Nearly a hundred years ago, it was considered an accomplishment for students to finish eighth grade, as many jobs did not require a high school or college education. Although people were not expected to complete a higher education, Palo Alto’s foundation as a college town for Stanford University enabled local parents to form their own school district, giving way to our very own Palo Alto Senior High School.

From its beginning, Paly’s strong educational values enabled it to be the ideal location for progressive extracurriculars such as journalism. In the fall of 1918, Paly senior and Commissioner of Literary Activities Dorothy Nichols proposed the creation of a newspaper “by and for the students of the Palo Alto Union High School,” as stated in the 1919 yearbook.

Paly’s journalism program consisted of mostly “pamphlet” style publications such as The Red and Green, Sphinx and Madrono.

“The Madrono pamphlet was a mixed bag of journalism as you will see if you look over the early issues: part news, short story, jokes (most of them pretty silly), athletics, dramatics and at the end of the year a sort of yearbook,” said Paly Librarian Rachel Kellerman in an email.

The newspaper was intended to replace Madrono, which was originally published every three weeks, allowing it to become the high school’s official yearbook instead.

Unlike today’s paper, which is composed of nearly 50 students, the staff was only composed of 10 reporters and business and managing editors from all grades, since there was no Beginning Journalism requirement at the time. Prior to their scheduled September debut, The Campanile ran an editorial offering a prize to the student who picked the best name, which would be decided by a majority vote.

“Actually, we manipulated the decision a little; I really wanted the name to be The Campanile, but some people wanted it to be the Red and Green [the school colors at the time]”

Dorothy Nichols

In spite of The Campanile’s hundred years of dedicated journalism, the newspaper’s beginnings were nearly thwarted by a bad case of the flu. Although schools were closed for five weeks, The Campanile’s staff refused to let the epidemic stymie their plans, even when it reached Nichols.

“Meetings were held (masks on and distances kept as per the board of health regulations) and staff members hurried home in the gathering darkness after weary hours of toil, getting ready for that first issue.”

Elizabeth Wallace

Released with a short delay on Nov. 27, 1918, the paper consisted of four pages filled with athletic, dramatic, military and social news, along with two editorials. After moving to the high school’s new location on Embarcadero Road where Paly currently resides, the newspaper staff secured a couple of tables and a much-needed typewriter for their new office in the Campanile Tower.

“These tables soon took on a very businesslike air and became covered with clippings and papers of all sort,” Wallace wrote. “Not long ago one of the tables disappeared and in its place was found a desk for the editor with plenty of drawers in which to file contributions and communications, as well as to establish a full-fledged ‘morgue.’”

When Nichols was on staff, Paly students had to pay a $1 annual subscription fee to read The Campanile. The business managers aggressively advertised in bold-print notices: “360 students, 150 subscribers — what are the other 210 of you going to do about it?”

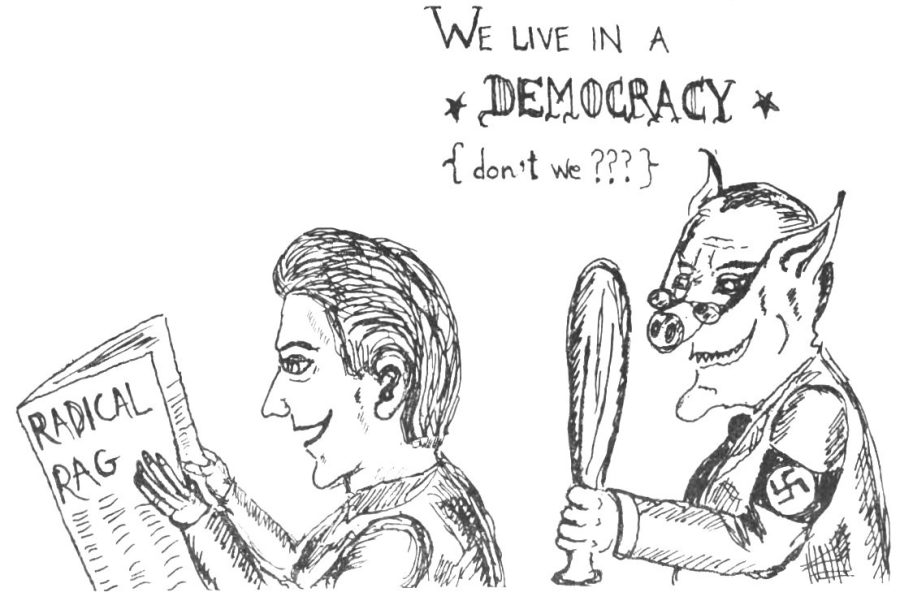

After receiving a few critiques from the many subscribers, an “Open Column” and a “Question Box” were established for the student body; contributions included short stories, poems and a majority of opinion pieces. In addition, according to The Campanile’s semicentennial exclusive, staff writers had the advantage of conducting the occasional eavesdrop for more credible sources as their office was located directly above the staff faculty meeting room.

When all the stories were turned in after several deadline reminders from the editors, Nichols typed them all up and brought them to the Palo Alto Times to be printed. Then, she hauled the huge rolls of paper home while simultaneously proofreading all the articles. The newspaper did not go completely digital until 1997 when the staff transitioned to digital transfer and launched a website.

“During the old ‘paste up’ we literally glued articles and images onto a backing (like an art project) and physically delivered the resulting poster board to the printer to photograph and print. We were using Adobe Pagemaker software to do layout, but we weren’t fully operating in the modern world.”

Matthew Gunn

Through the past 100 years, the newspaper has endured many changes, including the addition of three sections, Lifestyle, Sports and most recently, Science and Technology, now containing 24 pages of content. Nonetheless, the one component of The Campanile that has never changed is its ability to foster lifelong bonds between its many student writers and editors.

“I found the friendships I developed with those a year older as immensely useful,” Gunn said. “As a junior, talking with seniors helped me navigate the college application process. As a senior, I appreciated the insight on college I got from those same Campanile alums.”