Is using standardized testing an sensible practice?

No

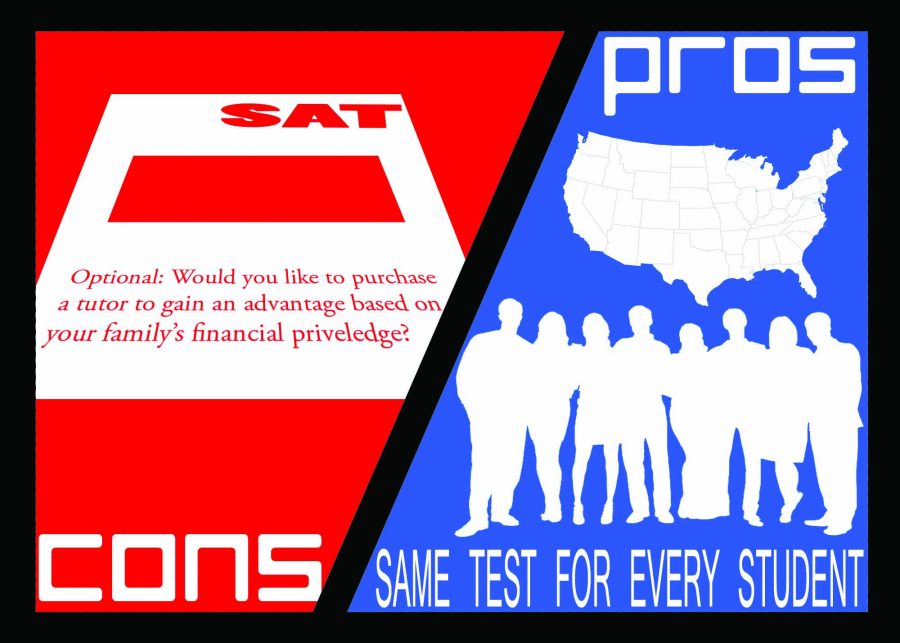

Every year, hundreds of thousands of high school seniors apply to college through an increasingly selective process. In order to gain acceptance into the most prestigious colleges, students must demonstrate strong academic and extracurricular achievement and perform well on the SAT or ACT. In theory, standardized college assessments make sense: they are meant to help admissions officers fairly compare cross sections of students who attend vastly different high schools. Unfortunately, the reality is something quite different.

Affluent students have financial advantages that enable them to outperform students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. By spending thousands of dollars on tutors and test retakes, wealthier students are able to master standardized tests and score in the top deciles. However, families from poorer backgrounds are put at a disadvantage. In addition, standardized tests do not necessarily test knowledge acquired through school due to question biases that may advantage students who have experiences only the wealthy can afford. The SAT and ACT cannot be fair because wealthier families have the means to help their children inflate their scores.

For all tests, studying and practice are necessary to earn good scores and the same goes for standardized tests. However, in school, students are taught the same material by the same teacher, giving everyone a fair opportunity to perform well. In contrast, students taking the SAT or ACT are not all offered an equal opportunity. Many privileged students use tutors. In an affluent community like Palo Alto, an 18-hour Stanley Kaplan group class costs $699 and private SAT tutors charge between $100 and $125 per hour. Wealthy parents are willing and able to spend $1,000 to $2,000 for their child to prepare for the test. Additionally, there is the cost of the test itself. Some students take both the SAT and ACT to determine which one suits them better and then retake the test multiple times to improve their scores on individual sections for a better overall Super Score. At $50 a try, this can quickly add up, bringing the potential investment for preparation and tests to $2,200 or more. Clearly, families earning the median household income of $51,371 (2012 Census Bureau) could never afford to spend almost four percent of their salary on their child’s standardized tests. Students from lower income families are at a disadvantage because they are unable to afford tutoring and multiple retakes. This fact is blatantly obvious through information provided by the College Board, which shows that on average, SAT scores increase by forty points for every extra $20,000 a family makes.

Another issue with standardized tests is that its goal is to test the knowledge of its takers based on what they have been taught in high school. However, the test often draws on information that students may have learned through outside experiences. For example, many questions in both the reading and writing portions of the test relate to international topics. My ACT included an excerpt on Machu Picchu. Fortunately, I had traveled to Peru the previous summer and already knew about the Incas, so I breezed through the questions. This highlights my point: students who come from wealthy backgrounds are more likely to have experiences written about on the SAT as opposed to poorer student who may not have the same opportunities. While the questions can be answered by solely reading the material, a student who has experienced the same thing as a character in a passage will have an advantage over others taking the test. There is an obvious issue here that adds to the unfairness of standardized tests.

Ironically, while the SAT and ACT are supposed to directly correlate with a student’s future college grades, studies conducted by Bates College and the University of California challenge this assumption. Both schools found insignificant differences in first-year grades between students who scored well on standardized tests and students who did not. These studies also demonstrated that, students who achieved high GPAs through high school achieved better grades in colleges. The findings at Bates and the University of California suggest that even if standardized tests do not give wealthier students an advantage, they are still unlikely predictors of college success. Colleges should consider deemphasizing or eliminating standardized tests as selection criteria because of the advantages that wealthier students have to score well and the tests inability to accurately predict incoming college students’ abilities.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Palo Alto High School's newspaper