With trembling fingers, Gunn senior Edlyn Hsueh clicks “post,” adding to her feed of personal snapshots and portraits, some with her friends and others showcasing revealing costumes.

Almost immediately, her phone lights up with an incoming flood of comments and likes. Little does she know that the scope of her audience spans far wider than the 3,000 regular followers she has on her public account. And while future employers or college admissions officers might be checking her content, Hsueh said she isn’t too worried –– there’s nothing truly inappropriate to trace back to her.

“However, (even though) it depends on what you post, I think you should have the right to privacy for it, if it’s a picture you own,” Hseuh said.

For students looking for a job after high school, going through athletic recruitment, trying to prevent potential legal issues or exploring the college application process, the idea that admissions officers or employers can use what is posted online as part of the admissions or hiring process may seem formidable.

Sabrina Huang, a Stanford PhD candidate in Communications who studies interactions and relationships formed through social media, said people need to be aware of their digital footprint: an online trail that a person creates while using technology.

“Much like a trail of footprints left by muddy shoes, our actions on digital devices such as phones, smartwatches and the internet can be traced back to us, even when we are unintentionally leaving these traces,” Huang said.

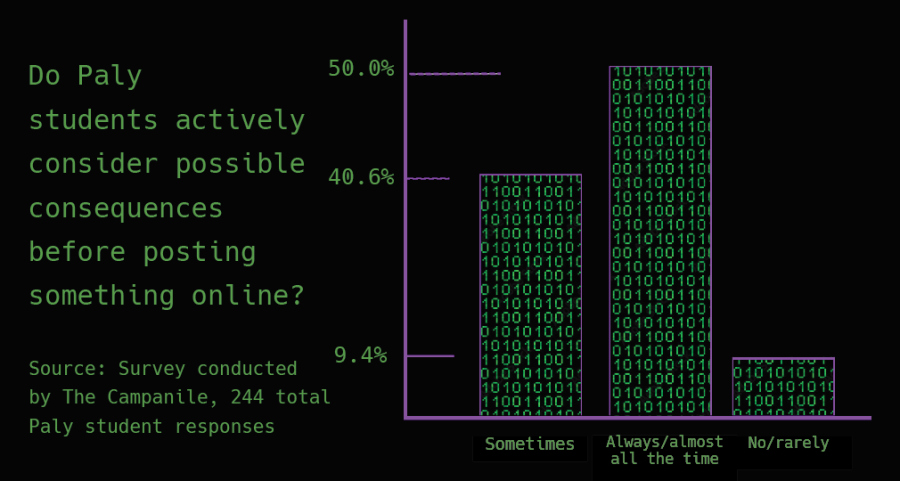

In a recent Schoology survey conducted by The Campanile, 41% of the 245 Paly students who responded said they posted something online and either regretted it or deleted it because they were concerned about the potentially negative consequences.

This regret may be because internet users tend to act more careless on their devices, a psychological concept called deindividuation. Psychology teacher and Teacher Advisor Chris Farina said this concept means a person no longer sees him or herself as an individual who stands out but rather as part of a large group. Teenagers may be inclined to join in on controversial trends or post problematic content as a way to fit in or feel included.

“You lose some of the inhibitions that you would otherwise have, to do things that violate social norms,” Farina said.

Research debunks social media misconceptions

Even though it’s a critical component of online safety, Angela Lee, a doctoral researcher in the Stanford Social Media Lab, said several myths surround a digital footprint’s tangible effects. A digital footprint is often painted as an issue only teenagers have to worry about, but Lee said this is an illusion.

“College students comment on how they can’t believe what kids post in high school, but when I talk with high school students, they can’t believe what their siblings post in elementary school,” she said. “All of us can benefit by bringing a critical eye, no matter how old we are.”

In a 2017 incident at Harvard, the university revoked the acceptance of at least 10 students after officials discovered obscene memes with graphic content targeting minority students circulating in group chats. Not only were the creators of the group chats rescinded from the school, but the people who added to these chats were as well.

Privacy is also an issue related to a person’s digital footprint since technology has the ability to track someone’s every move and boost algorithms that make people want to stay online longer.

But it’s not all bad news. Huang said there’s a common misconception that technology users have no control over their privacy or that privacy doesn’t matter since applications already seem to know everything about their users.

“Fortunately, even small steps, such as updating privacy settings and opting out of trackers can be meaningful in the long run,” she said.

Digital Footprint discussed in Advisory

Farina said that digital tracking issues are taught in Advisory, which is mandatory for all students at Paly. Still, different age groups vary in terms of their knowledge and interest.

The lessons middle schoolers learn about online safety and maintaining a healthy balance between time on and off electronics slowly fade as students transition into a bigger campus with better technology and more use for it.

And Huang said many students aren’t able to control their behavior and understand the fact that they are just a click away from altering their prospective opportunities.

“Teenagers may be especially prone to rash behavior online because their brains — including the part that is in charge of decision-making and thinking about the consequences of actions — are not yet fully developed,” Huang said.

Freshman Lavanya Serohi said she lacks knowledge about her digital footprint because it doesn’t seem to affect her personally.

“I gradually realized that I’m not too worried about college recruiters tracking me because (my posts) aren’t inappropriate, and I have reasoning behind everything I have searched or talked about online,” she said.

However, senior Vienna Lee said she gained experience with digital tracking through exposure to technology at her job and through her social life.

“After working at a technology startup, I’ve learned a lot about … how other brands use other people’s data, so I’ve learned to stop openly sharing things about me on the internet,” Lee said.

Think before you post: online presence can affect admissions

As the digital world grows, college admission officials have adapted to a time where almost every student has an online presence. Computer science teacher Roxanne Lanzot said she notices a change in terms of what colleges are looking for in their students during the internet age.

“I know that a couple of years ago when you were applying to colleges, the college admissions team was not going out and Googling you and checking your Instagram accounts,” Lanzot said.

Because of this change, junior field hockey player Kellyn Scheel, who is looking to continue her athletic career in college, said she is more aware of what she posts online since she began the recruitment process.

“The promotion of anything viewed as intolerable by a given school could ruin someone’s chances at playing a sport there,” Scheel said.

Junior soccer player Rhys Foote said he does not post online at all even though he has social media accounts because he wants any coaches looking to recruit him to see him in a positive light.

“I want to make sure that a search of my name doesn’t take me out of consideration before I even know I’m in consideration,” Foote said.

Though most potential college athletes like Scheel and Foote say they are aware of what they post online. Lanzot said all students should be aware of their digital footprint because colleges may begin to look at applicants’ online posts to thoroughly understand who they are admitting.

“The responsibility shifted to the college admissions team to figure out who this applicant really is,” Lanzot said. “Are they who they say they are?”

And Farina said if what is being posted online is public, a college will look.

“They will scrape whatever they can to try and help them make decisions and find some sort of justification for if they should let this person in or not,” Farina said. “So, if stuff is public, then they’re going to take a look because it helps them learn something about their potential as students.”

Nonetheless, Scheel said posting on social media can also have its advantages in the college recruitment process.

“Social media can be a great way to showcase the work you’re putting in. Especially for prospective athletes, it is important to present your best self on and off the field so coaches know you are serious about your decision to play,” she said. “I myself have an account on Instagram where I only post field hockey-related content. My account is followed by a number of schools which I have connected with as a way for them to watch me grow as a player and keep up with my skill.”

Regardless, Lanzot said she wants students to be mindful about what they post and consider any negative consequences.

“Nothing you post on the internet is ever really erased,” Lanzot said. “So to me, the more pressing message I want students to understand is to really think deeply before you post or comment or put something online.”

Erasure in the EU: protecting privacy or avoiding accountability?

While the discussion on people’s digital footprint within the U.S. may be somewhat convoluted, the European Union has a more clear-cut solution: the right to be forgotten. A 2016 EU regulation states that citizens own their own data and have the right to manipulate and delete their digital information as they wish, as long as it’s not being used for a court case or scientific research. A European court ruling against Google in 2014 further strengthened the validity of the regulation.

Support for this concept has gained traction in the U.S. too. A survey by the Benenson Strategy Group found that nearly nine out of 10 Americans thought that some form of the right to be forgotten was necessary. A 2017 New York bill similar to the EU’s right to be forgotten would have made it mandatory to take down inaccurate or irrelevant statements about someone within 30 days but failed to pass.

While laws like this may champion individual rights and privacy, regulations like this could also give ill-intentioned internet users another shield to hide behind. Senior Mateo Fesslmeier said he doesn’t believe digital posts should be able to be erased so easily.

“Let’s say someone makes a bad decision or does something that’s not right,” Fesslmeier said. “Then they shouldn’t just be able to be like, ‘Oh, can you just take that away?’ or ‘Can you just erase that?’ because that takes away the whole fundamental idea of what they did being not morally correct.”

Farina said he also has concerns related to the enforceability of such laws.

“It sounds nice. In practice, though, how easy is that?” Farina said. “It’s such a pain. I think that it probably makes more sense ultimately to come to terms as a society with the fact that, yeah, everyone will do something stupid and something they may regret.”

Still, for many, the need for personal privacy remains strong, and an engineer at a major social media company, who agreed to an interview only if their name and company were not used, said it’s not a question of if such a law will be passed in the U.S. but when.

“Most of the tech companies are already trying to provide users with a lot more control and transparency about what data is being used and what data is being collected,” he said. “I think it’s a matter of time when it will be implemented in the U.S., and I think it’s going to be sooner than later.”

Digital disparity diverts responsibility

One of the causes of the disparity between people’s online and offline identities is that people are psychologically in a different state when on the internet compared to in real life, Farina said.

“There’s a concept in psychology called deindividuation, which is when you no longer see yourself as an individual that stands out, but rather as a part of a large group,” Farina said. “You lose some of the inhibitions that you would otherwise have to do things that violate social norms.”

Given this difference in psychological states, is it still fair to hold people accountable for their actions? Farina said he thinks so.

“Yeah, of course, as much as but no more than they should be held accountable for if they did that in a real physical space,” he said.

Senior Vienna Lee agrees.

“If you aren’t (held accountable), then you can totally be like, ‘Oh, that’s just me online and not me in person, and I can do whatever I want online, but in person, I’ll just be a perfect person,’” Lee said.

However, sometimes holding others accountable for their actions can be taken to an extreme.

“When I was a teenager in the ‘90s, the internet wasn’t as prevalent, not even close,” Lanzot. “No one had a cell phone in my high school. And so you did stupid things, but there wasn’t a bunch of evidence. There was a picture somewhere floating around, but it wasn’t on the whole internet for the world to see. And then for anyone to download and repost and save forever and republish 20 years later when you’re running for city council.”

In the end, Lanzot said she urges all teens to be more careful when posting on the internet.

“To do stupid things, it’s part of the fun of being a teenager,” Lanzot said. “But maybe it doesn’t need to be shared, posted or published with anyone. Maybe it could just be a private memory with the humans you’re with at that moment.”