The names of sources who spoke on the condition of anonymity have been changed.

[divider]Introduction[/divider]

Everybody’s doing it,” embattled college coach William Rick Singer said in a 2013 YouTube video, “it” referring to high school students doing all they can to boost their chances at college admissions. What appeared to be an innocent pep talk video was recently unveiled as a small aspect of the largest college admissions scandal ever prosecuted in the U.S., ensnaring celebrities and global CEOs and prompting Americans to reflect on the fairness of college admissions.

More broadly, the scandal highlights an issue that has become ubiquitous: a sinister culture of dishonesty. Silicon Valley is no stranger to lying, from the defunct Theranos claiming to have revolutionized blood testing to Apple purposely slowing down older iPhones via software updates and telling consumers the updates prolonged battery life.

Perhaps even more pernicious and relevant to people’s daily lives than corporate wrongdoing is the lies students and parents spread. Rather than becoming the exception, dishonesty appears to have become the norm in the everyday lives of the younger generation – at the expense of moral integrity, interpersonal trust and mental health. As Generation Z is taught to win at all costs, and morals are questioned, a powder keg is set up to explode as the current generation of professionals is phased out and a new breed of people with different values and worldviews replace them.

[divider]Duck Syndrome[/divider]

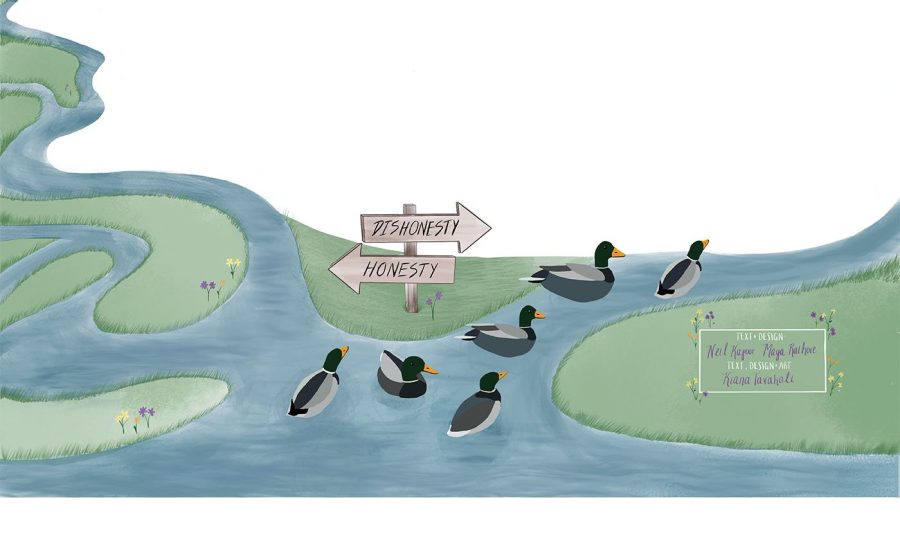

Stanford University freshman Alex, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, has only been at Stanford for the past seven months. But like many of his classmates at Stanford, Alex said he is well-aware that the prestige and perfection associated with his elite university often mask the pressure students experience — a phenomenon known as the “Stanford duck syndrome.”

“Duck syndrome,” a term coined at Stanford University around five years ago, compares the happy façade college students often project to the way a duck appears to glide calmly and gracefully while actually frantically paddling underneath the water’s surface to stay afloat.

“The duck syndrome is totally present at Stanford,” Alex said. “If someone scores a B and they’ve never scored a B in their life, they’re just going to be like, ‘We’re OK with it,’ and show everyone they’re happy, because it’s the status quo here.”

Despite the popularity of the term, Alex said he initially did not realize how prevalent the duck syndrome was until late fall quarter.

“(The duck syndrome is) very subtle,” Alex said. “It takes you some amount of time to realize that not everything is OK … But it’s very prevalent once you get to know about it.”

According to Alex, this systematic hiding of true emotions leads to the hiding of personal struggles at competitive institutions — be it at Stanford, Paly or elsewhere — at the expense of sleep and mental health.

“You still have to show you’re happy, and (for) a bunch of my friends, academically, this puts a huge pressure on us because … we’re struggling,” Alex said.

According to Paly junior Brian, who also spoke on the condition of anonymity, the duck syndrome has managed to infect younger audiences aswell, and has become a typical part of academic life for many Paly students too.

“I think that the duck syndrome is present in everyone, but it’s kind of localized. So if you look at some random person you hardly know at Paly and see how they’re doing, you’re probably like, ‘Yeah, they’re doing fine and are totally chill,’ but (if) you talk to any one of your friends, and they’re all totally freaking the f— out.”

Paly junior Brian

[divider]Generational Differences[/divider]

As baby boomers and Generation X start to leave the workforce, and Millennials start to replace their higher ranked white-collar and blue-collar jobs, Generation Z is expected to fill the holes in society. Honest and dishonest students progress through high school and college and enter important professional roles, such as doctors, lawyers, and politicians. Unlike previous generations, as a generation that was raised with a specific emphasis to win at all costs matures into adults, the potential for societal consequences is real. James Doty, a Clinical Professor of neurosurgery at Stanford University, said a generation that was taught to cheat and lie to survive as children will act the same as professionals.

“Somehow those parents believe it was OK for them to (win at all costs) in high school or college, but when they become a doctor or lawyer or professional, they will be a good human being. No — they’re going to demonstrate the same type of ruthless behavior and cheat, steal, do whatever’s necessary to be number one or to win.”

Stanford Professor of Neurosurgery James Doty

In addition to a set of degraded morals, another generational difference with potential consequences is Generation Z’s reliance on technology – specifically social media, a form of communication widely used by students and society alike. According to Jessica Clark, a Paly Counseling and Support Services for Youth head therapist, social media is part of the dishonesty that people experience today.

“We’re in a phase of our society (where social media) is a symptom, but also represents that duck syndrome,” Clark said. “You put your best face out to the world and hide your struggles underneath.”

As technology and daily life intertwine tighter, a constant stream of carefully curated and misleading highlights can have a detrimental effect on the mental health of users, and also reflects the mental health of the one who portrays their life perfectly online.

“The sad thing about individuals who have to be perfect on Instagram in terms of their looks or present this extraordinary lifestyle is that they are also suffering from a need for acceptance and love,” Doty said. “… it’s their peers (encouraging online dishonesty), it’s marketing, marketers using unreasonable perceptions of beauty… they’ll do anything, even be dishonest, to appear that way.”

A 2017 report from the Royal Society for Public Health in the UK found that Instagram is the most detrimental social media app to the mental health of people aged 14 to 24, followed by Snapchat. The report found that while Instagram can be a positive outlet for self-expression, the app can also negatively affects body image, sleep patterns and encourages the phenomenon known as “Fear of Missing Out.”

“You’re not posting pictures of you waking up out of bed with your hair all messed,” Clark said. “You’re posting the highlights of your life. So as you’re comparing someone else’s posts to your life, it looks like everyone else has this wonderful, pretty life, and it can be a false sense of what other people’s life really is.”

[divider]Parenting[/divider]

Paly senior Andrea, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said when she told her mother she had been deferred at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, her mother had an explosive reaction.

“She freaked out because she thought that I wasn’t going to get in anywhere,” Andrea said. “I told her, ‘It’s fine, I already got into another school,’ but she didn’t like the school that I got into — Arizona State University. She thought that despite the rankings and whatnot, ASU was a school everyone got into, and it wasn’t going to be good enough.”

Andrea’s mother’s reaction proved consequential.

“Because of this reaction, when I got deferred from Case Western, I didn’t tell her because I was scared of her reaction,” Andrea said. “For months, I said that I hadn’t heard back from many schools. It wasn’t until very later on did I tell her I didn’t get in.”

Senior Andrea

Andrea said her parents’ view about academics caused her to be dishonest with them throughout high school. “My parents are brutally honest when it comes to grades and schools,” Andrea said. “They aren’t afraid to say that a B is bad or that this school isn’t good enough … If I do poorly on a test, I’d rather not tell them. I would usually just say that I didn’t get it back yet … because that way they can’t critique it. They don’t see the trends that happen and just focus on the individual.”

According to Brian, parents do not understand the pressure Generation Z, those born between the mid-1990s to the early 2000s, faces.

“Every parent will say that they know it’s more intense for our generation, but I don’t think they really understand,” Brian said. “Like it’s hard, and sometimes it’s dirty — morally ambiguous.”

In fact, Brian said parents may have misconceptions about which students are inclined to cheat in school.

“Parents think, ‘It’s probably some degenerate who’s a drug dealer and whatever,’ or ‘Some overachieving nerd who wants to get into Stanford.’ Nah, dude, everyone does it.”

Junior Brian

In addition, parents sometimes play an active role in perpetuating their child’s dishonesty by lying themselves – for example, when a parent calls their student in sick or excuses them from class when they aren’t actually ill. According to David, this is common among him and his friends.

“Yeah, I cut class a decent amount,” David said. “My parents always knew when I cut class and always approved — they emailed the attendance office and had me excused as needed.”

David said he was willing to be dishonest with the attendance office due to the demands of pressing extracurriculars and difficult classes.

“Neither I nor my parents had any qualms about lying to the attendance office,” David said.

However, according to Doty, when children learn to sacrifice honesty in order to further themselves, it can send the message that achieving what one wants is more important than anything else.

“Unfortunately, there are some parents or authority figures which children will look up to and they give the children the impression that they should try to win at all costs,” Doty said. “It is not related to values, it is not related to fairness, it’s not related to justice, it’s simply you must win. And that means someone else must lose. And when a child is presented with that type of an attitude, it’s not about learning for learning for learning’s sake, it’s not about being a role model for others, it is about winning, and that winning can be translated into straight As, that can winning can be translated into getting into an Ivy League school, or a very prestigious school.”

For example, Paly junior student Bella, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said she asks her parents to call her in sick for various reasons.

“Usually (I ask my parents to call in) for mental health reasons, which I feel is justified because it is part of my health. If I feel unprepared for a class or test, I skip periods to study and prepare and then go to school late. I don’t feel guilty for lying to the attendance office; I feel embarrassed that they hear from my family so much.”

Junior Bella

According to Doty, if a child is pressured by parents to achieve it can result in depression or suicide.

“If your only value is to those who look to you for love, and they define you those criteria, well then you do behaviors to attain what you believe will bring you love,” Doty said. “And sadly, that will often times involve cheating or doing other behaviors to get ahead.”

[divider]Academic Dishonesty[/divider]

When people think of academic dishonesty, they often think of students lazily asking their classmates if they can copy their homework, or a student furiously copying down their classmates’ answer on a test, frantically alternating between glancing at the paper and the teacher.

However, academic dishonesty is as broad as plagiarizing an essay, hoarding old exams or narrowing down possible College Board Free Response Questions that are guaranteed to be on the unit exams in Paly AP classes.

Brian said he and many others take advantage of the various methods of cheating out of what he said is a sheer necessity to keep his grades up, especially if it’s squeezed in between letter grades.

“Cheating is very common,” Brian said. “There’s only two to three people I know who refuse to cheat … When it’s such high stakes … you do what you have to.”Brian describes a culture at Paly that he said almost forces students to compromise their moral integrity simply because so many other students are doing it.

“To not cheat is a conscious effort to put yourself at a disadvantage.”

Junior Brian

And, according to Brian, there is no shortage of ways to cheat with little chance of getting caught.

“I’ve heard of some instances where entire tests were copied down on scratch paper and distributed,” Brian said. “I managed to narrow down the possible FRQ questions (Free Response Questions) down to five to six questions I got from College Board because I knew (my teacher) got them from there. If there’s a study guide someone made, some people will highlight which parts people should study. People always share essays, (and) as far as I can tell, as long as you’re not a complete idiot, you can manage to fool turnitin.com.”

Brian compared Paly’s academic environment to the Kobayashi Maru, a training exercise in Star Trek designed to train cadets for a scenario where there is no way to win, forcing the cadet to cheat by hacking the system.

“Captain Kirk cheated by hacking the computer, and when authorities interrogated him, he said this: ‘Cheating is the solution,’” Brian said. “‘If the goal is to win, and there is no way through orthodox methods, the only way to win is to cheat. So the test was designed to see how well I could cheat.’ Well, that’s how I imagine school. Everyone cheats, and if I don’t cheat, then I risk losing … School is testing my ability to cheat.”

According to Brian, part of the problem is student herd mentality: since so many other people cheat, people feel the need to cheat to keep up with their peers’ artificially inflated grades.

Paly junior Emma, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said students are even dishonest with their friends about their test scores because of a fear of seeming inadequate in comparison to their peers.

“I lied (to my friends) about my SAT score. I feel like (the issue is) more like me comparing myself to other students, and knowing that the kids at this school are really smart.”

Junior Emma

Another high-achieving student, Ava, who also spoke on the condition of anonymity said unlike Emma, her pressure to maintain high grades comes mostly from her parents, citing their immigrant status as a unique factor in her upbringing and perspective on academics.

“(Having) parents that are immigrants, I feel like it’s a common theme with immigrant parents that they want their kids to succeed, even if it means through ways that aren’t really the best for the kid,” Ava said. “Since elementary school, my parents have been talking about elite colleges like Stanford and how I have to get super great grades, and it’s just manifested.”

However, Ava said even if all parental pressure was eliminated, she would still feel the same pressure to succeed and potential lifelong inadequacy because of the values ingrained in her by the community.

“There’s a feeling of … inadequacy,” Ava said. “No matter where you are, being a child and growing you are cultivated and in a way you are groomed by your community. Even now, I work harder because I’m scared of my parents’ reaction, but at this point, it’s also for myself.”