It is difficult to imagine that at Palo Alto High School, home to 10 publications and one of the most well-known high school journalism programs in the country, there was once censorship on students’ right to free speech. Just a few decades ago, however, students were forced to go through the effort of secretly publishing and distributing underground publications to express their opinions freely without the tampering of administration or faculty.

During the late 1980s, the Supreme Court case Hazelwood vs Kuhlmeier preserved the right for public school administrators to refuse to sponsor student speech that was “inconsistent with the shared values of a civilized social order.” This case was presented after high school journalist students felt their right to free speech had been violated due to the censorship of a story on teen pregnancy and divorce.

This case applied to student publications that were not established forums by schools for student expression.

Principals and teachers were able to censor content they believed was inappropriate or did not benefit to the educational environment within the school.

[divider]Radio Free Heaven[/divider]

Radio Free Heaven (RFH), an unsanctioned newspaper, was a known leftist publication at Paly. “Ignorance is the curse of God, knowledge is the wig where-with we fly to Heaven,” quoted the paper in its first issue on Feb. 1, 1968.

It had only four pages and covered controversial topics such as civil rights, drugs and the Vietnam war, according to The Campanile. The paper stated that its goals were “objectivity, diversity, quality and truth.” However, it was illegal to distribute unapproved materials on campus.

According to an article written by The Campanile in 1968, then-principal Ray Ruppel threatened to suspend students who violated this law.

“Rather than being an effort to shock innocent students, this paper was established as a means of expressing our views on vital and timely matters,” wrote RFH.

Between the late 1960s and early 1980s, there were many other underground publications, including Movement Against Student Suspensions, Radical Rag, Power to Students and Solidarity.

“For illegally distributing RFH last Monday, 70 students were nearly suspended, including Paly’s student body president, commissioners, four justices of the student court and yearbook editor. So much pressure has descended upon Principal Ray Ruppel that he cannot allow further illegal distribution on campus without automatic suspension of all students participating.”

The Campanile, March 12, 1968

[divider]O.Y.E.[/divider]

O.Y.E. was an underground newspaper published from October 1991 to January 1992. The publication purposefully did not reveal what the initials stood for. Although the state of California prohibited censorship of student speech, O.Y.E. published material deemed to be illegal by the California Educational Code, and as a result, was labeled underground. The publication, assembled by a staff of loosely associated students, focused on giving an open forum to any anonymous student writer.

Dan Potter, the editor-in-chief and co-founder of O.Y.E, described that the newspaper had a main emphasis on expressing students’ opinions on a wide range of topics, political and otherwise.

“It doesn’t really make sense today in a world of blogs and Internet forums, but back in the early ‘90s we had none of those things,” Potter said in an email. “When we started publishing O.Y.E., about half of high school students were still turning in handwritten papers. It’s plainly obvious from a quick perusal that the publication was never about journalism so much as it was about free expression.”

Articles published within the newspaper ranged from a discussion of Student Council and its ineffectiveness at Paly to students’ opinions on current events at the time, like the “Black Market Operation Bust.” One staff member published an article revealing the intent behind creating O.Y.E.

“It seems educators only want youth to be interested in things like student government and school spirit,” an anonymous writer wrote in a December 1990 issue of O.Y.E. “[They] can’t build an environment where students cannot fully express their opinions and expect them to love this environment as well. The administration comes down hard on forms of student expression they deem to be negative. I’m only asking [administration] to be a little more open-minded and try to see the hypocrisy in what they’ve created, and to give this haven for uncensored, unadulterated student opinion a chance.”

Throughout four semesters, Potter and O.Y.E. staff gained increasing levels of support, as well as increased resistance, from Paly faculty members.

At times, they faced difficulty while working through the production cycle and distribution of the newspaper. Not knowing the backlash and repercussions of running the newspaper was “harrowing,” according to Potter.

By late 1991, school officials’ patience ran out and they threatened to expel Potter if he continued to produce the underground newspaper.

This time of difficulty and uneasiness for O.Y.E. led some staff members to leave, resulting in a partially-blank issue.

Potter eventually stepped down from his position as editor, but continued to advise the remaining staff.

Soon after this incident, however, the paper came to an end.

“It was tough going with a constant fear of retaliation from the school administration,” Potter said. “After publishing two issues in 1992 our little underground coalition fell apart.”

While the legality of O.Y.E. has been debated extensively, I think it is important to ask not only the question “is it legal,” but to ask “should it be legal.” Teachers have accused O.Y.E. of being obscene, but is it really? Of all of the students I have asked, not one of them has been seriously offended by the use of four letter words. Even if these words are offensive to some teachers, O.Y.E. was not written for the teachers, it was written for the students. As Tim Dickinson said, “…[these words’] used in an open forum for student expression is wholly appropriate. What do they think it teaches a student if they spend years telling him how the Constitution protects his rights and his freedoms, and then they nail him for assuming that it applies to himself?

From Dan Potter in The Campanile, Dec. 16, 1991

[divider]Present Day[/divider]

Currently, Paly students no longer feel the need to run underground publications solely to express their views because student press freedoms in California have been securely established.

Pupils of the public schools, including charter schools, shall have the right to exercise freedom of speech and of the press […], except that expression shall be prohibited which is obscene, libelous, or slanderous. Also prohibited shall be material that so incites pupils as to create a clear and present danger of the commission of unlawful acts on school premises or the violation of lawful school regulations, or the substantial disruption of the orderly operation of the school.

California Education Code 48907

In 1977, the state passed Education Code 48907, which counters the later Hazelwood ruling. This code allows for student editors, rather than faculty, to edit content.

“At Paly I’d like to say that we have a lot of press freedom,” said Managing Editor of Verde Magazine Stephanie Lee. “I know people who go to other schools who don’t have any press freedom at all because their principal censors whatever they want to write.”

Since Education Code 48907, Paly journalism has covered many controversial topics such as reproductive rights, women in politics, rape culture and stories about the school administration.

“If we had a school administration who was very controlling of what can and cannot be published, many of these stories would have not made it out to the public, and however [these stories] impacted the community would not have happened,” Lee said. “We’re bringing to light a lot of issues that would not have been talked about if there were no student freedom laws that protected us from administration tampering. All the change that we made through student reporting would not [have happened].”

Lee further expressed that student speech is an important aspect of Paly journalism.

“It’s so important for me to voice my own opinions and thoughts as well as help everyone else who [doesn’t] necessarily have that voice to speak up for them and tell their stories,” Lee said.

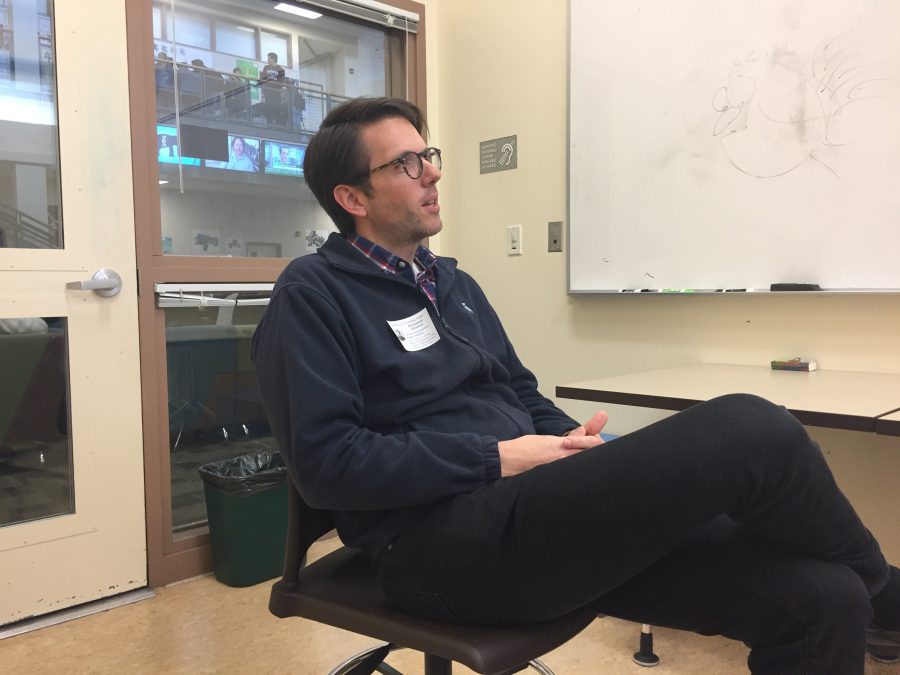

Paul Kandell, journalism advisor of The Paly Voice and Verde, said that journalism at Paly would be significantly different if California had not allowed for student freedom of speech. The administration and faculty would instead have to edit student content.

“[The administration] would slow down the process so much [that] we would become vastly inefficient,” Kandell said.

Pupil editors of official school publications shall be responsible for assigning and editing the news, editorial, and feature content of their publications subject to the limitations of this section.

California Education Code 48907

However, as a journalism teacher, he says he is thankful for his students that this is not the case at Paly.

“Why don’t we have an underground newspaper?” Kandell said. “Because what would they be writing about? You already have the freedom to do everything. I think that’s a good model for a democracy. When you start constraining speech, then you start getting underground publications because people feel like they have to fight or hide to communicate their messages. I’m glad we don’t have that situation here and hope that continues.”