[divider]Background[/divider]

Teenagers aged 13 to 18 tend to take many things for granted, and sometimes do not realize what rights they do and do not have. This largely includes medical rights, which impact critical decisions. Adolescents may face many crucial decisions about sexual health, such as sexually transmitted disease (STD) treatments, abortions, and mental health.

Such decisions have the potential to produce long-term, sometimes irreversible consequences. Yet, many teenagers fail to realize the consequences of remaining oblivious to their own rights. Teenagers are stuck in somewhat of a ‘between’ age — old enough to comprehend what is going on, yet too young to take full control of their lives.

Effective and honest communication between patients and doctors is the key to making informed and beneficial decisions regarding one’s health, and the system of consent that health care providers adopt — whether it be keeping certain sensitive aspects of adolescent lives private or limiting the involvement of parents in medical decisions plays a large role in ensuring safety for adolescents.

[divider]How it is different: Teens versus adults[/divider]

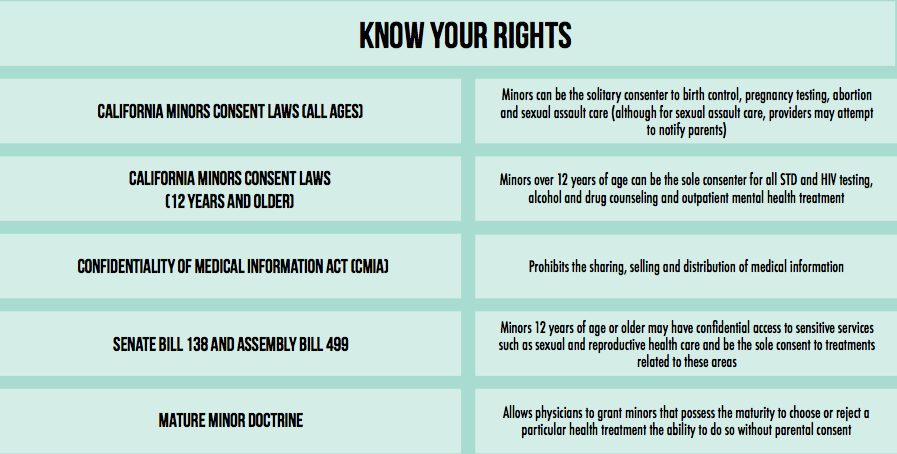

Although children clearly should not have identical rights and autonomy as adults regarding medical decisions, what about adolescents? For example, Senate Bill (SB) 138 — California’s Confidential Health Information Act — guarantees reproductive health care confidentiality and allows adolescents to receive care under a separate insurance plan from their parents. Aside from SB 138 and a few consent laws, adolescents have limitations very similar to those of three year olds.

Inequalities in the system stem from a set age of adulthood or majority in which one is considered independent, which in California is 18. Once patients turn 18, medical records are turned over to the new adult.

For teenagers and all persons under 18, medical records are generally not private. Although not entirely public, these records are available to parents, guardians and school administration. These records include all health information pertaining to the teenager, with the exception of sensitive reproductive health information. This is the law because the student may not feel entirely comfortable sharing sensitive information such as the act of STD-screening and sexual activity the student may not feel comfortable sharing with the entire school administration.

If adults share their medical insurance policies with their spouses, they may simply submit a privacy form to remove that person’s oversight and infringement on their privacy. Teenagers have no such right to a privacy form as they are underage, and thus cannot escape being pressured into receiving treatments that their parents view as preferable even if such treatments go against their own will.

“For adults, there isn’t a certain threshold [for breaking confidentiality] — when you’re over 18 and no longer have a legal guardian, there’s no one the doctor will tell if you’re harming yourself,” senior Luma Hamade said. “I also think that adults currently have the right to veto their children’s health care in a lot of situations.”

While privacy concerns are considered in adolescent reproductive health services, it can be argued that adolescent confidentiality should be extended to other aspects of health care that have the potential to present similarly serious health risks such as obesity, chronic disease and more.

Parental involvement in health care situations may make adolescents less likely to disclose certain important pieces of information to their physicians, even though it is necessary for the physicians to provide the best health care possible for their patients.

“When parents get really involved in [their child’s] private lives, they play a major role in influencing all decisions in the child’s world, and they can prevent a child from doing what they really want to do,” junior Gaby Pelayo said. “A student can receive a lot of pressure at home, and they don’t want to get shunned or disowned, so there’s a lot of pressure because a student can get trapped in a situation where it is mandatory to submit to their parent’s choice.”

A 2002 study by Planned Parenthood published in The Journal of the American Medical Association found that “59 percent of female adolescents would stop using health care services, including delaying testing and declining treatment for HIV and STDs, if parental consent were required. Astonishingly, 99% of participants in the survey indicated they would continue to have sex.”

Furthermore, each adolescent’s health care has already been affected by decisions made by parents. Parents choose their child’s physician, which most children have no say in. A good physician is key to understanding and feeling comfortable with one’s health, but adolescents generally do not choose their own doctors.

Dr. Edwin Hui of the University of Hong Kong provides an example of excessive parental control in which a 15-year old referred to as APY had acquired a tumor. The doctors had strongly recommended chemotherapy, but could not proceed without parental consent. Due to APY’s father’s cultural beliefs, the father decided to take APY to his sister, allegedly also a doctor, against APY’s will. APY’s aunt did not offer chemotherapy and APY died from the tumor.

Another instance of controversial parental judgment lies in the example of Christian Scientists, who do not believe in doctors but instead believe in healing through prayer. In 1992, 12-year-old Andrew Wantland developed and died of diabetes within several months, but his Christian Scientist parents neglected medical care for Andrew. Andrew’s treatment instead consisted of prayers from his father, grandmother and a Christian Science practitioner.

[divider]Why parents usually stay involved:[/divider]

From the moment parents see the blue line on their pregnancy test, they are constantly making decisions that affect their child’s health. When the child is but one month old, parents are already deciding whether or how to vaccinate their child. Some vaccinations are mandatory to get into schools, but parents can bypass this for philosophical or religious reasons. According to a recent study by the Center for Disease Control, it was found that since 2006 and to 2015, vaccination rates in 18 to 35 month old infants have decreased by 3 percent.

The legal justification for restricting adolescent medical autonomy lies in the presumption that adolescents lack the maturity necessary to make informed medical choices without their parents’ help.

The current system uses cognitive assessments — or intelligence tests — to determine adolescent maturity. Studies show that on average, individuals become fully capable of understanding medical conditions and their consequences by the age of 14.

Legislature tends to overlook this, assuming that adolescents do not understand their medical rights or realize the importance of their actions. However, there are still a few flaws in that system as it is incredibly difficult for physicians and the legal system to determine the threshold for when an adolescent can appropriately consent to health care treatments without parental supervision.

“The problem is that some of the standard capacity assessments that they use are really just cognitive assessments,” Director of Stanford Center for Biomedical Ethics David Magnus said. “There’s an emerging literature on the developing brain that shows that even if [adolescents] have the cognitive capacity, it may not be the dominant operant module of the brain that is guiding the decision-making process. Adolescents might have emotional centers that swamp cognitive centers, and the developmental process may not really finish until about 25 years of age.”

Parents have a lot of control over their children’s health care because teenagers are known for giving into peer and familial pressure, since adolescents are still figuring out who they are. This leads to greater risks of rash or uninformed decisions regarding their health.

Additionally, health care providers encourage parental involvement. Palo Alto High School Adolescent Counseling Services (ACS) Site Coordinator Kelly Sumner explains that it is important to acknowledge the benefits of parental involvement in decision-making.

“We try as much as possible to involve parents,” Sumner said. “If parents are a positive resource for the student, [they] should not be overlooked. It can be overlooked, and sometimes therapeutic programs for adolescents veer a little too much on that ‘don’t involve parents’ attitude.”

However, there are several reasons why parents should have the right to control over their child’s health treatment. Not only do parents pay for their child’s medical care, they influence in all major decisions is an intrinsic aspect of the parent-child relationship.

Also, many insurance policies detail that major portions of the child’s health visits to be disclosed to parents. Some children give complete control to and respect their parents immensely, which is not wrong in itself, as most parents simply want what is best for their kids. However, they may use their own views as context in decision-making, and for that reason, parental involvement is not a universal benefit.

“Judging confidentiality and the fairness of consent issues should be done on a case-by-case basis,” senior Siddharth Srinivasan said. “A lot of the final decision depends on the child’s relationship with [his or her] parents.”

[divider]Maturity and safety:[/divider]

There is only one way for adolescents to bypass all parental control — testifying and proving in a court of law that they are a “mature minor.” This removal of parental control is only given under extenuating circumstances, which primarily include physical abuse, mental illness of parents and neglect, in addition to a high level maturity demonstrated by the minor. Essentially, when the parents are not abusive, mentally sound and the child is not being physically harmed, there is no legal way to remove parental control.

Medical decisions regarding birth control, hormone regulation and sexual activity are the most apparent instances of parental influence. Some parents have strong feelings on the subject of pregnancy, and sexual health. It is often difficult for a child to approach the parent and discuss matters such as these if she does not feel safe or heard.

The respect for autonomy is reason for health care providers to look for ways to maintain confidentiality between patients and doctors. In general, doctors and therapists want to respect confidentiality as much as possible, although the status quo limits it.

“We wouldn’t [break confidentiality] unless there’s a safety concern involved,” Sumner said.

It is difficult to define that safety threshold, especially because it requires foresight rather than a judgment about the child’s past experiences. Ultimately, it is up to physicians to determine whether patients are at risk of imminent harm.

In particular, Sumner cited an example in which breaking confidentiality was necessary for the well-being of the individual and community. The individual had met with ACS multiple times before the individual’s parents became involved, but Sumner and the ACS team felt that the individual presented a significant safety concern after several meetings, and decided to involve not only the parents but also a county clinician, thus breaking the patient’s complete confidentiality. Sumner believes that ACS made the right decision in doing so.

“I think it went relatively well — the outcome was positive,” Sumner said. “The student is in a much better place at this time.”

Determining a situation of imminent harm is difficult to evaluate, and it would be nearly impossible to construct laws that are able to cover every single scenario.

“Permitting adolescent autonomy has to be done on a case-by-case basis,” Magnus said. “We have laws in place in these different domains, but even with these laws, they give a lot of discretion to physicians. Every case is different — it matters what the burden-benefit ratio is in the decision, it matters whether or not parents being involved is beneficial, it depends on how crucial it is for the adolescent to get treatment. You have to have assessments of the maturity of the particular patient, and you have to have assessments of the circumstances.”

[divider]A look into the future:[/divider]

In California, recent confidentiality laws have been in support of greater adolescent autonomy. Even with legal inconsistencies across the 50 states, the adolescent health care system is looking for the best way to respect autonomy without sacrificing safety.

“In an ideal world, parents would be involved,” Hamade said. “But I definitely respect and understand kids who can’t do that because there are parents who are not very open-minded and protection of the child is more important than parental consent at the end of the day.”

Health care systems have been trying to find other ways to adequately inform and guide adolescent decision-making to protect adolescents from harm. A shared decision-making model, in which a patient works collaboratively with both the physician and his or her parents to find treatments that all parties assent to, has been recommended.

However, it often proves difficult for three parties to come to an agreement on a treatment option, so a perfectly shared decision rarely actually occurs.

“Shared decision-making in practice doesn’t happen for anybody, period,” Magnus said. “If you look at the empirical data based on recorded conversations, the elements of shared decision-making were met less than 9 percent of the time. Other studies show 0 percent. It’s an ideal process, but it almost never happens that way.”

Shared decision-making requires all parties to be completely educated of the situation and the consequences of each alternative action so that they can make informed decisions, but rarely are individuals fully informed about their own health.

“What will happen is that physicians will give the patient incomplete information in ways that are incomprehensible, and then the decision will be what the physician wants,” Magnus said. “These patients are often educated people too, but they have absolutely no idea what’s going on. If you think patients make decisions for themselves most of the time, you are mistaken. Informed assent almost never truly happens.”

Poor communication is the primary detriment to any feasible shared decision-making process. While Magnus believes doctors have the responsibility to inform patients, patients themselves — and especially adolescents — are not entirely honest all of the time in communicating their needs.

“It is absolutely the burden and duty of health care providers to simplify explanations of treatments so that patients are more informed when making decisions,” Magnus said. “But [patients] are often embarrassed to tell doctors certain facts, which are what they really need to know to run all the right tests.”

The solution to that problem may be to facilitate confidential discussions between the adolescent and patient. Physicians must judge based on instinct whether an adolescent is being entirely honest.

“How doctors should be acting is all based on the circumstances at hand,” Srinivasan said. “The child’s health interests should definitely be the primary goal of any health care system.”