Tucked away along a fence lining a rarely used Union Pacific railroad track in Redwood City, a dozen tents and makeshift shelters blend into the trees.

Named by those who reside there, Camp Seaport and other homeless communities have become increasingly common in the Bay Area.

The disparity between the wealthy and poor along the Peninsula is significant. Despite boasting an average income double that of the rest of the nation, according to Business Insider, the Peninsula has the third largest homeless population in the country, as reported by the Bay Area Council Economic Institute.

“California is both America’s richest state, and its poorest,” Gov. Gavin Newsom told The Campanile when he spoke to the class in February 2019.

Contrary to popular belief, the causes of homelessness are not always rooted in substance abuse. Rather, the reasons for homelessness are much more diverse – a variety of life-changing events could propel one to the streets. At the same time, the generosity of others can help relieve such hardships and divert the path of those who may slip into homelessness.

According to Camp Seaport resident Elizabeth Melendex-Wank, homelessness is often brought on by a major life event such as the passing of a loved one.

“People say homelessness is (caused by the use) of a lot of drugs, that everyone uses needles and it’s not true,” Melendez-Wank said. “There are a lot of mental health problems out here. Some people have been here a lot longer and tend to try to cope with everything (using) drugs or alcohol.”

Melendez-Wank said her husband passed away in 2008. After that, she was laid off due to budget cuts and spent five years unemployed, living on $1,400 a month.

Then, her father, who had been battling cancer, passed away.

“Something told me I had to go see my father, so on June 5, 2012, I got a plane ticket and went over (to New York),” Melendez-Wank said. “I became homeless after I used my last paycheck to go to my dad.”

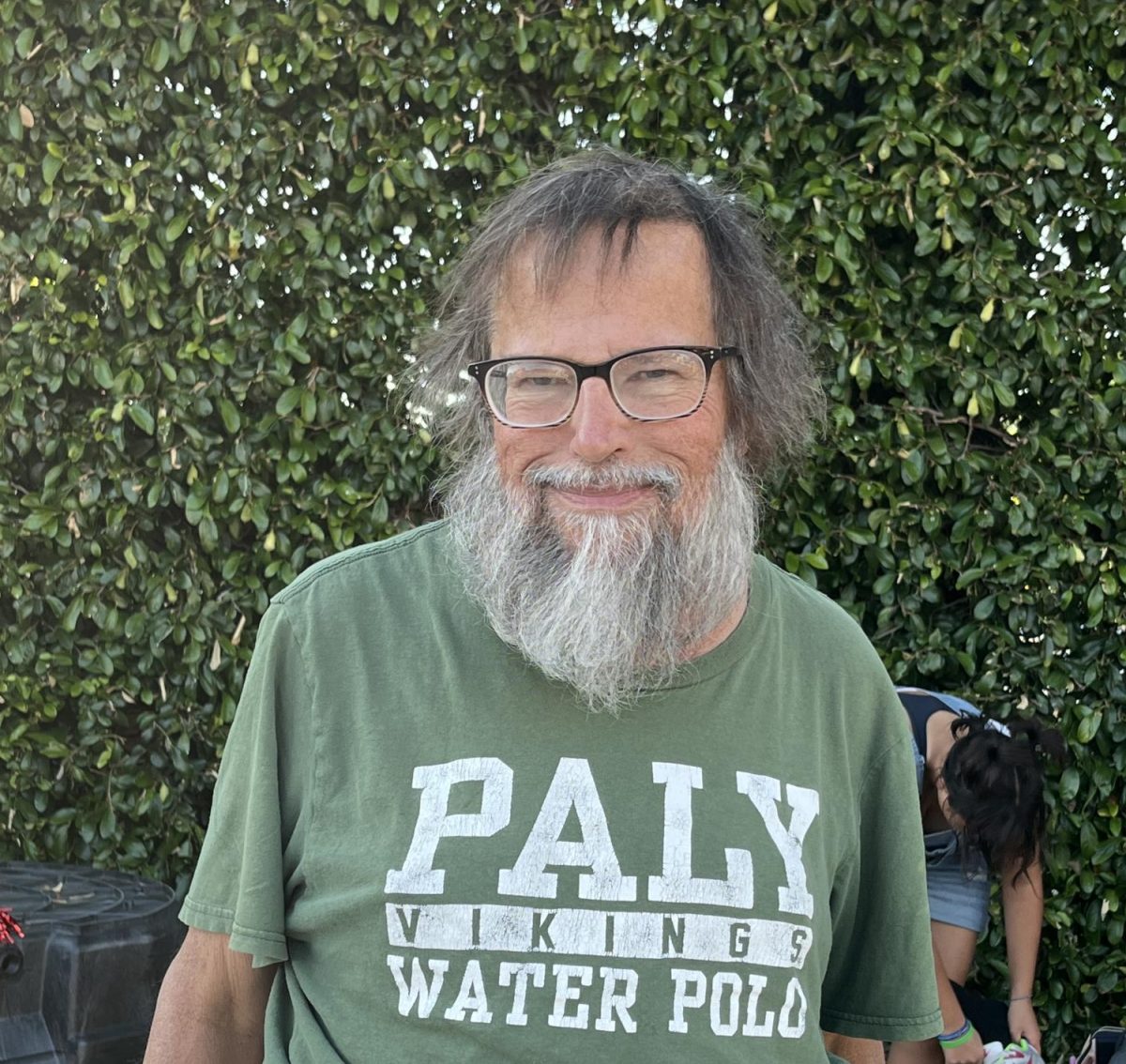

Paly alumni Mark-Steven Holys, who graduated in 1976 and was recently interviewed by The New York Times about how he became homeless, also attributes his homelessness to a family crisis, which he said he did not want to go into detail about.

This crisis, he said, led him to drug use and consequent prison time, which made him unemployable, and eventually homeless.

“(Homelessness) is a combination of a lifestyle problem and heavy-duty life problems outside of that,” Holys said. “I was totally crippled.”

According to Melendez-Wank, who received a masters in psychology, people from all walks of life can become homeless.

“(People) have to understand that we are them,” Holys said. “If we are in this area, we were possibly your neighbor, the people who lived down the street from you last year. Do not think we are different because we are out there.”

Holys’ daughter, Julia Morrison, grew up in foster care and said her current success is due to the empathy her community showed her when she faced difficult times during her childhood.

Morrison went to Greene Middle School and now attends the School of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California.

“I truly believe that we can’t be successful without bringing other people with us,” Morrison said. “I wouldn’t be anywhere if it weren’t for, like I said, PAUSD (Palo Alto Unified School District).”

While attending Greene Middle School, Morrison’s grandmother, who had been taking care of her and her brother, passed away. Because her passing came around Christmas time, Greene Middle School held a gift drive for Morrison and her brother.

“(PAUSD) put us in special programs so we would get extra attention because we started to have behavioral issues,” Morrison said. “(The school was) really attentive to us…I am so grateful for that. I attribute so much of my success to all of the different people along the way who were paying attention.

Morrison contrasts the support she received in her time of need with the current lack of attention given to homeless people.

“When we look at the people living out there in tents and on the street, they’re in a really different situation,” Morrison said. “I was homeless at the age of eleven. I didn’t have anywhere to live — I lived eight places that year. If it wasn’t for all of those people who noticed and cared, I wouldn’t have gotten to where I am today.”

Supporting homeless people through treating them as equal — not less than human — could go a long way toward alleviating the Bay Area homelessness crisis, according to Melendez-Wank.

“There are families that come out and pray and give us bags of food, and the kids say, ‘God bless you,’” Melendez-Wank said. “That’s what’s needed out here because (homeless) people feel disconnected. They only come out at night, and they become antisocial.”

In order for the homeless to reconnect with society, Holys said people need to be more empathetic.

However, according to him, there is a current dehumanization of people who live on the streets.

In many cases, when there is a lack of outside empathy, the homeless develop connections with each other and find motivation through building their own communities.

The people of Camp Seaport have built a tight-knit community, according to Melendez-Wank. They watch out for each other, keep an eye on each other’s tents, take turns collecting water and share a communal kitchen where anyone can use a supply of propane gas to cook.

“What makes me the most happy is cooking,” Melendez-Wank said. “When there are people in the kitchen, there’s no fighting. You enjoy a good home cooked meal, be friendly and communicate. You are grateful that we have what we can get and be grateful for each other. I try to instill that in everybody.”

Melendez-Wank said she is still the same person she’s always been — she’s humble and she cares for people. Her son lives in a camp nearby and visits frequently, however most of her family does not know she is homeless.

Melendez-Wank said she keeps this information a secret from most of her family because she does not want them to feel sorry for her. Beyond that, Melendez-Wank said there is a greater reason for her journey.

“I felt like I needed to do something here — I needed to help,” Melendez-Wank said. “I don’t think my mission was finished. I didn’t say anything because I felt I had something to do here — a mission.”

About a month ago, Melendez-Wank said she received a call from her brother, who lives in Canada, offering her a room in his home.

“My phone wasn’t even working at the time — I think God had something to do with this — he called me and he wants me to go to Canada,” Melendez-Wank said. “He didn’t know I was homeless, he goes, ‘I’m not gonna let my big sister be out there like that.’ He was crying.”

Upon reflecting on their experiences, both Melendez-Wank and Holys have become much more resilient.

Holys said, “The brightest flowers are from the darkest roots.”