There is a common misconception that reading stories aloud or being read to are skills that are mainly relevant to children. Oral storytelling plays an important role in students’ learning in their elementary education, but seems to have little to no place in the classroom as students age.

In most high school classrooms, if a teacher wants their students to read a text, they will often opt to link it online and instruct the students to read silently to themselves.

Whether it be the interference of technology in the classroom or the notion that young adults have outgrown the need for oral reading, reading aloud has become somethin of a lost art.

However, in English electives teacher Lucy Filppu’s Creative Writing course, things are done differently.

Filppu reads the articles and short stories that she hands out to her students out loud as much as possible, and the entire class respectfully remains silent, laptop screens closed, listening to the sound of her voice or the voice of another student.

“The number one reason I [read aloud to my students] is because I think that in order to write creatively and be able to create dialogue and poetry and rhythm, you have to be able to have an ear.”

Lucy Filppu

Filppu is adamant that her students detach themselves from their electronics when it’s time to listen to someone read, because she wants them to get the most out of the experience as audience members.

“One of my concerns is that in the age of screens and institutionalized schooling, students are losing their ears,” Filppu said. “Part of writing and enjoying the process of reading is being able to hear the voice inside your head. Whether it be the voice of the narrator or the voice of the character, the cadence in the way someone speaks, or the tone, it’s important for the audience to take it all in.”

Christina O’Konski, a theatre student and senior in Filppu’s Creative Writing class, echoes Filppu’s argument, touching upon some of the benefits of reading aloud and how it changes the manner in which students engage with the text.

“In this age, everything is so fast,” O’Konski said, referring to the accessibility that the internet provides and how students can switch between assignments and websites in the blink of an eye. “When you read in your head, particularly off of a computer screen, you tend to unconsciously skim the material that you are reading, and that can be really dangerous. You tend to miss much more and often [miss] the entire main idea. I think that reading aloud forces you to really take in what you’re reading, especially if you go beyond the bare minimum of just saying the words out loud.”

According to O’Konski, the tone of the reader can have a positive impact on the amount of material absorbed.

“If you don’t just read in a monotone, but you instead try and use inflections, or mimic their emotion, it absolutely gets you more engaged with the writing,” O’Konski said. “Making the effort to sound like you understand the material can be beneficial.”

The effort that the reader puts in can make the experience more enjoyable for not only themself, but the listener as well, according to Filppu.

“I absolutely love listening to my students read what they’ve created,” Filppu said. “I find the intimacy of the human voice far more compelling than what I read on paper or on a screen when they turn in their work for credit. I want to see them present their writing to me with their voice.”

O’Konski has become comfortable reading lines through the theatre program.

When she reads aloud to an audience, she pushes herself to encapsulate the characters she is playing.

“Sometimes, when I’m reading lines, particularly Shakespeare, I’m advised to rewrite the words in my own way in order to understand what I’m saying,” O’Konski said. “Then I can put the words back and I have the meaning underneath. Now I understand the intonations and how to say [the lines] properly, and then I can convey the right feeling from the word choice.”

Learning how to impersonate the characters in a reading is an important skill, and this is part of the reason that Filppu made it a requirement in her Creative Writing class to read one of your own works in front of the class.

“I want my students to learn how to work as a professional and own their voices,” Filppu said. “I have some students that naturally love to read their writing, but I know it doesn’t come as easily for everyone, I am always ready to work with a shy student and help them accomplish that.”

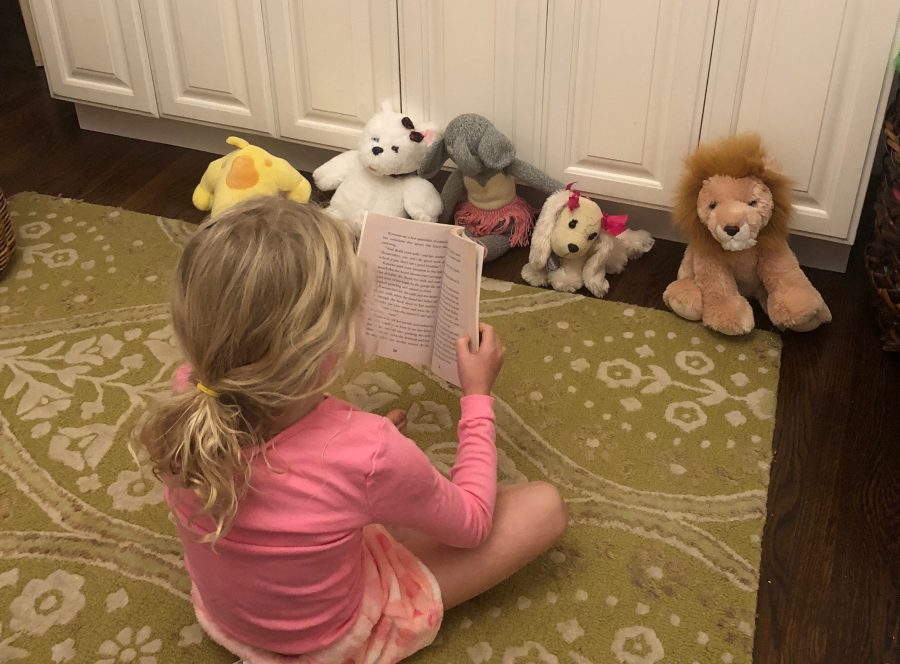

O’Konski was introduced to oral storytelling at a young age.

“There’s this huge ritual of storytelling, but it’s mostly just to kids,” O’Konski said. “I would get read to as a kid, when I was getting ready for bed, and there’s just something entirely different about hearing a story read aloud and focusing on the sound of someone else’s voice. I don’t know why these bedtime stories are seen as something that’s just for kids.”

Professor Barry Zuckerman of the Boston University School of Medicine conducted a study on the benefits of reading to young children.

Zuckerman found that in addition to aiding language development, the practice also establishes a parental connection.

“Reading aloud is a period of shared attention and emotion between parent and child. Children ultimately learn to love books because they are sharing [their books] with someone they love.”

Professor Barry Zuckerman

According to Filppu, these benefits can extend to a demographic that includes children and adults alike.

“Many people are aware of the positive effects of reading to their children,” Filppu said. “But why let it stop? Reading out loud must be a part of every student’s life, and must be a part of every single person who wishes to grow as a writer’s life.”