At the end of every quarter, grade reports are mailed out, dropping into the mailboxes of all Palo Alto High School students. Listed on these reports includes a series of letters; A, B, C, D or F, along with additional pluses or minuses to further differentiate the grades. These seemingly simple letters stand for a straight-forward scale of student achievement; A representing outstanding achievement, C indicating average achievement and F meaning failure of the course. However, the definition of these letter grades has experienced a serious shift in value. Now, many view receiving a C in any class as unacceptable.

A phrase heard around campus all too often sounds something like “Oh my God, I’m failing the class.” But with further inquiry, the meaning of “failing” often means a student is oscillating between a B and C, or even an A and B.

In the high school environment today, many students believe that there is a fundamental expectation that getting A’s is no long an “outstanding” achievement, but rather a satisfactory one, similar to the actual meaning behind a B grade. If the A is the new B, and a B is the new C, what does this mean for the truly exemplary kids who can no longer receive recognition for their achievement? Or, does this just mean we — as a collective generation of students — have grown exponentially more outstanding?

David Brooks, op-ed columnist for the New York Times, seems to think a change in academic rigor is at fault. In one of his more recent articles entitled “The Streamlined Life,” he claims that according to surveys conducted by researchers from UCLA, “high school has gotten a bit easier.”

“In 1966, only about 19 percent of high school students graduated with an A or A- average,” Brooks said. “By 2013, 53 percent of students graduated with that average.”

As well-intended and well-researched Brooks might be, many agree that the idea of high school getting progressively easier over the years is blatantly incorrect.

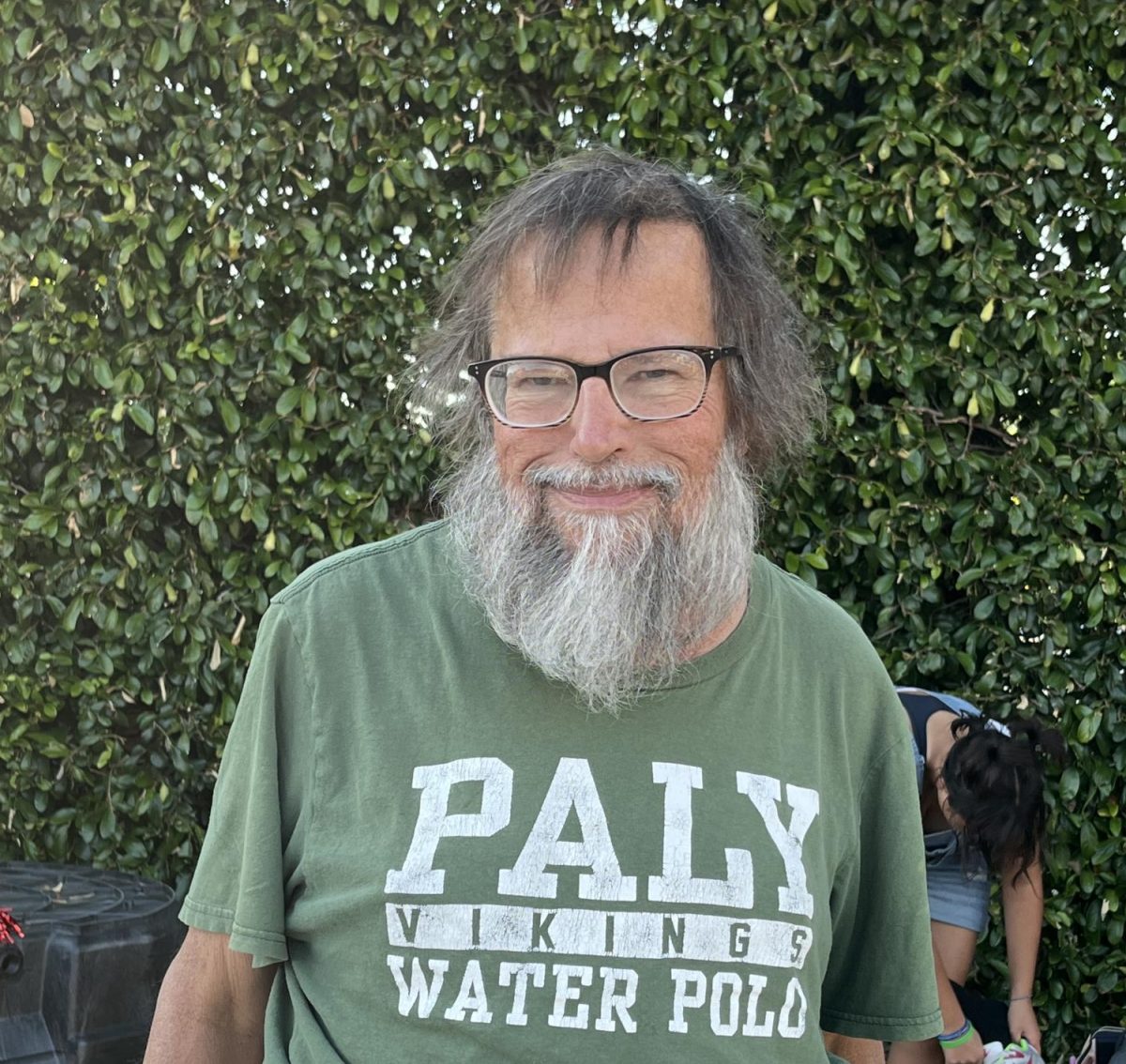

“I see students that are working way harder and doing a lot more outside of school just to make sure that they are successful in the classroom,” Principal Kim Diorio said.

Economics teacher Eric Bloom agrees that student work ethic has increased.

“[Before, there was] no parent help, no tutors,” Bloom said. “[The] percentage of kids who worked as hard as they do now was so miniscule.”

These statistics might have less to do with the difficulty level of high school education, or even a possible increase in overall intelligence in secondary education students. Rather, these rising grades could be more closely linked to a constant problem plaguing the American education system: grade inflation. According to ACT, Inc., grade inflation is “defined as an increase in students’ grades without an accompanying increase in their academic achievement.”

ACT Inc., an achievement-based testing organization, carried out a study of student grade point averages (GPAs) and their correlation with ACT scores over an extended period of 13 years. In the period of time between 1991 and 2003, the study found that students in 2003 had, on average, GPAs that were 0.25 percent higher than students with the same ACT scores in 1991. This significant increase over time indicates that there is a distinct skew in the grading scale of high school students, which can be attributed to several different factors. When examining the rising GPAs of students who take the ACT, the organization identified a divergence in the usage of grades between high school teachers.

“[A] complicating factor is variability in the pedagogical purposes behind the grades teachers may give,” the ACT article said. “For example, some teachers may use grades not solely as a method of rating student achievement, but also as a method of rewarding student effort.”

High schools are continuing to suffer from grade inflation because many schools experience an increased pressure to maintain rising GPAs. According to Jed Applerouth, founder of Applerouth Tutoring Services, administrations are encouraging inflated grades in order to improve the face value and academic appearance of various high schools.

“Teachers are warned that they could be keeping their kids out of top schools by giving lower grades, particularly if other schools in their competitive cohort are playing the inflationary game,” Applerouth wrote.

Furthermore, there is an increased incentive for students and parents alike to continue demanding this overall inflation of grades. Many colleges and universities are more likely to admit a student with a higher GPA overall, than a student with arguably equal academic merit who simply attends a school that chooses to fend off the grade inflation trend.

“Admissions officers no longer have the time to fully differentiate the grading cultures between different high schools,” Applerouth wrote. “Unless admissions officers understand the nuances of grading norms at each school, students from more challenging grading cultures will be penalized.”

An article by Scott Jaschik from Inside Higher Ed offers further analysis behind a recent study involving admissions officers for MBA programs and fake applicant portfolios. The intention was to figure out whether officers would take into account the discrepancies between different colleges’ grading tendencies, and the results indicated that on average, officers admitted more students based off of face value GPA, and more often disregarded students from tougher grading environments.

“When comparing comparably qualified applicants, it was better to have earned high grades at a college where that was relatively easy to do than to have earned less high grades at institutions with tougher grading,” Jaschik said. “Applicants at colleges with grade inflation are winning more than their share of slots, in other words.”

This trend isn’t necessarily uncommon, but rather can be attributed to the fundamental attribution error, where humans tend to place greater emphasis on what they can easily access and view, and tend to undervalue the situation or context when making a judgement. However, recognizing this inherent quality in a mankind’s judgement process might indicate a substantial need for some level of grade standardization and ending the inflation trend.

Grade inflation may be plaguing the nation, but the trend is not one to infiltrate Paly, at least not in the technical sense. According to Diorio, had inflation ever been a serious problem on campus, it would have been reflected in two standards of measure the district uses to determine the school’s success: A-G requirements and the D and F list. A-G requirements are the minimum requirements for applicants looking into UC/CSU’s, while the D and F list is an updated list of students receiving failing grades of D or F. Neither of these forms of measure have experienced any change, at least none that Diorio is aware, to constitute either grade inflation or deflation.

With no significant change in the grading scale happening institutionally, the pressure to keep GPAs high falls onto the students instead. And this increasing pressure is warranted.

“I have a suspicion that some schools hand out A’s much more easily,” one teacher, who asked to remain anonymous, said. “The College Board is putting pressure on schools to do it.”

Many students of Paly theoretically could have the same academic capabilities as students from other schools, but will still have lower GPAs overall in comparison to high schools who succumb to grade inflation. This, unfortunately, puts Paly students at a disadvantage when it comes to the college admission process.

“Colleges are scrutinizing the academic records of students much more than ever before,” Diorio said. “For them, GPA has become very important as they try to weed through so many applicants. When you have a hyper-college admissions environment, it trickles down into the high schools.”

In light of this inequity that imbalanced grading causes, Diorio emphasizes that the only way for Paly to continue thriving in a culture of inflated grades is through maintaining the prestige of the school in the eyes of admissions officers.

“[Admissions officers] pick up things from the newspaper or prior applicants,” Diorio said. “The world needs to know that this is an amazing school. [That’s why with] Star Testing and CST or Smarter Balance next year, it’s really important that everyone takes the tests. Because when everyone takes the test and we get the measure, we do well and that gets out there in the community.”

The consistency in raising the grade averages comes more from outside sources, other than a fundamental inflation. According to the anonymous teacher, the pressure to get A’s in as many classes as possible is perpetuated by a growing fear among the community.

“I think the pressure coming from parents, colleges and the feeling like a B is going to kill my kid,” an anonymous teacher said. “I really feel like the pressure is coming from fear, and fear that our kids won’t get the foothold in our economy. I think there’s just a feeling that every A is a step closer to more opportunities.”

Despite this growing sentiment, the skills that Paly students acquire outweigh the benefits of inflated grades, especially when it comes to college readiness.

“You leave Paly and we kinda kick your butt and you hate uss for it, but you sail through those entry level exams and you’re at the top of your class and that’s what a lot of our old students are telling us,” the anonymous teacher said.