides as an uncensored insight into the war, fake news videos, including government-paid Kremlin propaganda, have been circulating on TikTok.

To add to this problem, Russia recently passed a “fake news” law, making it a crime to publish any news about Russia’s military hostilities that differ from accounts from its Military of Defense. This law would mean only government-approved videos could be published on social media platforms such as TikTok.

To combat this issue, TikTok suspended live streaming and video uploads from Russia, following Meta, Twitter and YouTube’s lead.

“Our highest priority is the safety of our employees and our users, and in light of Russia’s new ‘fake news’ law, we have no choice but to suspend live streaming and new content to our video service in Russia while we review the safety implications of this law,” TikTok said in a statement.

Though TikTok’s ban has helped reduce uploaded misinformation from the Russian government, it is still prevalent on the app. Bungarden said one of his main problems with social media platforms is that they let dishonest and dangerous videos live on forever, not only on TikTok, but all social media platforms.

“(Social media platforms are) there to make money,” Bungarden said. “The people who are in the position to at least somewhat mitigate its effect either can’t do it or won’t do it because to do it is to interrupt their business model. So the lies get to live on.”

Though social media platforms may not mitigate misinformation, Bungarden said social media users can prevent their susceptibility to fake news by fact checking everything they read.

“When you see something that confirms what you believe or when you see something that confirms the other guys are evil, be skeptical and see its confirmation,” Bungarden said.

Besides spreading fake news, Lochhead said dishonest and violent videos can be difficult for many Ukrainians — including herself — to see. Lochhead said she understands humor can be a valuable coping mechanism, but people whose lives aren’t being directly affected by the war should be conscientious about how their humorous videos come across to ensure they aren’t being offensive and hurtful.

“We should be careful about what we post because it can be really traumatizing for a lot of people,” Lochhead said. “People’s stories are so much more complex than what we see on the internet. A lot of times they’re sacrificing much more than we realize.”

While the spread of misinformation is an unavoidable risk, Lochhead said the benefit of seeing what’s actually going on in Ukraine outweighs this risk of fake news.

“At the cost of misinformation, (social media) is worth it because we learn so much more about what’s really going on,” Lochhead said. “We just have to be able to filter (misinformation) out.”