With presidential candidates like Donald Trump seizing control of the nation’s politics, educating the masses is more important than ever. In the United States, an alleged paragon of democracy, voter turnout was at an embarrassing 57.5 percent in the 2012 election (a number which has been on the decline since the 2004 election) according to the Bipartisan Policy Center.

Teaching students about electoral politics begins a self-sustaining cycle of political efficacy.

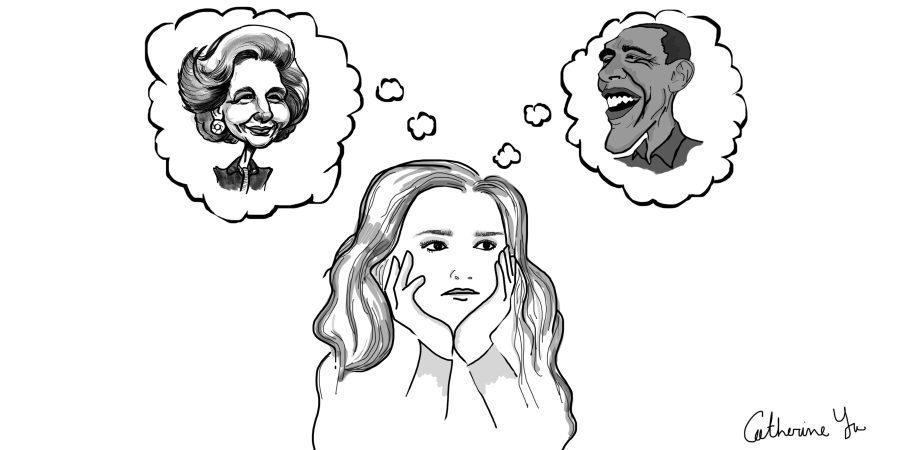

The capacity of the youth vote to swing the election remains as potent as ever. However, widespread political indifference of American students squanders this potential, while also inspiring a culture of political lethargy in incoming generations of voters.

California high schools are required to teach courses such as World History and United States History in an effort to help high schoolers understand their roots and the chain of events that culminates in the present. The ever-tiring mantra, “Those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it,” springs forth readily from every history teacher’s mouth.

Meanwhile, Donald Trump, the lovechild of Adolf Hitler, Joseph McCarthy and a repeatedly concussed toddler, inches closer to the presidency as he employs tactics of fear-mongering and divisive campaigning. In order to apply history effectively to the present, students need to have a reasonable grasp on the politics of the present.

An unfortunate consequence of the exclusionary nature of American politics is that politicians almost universally attempt to make the issues they deal with seem unnecessarily complex. This makes delving into the world of politics seem daunting, discouraging many young voters from making an educated decision.

Educating students on basic electoral issues, such as ObamaCare, immigration, foreign policy and the prison industrial complex allows students to understand the stream of media that is crammed down the American public’s throat. Campaigns will do more than half of the work — American students are already being bombarded with the messages, they just lack the tools to effectively understand them.

Teaching students about electoral politics begins a self-sustaining cycle of political efficacy. When students understand the issues, they are able to take a side and begin a political dialogue.

At Paly, there already exists a lively dialogue among students who take the time to learn about relevant national issues. However, its scope is insufficient and reflects the 57.5 percent voting rate — and Paly is evidently one of the more politically active schools in the nation.

Once a dialogue is established, students begin to educate one another through argumentation and are more inclined to pay attention to the constant stream of information that comes from all directions during election season.

Evidence shows that voter behavior during the first few election cycles of an individual’s adulthood is a strong indicator of lifelong political behavior. Getting students invested in political issues and facilitating the development of their opinions and stances primes them to vote in their first election as they begin to enjoy the privilege of finally having their voices heard. Whether their votes goes to the winning or losing party, they will continue to come back to the polls.

Given that the 4-year presidential election cycle aligns perfectly with a 4 year high school, the mechanism to educate high school students should be based on the presidential race.

History and social science classes during the election year should be adjusted to include a curriculum based on the election. Every history class can weave current election politics into their respective curricula — economics can cover fiscal policy, world history can examine the evolution of major electoral issues and foreign policy simply needs to examine the partisan nature of U.S. foreign policy.

American teens are apathetic about too many things — politics should not be one of them.