Should a student’s number of APs be limited? YES

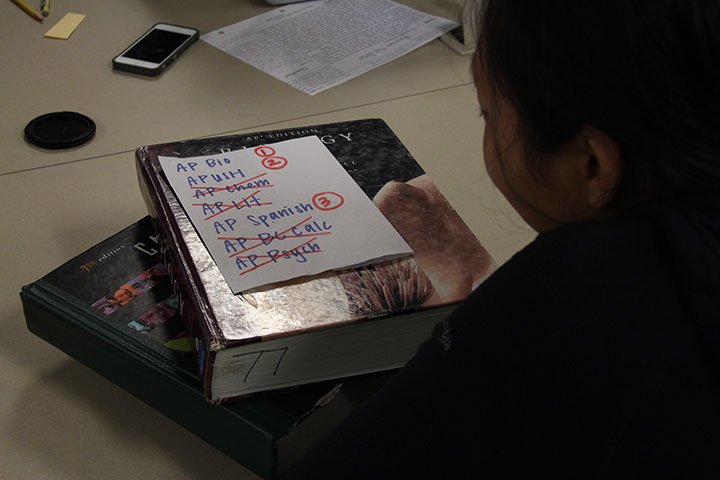

The administration’s new time management worksheet and its suggestion to limit students to only take two Advanced Placement courses per year has raised the question of whether APs should be forcibly capped

Some Teacher Advisors have tried to limit the amount of APs their students may take.

Palo Alto students live in an extremely competitive environment. And with the prize of college admission to top-tier universities becoming ever more elusive, this competition reaches another level. Say Person A decides to take three Advanced Placement (AP) classes, a rigorous but manageable course load. When Person B finds out about this, in order to appear more competitive for admissions, they decide to take four APs. Person C ramps this up to five AP classes to edge out his or her competitors. By the time we arrive at Person D, there is a serious problem.

So who needs to reign in the competition? Administration. Starting this year, Palo Alto High School requires students to fill out a time management log prior to signing up for APs. This system aims to assist students in reflecting on how they spend their time and the practicality of taking an AP. Along with the time management form, Paly’s administration has introduced a suggestion of two AP classes per year. This guideline, while admirable, lacks enforcement.

According to the College Board, which oversees APs, the “Advanced Placement program enables students to pursue college-level studies — with the opportunity to earn college credit, advanced placement or both — while still in high school.”

For those that feel that limiting AP classes hurts college applications, Paly can clarify this policy to admission officers. This would place more emphasis on extracurriculars and other ways students demonstrate college readiness and rigor outside the classroom. To show dedication to a topic, students could volunteer or pursue an internship, giving students hands-on experience not always available in an academic setting.

A key aspect of AP courses is that they prepare students for a comprehensive examination in May. These tests are scored on a five point scale and evaluate a student’s knowledge of the subject in different formats. The looming May test date restricts teachers’ ability to teach freely. Instead they must “teach to the test” and prepare students to be knowledgeable in the areas deemed necessary by the College Board, rather than covering the material they feel is most applicable.

For that reason, several top public schools have phased out APs, opting instead for their own version of advanced courses that give teachers more freedom in designing the class. Most prominent in this movement is Scarsdale High School in Scarsdale, NY, which is considered “a precedent for high-achieving public schools,” according to the New York Times. Scarsdale’s system, Advanced Topics, was developed by professors at top universities to cover applicable material without the confines of a standardized test. For those that fear limits on AP testing would jeopardize competitiveness for college admissions, 49 percent of Scarsdale’s class of 2008, after Scarsdale began limiting APs in 2005, attended a group of top 80 schools, as defined in the New York Time’s article by Barron’s Profiles of American Colleges. This can be compared to 47 percent of students in the class of 2007.

If a student meets a certain score outlined by a university, he or she may qualify to test out of introductory level courses or receive college credit. But this practice is increasingly less popular for college administrations because colleges prefer students to take their own introductory courses to ensure an adequate foundation. According to a 2011 New York Time’s article, schools like the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of Texas no longer accept AP credit for Biology or require a score of a five for credit.

Above the appeal of college credit or genuine interest, students opt for AP classes not only to challenge themselves, but also to impress colleges with their advanced schedules. Challenge is by no means a negative attribute. If a student has a strong interest in a certain subject, he or she should take an AP class in that area. But that does not imply that students should fill their entire schedule with AP courses; this expectation creates unnecessary stress and competition.

Administration should implement a limit of only three AP courses per year, forcing students to select classes that they are genuinely interested in pursuing, instead of picking classes for the two letters that appear before it on a transcript.

There is more to life than what classes you take in high school. Demonstrated rigor and interest should be appreciated, but creating an atmosphere of competition, pressure and stress should not.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Palo Alto High School's newspaper